The ubiquitous BSA side-valve! What a proud boast for a basic, primitive design that is seen everywhere and taken very much for granted. The BSA M20 is the more common garden variety BSA side-valve; but how much did the 600 vary from the 500 and just what is it like to ride the much loved, much abused and much respected BSA slogger?

The M21 tested is a product of the immediate post-war motorcycling industry in that it shares the running gear of the war model WM20 despite being a claimed 1947 model. The pre-war appearance is the result of most motorcycle factories producing interim civilian models based on pre-war/war model designs before releasing their new post-war range in late 1947 and 1948.

First though, a history lesson and then we ride the bike. Pleasure must accompany pain, although I’m not sure which process is the most painful. Again I’ll assume that the reader is unfamiliar with the model, please bear with me all of you BSA side-valve fanatics.

First though, a history lesson and then we ride the bike. Pleasure must accompany pain, although I’m not sure which process is the most painful. Again I’ll assume that the reader is unfamiliar with the model, please bear with me all of you BSA side-valve fanatics.

The M21 initially had a bore and stroke of 85mm x 105mm for a swept volume of 595cc. In 1938 it was brought into line with the M20 with a bore of 82mm and a 112mm stroke giving 591cc. A similar bore as the M20 turned the M21 into a long stroke version of the 500 and meant the factory could use common engine parts. The M21 still used heavier flywheels though, to provide the low rev pulling power needed for sidecar work.

The performance of the M21 was claimed to be a solid, pumping 15 BHP, however this did not translate to top speed, with sidecar gearing 50 mph was a less than comfortable maximum. By way of comparison the M20 with solo gearing was good for 13 torquey BHP that guaranteed a good 55-60 mph.

The side valve’s low revs, the long inlet tract, low compression and the poor thermal efficiency of the combustion chamber all contributed to the low power output but then a high top speed wasn’t the intention.

Detail changes to the BSA “M” series were slight before the dreaded “Hun” started the “big one.” The popular M21 side-valve was first produced in 1937 accompanied by a range of “M” series BSA’s. There was the M19 350cc OHV Sports, a solo M20 500cc tourer, the 600cc M21 for sidecar work, the M22 500cc OHV tourer and the M23 “Empire Star”. This bewildering array of models did little to help BSA’s marketing strategies and the company was forced to rationalise its line-up, even if only to help with its spares situation.

The military orders came flooding in. The War Department took every machine the BSA factory could make including M21’s. After the fall of Dunkirk the supply situation was so grim all efforts were concentrated on churning out M20s, despite their clear unsuitability for military use. War is hell and the military was determined that it wouldn’t only be the enemy that suffered. For off-road use the BSA was overweight, had cumbersome handling, precious little ground clearance and was somewhat pedestrian beside the envy generating Matchie G3/L. As a trade-off and I shouldn’t be too harsh, the BSA M20 was well made, reliable and mechanically sound and relatively quiet.

Production of the M20 continued unabated and by the end of the war 126,000 machines had been produced and the factory was making up to 1000 sidevalvers a week. The M21 recommenced production in 1946 basically unchanged from the pre-war model but differing from the WDM20 in that it had a six spring clutch, an enlarged toolbox, sidecar lugs and civilianized valanced mudguards. A winged BSA metal tank badge was fitted to impress potential buyers. In 1948 the M21 gained telescopic front forks and a redesigned front down tube frame. This modification was necessary to accommodate the vastly increased wheel movement. A revised gearbox was fitted during 1949 which accommodated both the speedo drive and an enclosed clutch mechanism. The quick detachable rear wheel was discontinued in the same year much to the relief of those who experienced the wheel detaching itself on the move. Alloy heads with a bronze insert for the plug followed in 1951 in an attempt to correct over heating which could occur through the old iron heads. The alloy heads may have run cooler but they did little for the mechanical quietness of the motor. The increased ringing of the alloy head was very noticeable. Plunger frames were made available as an option in 1951 as well and offered a greater degree of comfort and handling for the rider. The quick detachable rear hub was re-introduced on the plunger frame. In 1955 M20 production came to an end although new or refurbished military models were still being dragged out of the supply stores into the mid sixties.

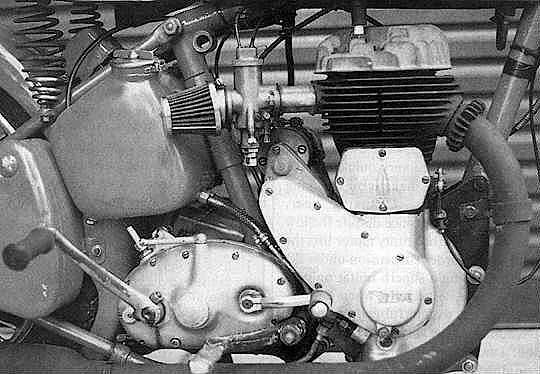

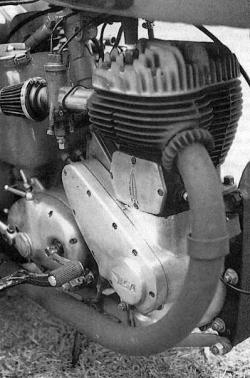

Amal Monobloc carburettors were fitted to the M21 in 1955 offering better breathing and adjustment. A new 8 inch front brake was fitted in 1956 along with a slimmer front mudguard. Various modifications were made to the model to suit the British Automobile Association requirements. The Automobile Association was the last major purchaser of the model. One significant change was a crankshaft mounted alternator to power a two way radio for the Road Service Officers. Production finally ceased in 1963 when sidecar outfits found they could no longer compete with the Leyland Mini. The BSA M21 was no orphan in this regard. Looking at the motor of the test bike, the bike’s pedigree is a little suspect; but then who knows what the factory was willing to export to transport hungry post-war countries like Australia? The engine is stamped YM21 indicating that it is a 1948 600cc model. The licence papers state quite clearly that the bike is a 1947 BSA motorcycle. I guess we can allow the licensing authorities that little mistake? The frame features the later swept-back front down tube also introduced in 1948. This frame was designed to accommodate the new telescopic front forks, yet this bike features the good old BSA girder front fork! The gearbox features an enclosed clutch operating mechanism and the speedo drive. Both features of the 1949 gearbox. The head is the aluminium alloy V-finned item introduced in 1951 and the carburettor is an Amal monobloc from 1955. I guess we can allow this worthwhile modification, especially as the worn out original carbie was produced for inspection. So there we have it, basically a 1948 M21, no longer wearing the original paint job; but it is relatively complete and still wearing all of its extensive chain guard fittings and surprisingly is relatively oil tight

The engine is one huge, very old fashioned cast iron barrel with the timing gear and side valves on the right hand side. A small airway is provided between the barrel and the valve gear. The timing gear consists of separate inlet and exhaust cams driven by the crankcase pinion which in turn drove the magdyno, five gears in total hidden under a timing cover which has the letters BSA cast into it. Above the timing cover is a large plate with the BSA “piled arms” symbol cast into it. This plate when removed enables easy access to the tappets. Looking at the tappets themselves I find that they are designed to rotate to promote even wear. Steel tappet guides are screwed into the crankcase itself (and incidentally the cast iron versions have a habit of fracturing when removed without due care). The exhaust tappet is acted upon by a cable operated decompressor lever and attention should be given to the free operation of this assembly as it has a tendency to stick. Dry sump lubrication imposed a design limitation on the frame that would be unacceptable on the more powerful bikes we have today. Under the timing gear a worm gear driven oil pump required a large bulge in the crankcase. To accommodate this “bulge” the lower frame tube member has a kink in it to clear the casing. Even the Gold Star had to have a kink in its frame for this purpose. The lubrication system is reputed to be very effective and is the oil is filtered by a mesh filter in the oil tank and a gauze screen on the pump.

Riding the beast meant I had to start it. Having been told that BSA side valves were reliable and easy starters I approached this matter confidently. The kick start had an awkward throw and started to function too late to offer a good swing. Not that it mattered much. With all my weight and energy I could hardly move the thing and then only with a tired wheeze from the motor and this is a low compression motor! Using the de-compression lever I almost fully decompressed the motor and pumping away like a two-stroke I managed to get the beast to fire. What a wonderful noise, the engine settled down immediately to a beautiful slow “Ka-chuff, Ka-Chuff, Ka-chuff.” With a little judicial use of the advance/retard lever the engine note deepened and reduced to one stroke a minute, or thereabouts. I was beginning to enjoy that whopping 112 mm stoke after all. When the throttle was opened the front wheel began to agitate, the centre-stand began to migrate the whole bike across the driveway and the rear tail-light began to dance a jig. I began to get the impression that some vibration might exist some where in this machine.

Climbing aboard the sprung saddle I pushed the bike off of its stand and levering the gear lever up into first with an almighty graunch away the bike went. A little attention to the clutch would have given me time to actually use the throttle; however the superb grunt of the motor carried me across the lawn without stalling and gave me time to take control.

First gear was very slow for sidecar work and could be avoided for solo work. Top gear was reached very quickly as the motor’s sheer torque makes gear changing mostly unnecessary Changing gear however is good fun as despite the low power and speed the grunty motor lifts the bike up on its girder suspension under acceleration giving a superb imitation of a powerful bike. Especially as all this is accompanied by a wonderful exhaust beat.

SUGGESTED READING

BSA Pre-unit Singles – Owners Workshop Manual Haynes Publishing

British Motorcycles from 1950: Vol 2 Steve Wilson, PSL

The Story of BSA Motorcycles Bob Holliday, PSL

The Book of the BSA W.C. Haycroft, Pitmans

BSA Motorcycles 1935-40 BMS

The first Classic BSA Scene BMS

The First Military Machine Scene BMS

BSA M20 & M21 Super Profile Owen Wright, Haynes