Around the world with The Bear – Part Seven

The King of Every Kingdom – Around the world on a very small motorcycle

With J. Peter “The Bear” Thoeming

We left our heroes last week as they readied to fly out of Bangkok in Part 6. Will Nepal welcome them with open arms?

Nepal

I enjoy flying with Thai, not only for the free scotch and champagne but also for the friendly cabin crews. We had a relaxing trip and arrived at Tribhuvan Airport in Kathmandu in good shape, where I discovered that I had not only packed my ticket in the pannier but my passport photos as well. The pleasant Immigration man shrugged, waived the requirement of a photo for the Nepalese visa and let me through.

An amiable three-hour wrangle with Customs followed about the bikes. They finally accepted our Carnets and we were free to pick up the machines. ‘Pick up’ was right, too. Our carefully constructed pallets had disintegrated and the bikes were on their sides, Charlie’s leaking acid from the battery.

An amiable three-hour wrangle with Customs followed about the bikes. They finally accepted our Carnets and we were free to pick up the machines. ‘Pick up’ was right, too. Our carefully constructed pallets had disintegrated and the bikes were on their sides, Charlie’s leaking acid from the battery.

A friendly bystander brought us back a gallon of petrol from town and we wobbled off on near-empty tyres looking for a service station. We finally found air at a tyre shop. Service stations don’t stock it in Nepal.

Which reminds me, don’t ever ask for air in Malaysia when you want air. Air means water. So the Malaysian air force is actually the navy. True! Would I lie to you?

Once in Kathmandu, we parked in Freak Street and looked for accommodation where the bikes could be parked off the road. A young Australian woman, a computer programmer turned trekking guide, recommended the Blue Angel. Being Marlene Dietrich fans, we checked in there. It was roomy and clean and had a carport where the bikes could be chained up.

Despite being one of the most unsanitary collections of buildings in the world, Kathmandu is a comfortable, relaxed town. It’s fashionable to think that all places are spoilt in time, but Kathmandu seemed better to me in 1978 than it had in 1970, when I’d last been there: fewer out-and-out derelict hippies, apparently less hard drug usage and a less frenetic street life, but all the little chai bars and restaurants were still playing Dark Side of the Moon.

I introduced Charlie to the peculiar Nepalese idea of European cuisine. We ate things like mashed potatoes with mushroom sauce, buffalo steak, lemon pancakes like citrus-flavoured inner tubes and cast-iron fruit pies. Not as bad as it sounds, actually.

Gives your jaws a workout and it’s bound to be healthy. Restaurants with names like Hungry Eye, New Glory, Krishna’s and Chai ‘n’ Pie still abound. The New Eden reminded me of an exchange I’d listened to in there a few years back:

American voice No. 1, in front of counter: “Ah, how much are the cakes, man?”

American voice No. 2, behind counter: “Chocolate two rupees, banana two rupees, hash one rupee.”

No. 1: “Ah . . . how come the hash cakes are cheaper than banana cakes, man?”

No. 2: “Because hash is cheaper than bananas.”

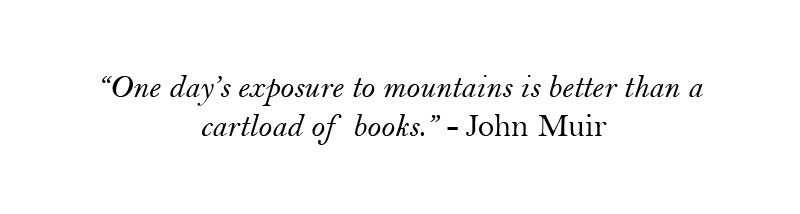

One morning we got up very early to ride out to Nagarkot, a hill station near Kathmandu. We had hoped to get there before the mists rolled in and hid the Himalayas, but I got lost on the way, and all we saw was an enormous wall of cloud with Everest somewhere in the middle. Other daytrips went to Bodnath, the monkey temple; to the giant stupa at Swayambu; and to the river temples at Dashinkali.

We also ‘conquered’ Pulchwoki, a 9050-foot hill behind town, on the bikes, travelling on a 14km dirt road up to the top. Wherever we went in the countryside, the sealed roads were covered in freshly harvested grain sheaves. The locals thresh in the simplest way possible—by letting the traffic run over it.

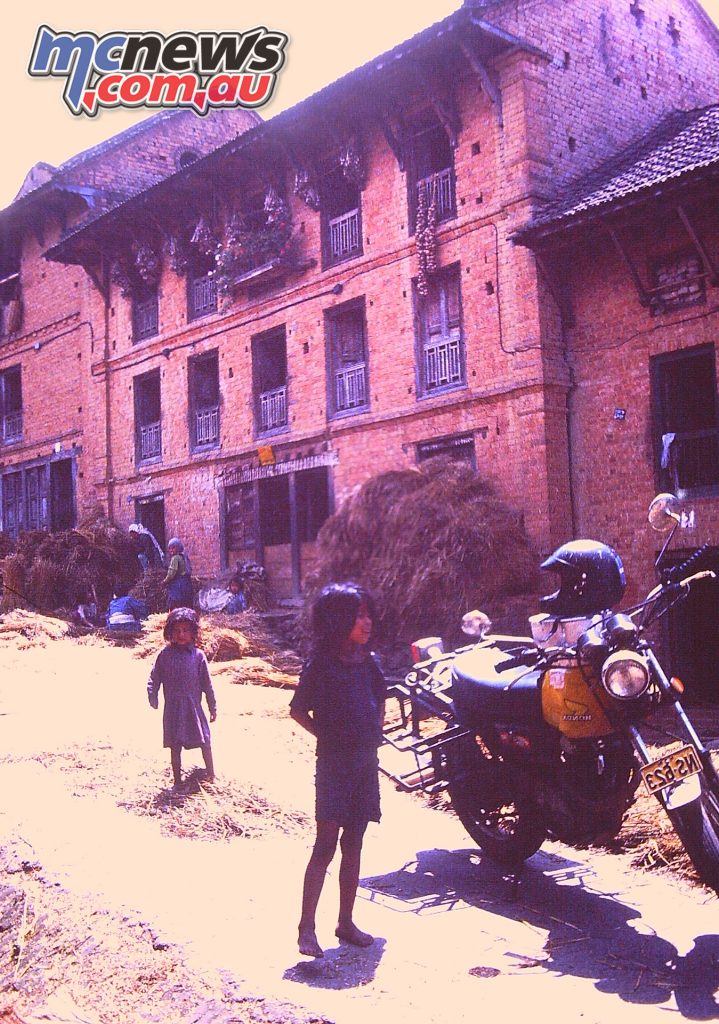

There was a bike shop near the Blue Angel. I peered in one day and was invited to inspect the premises. The tools consisted of a screwdriver and a complete set of shifting spanners.

We secured visa extensions and took off for Pokhara, Nepal’s second city. The road was awful, more potholes than tar, until we passed the turn-off to Birganj and thence India.

After that it improved dramatically and was serviceable even despite the occasional mud slide or washaway. It was built by the Chinese and follows the shoulders of the river valleys over three low passes until it gets to the plateau that holds Pokhara. Charlie went off trekking, walking up in the mountains along the paths that serve the local people as roads.

I checked in at a small, two-storey mud hotel and took it easy, bartering with the Tibetan pedlars, reading and writing. Tibetans are magnificent-looking people, like idealized Red Indians. They also have a great sense of humour. Or seem to, anyway.

I couldn’t understand their jokes, being totally ignorant of Tibetan, but their laughter was nice and inclusive and I never felt as if they were laughing at me. Could have been wrong about that, of course…

Being a little worried about drinking the water, I asked for a glass of boiled water at the hotel. I got it, too. A glass of boiling water—not quite what I’d intended, since I wanted to drink it. After that, I collected water from the roof during the frequent thunderstorms.

The family running the hotel was very kind and kept offering me places in the buffalo stall for the bikes. I didn’t think that was really safe; those buffs might have been good-tempered enough but they were also enormous. The thought of one of them sitting on or leaning against a bike was a bit worrying.

Pokhara itself is a long, narrow town as yet little touched by modernisation. At one end it runs through large mango trees down to Lake Phewa, where the small hotels and shops catering for Europeans are.

My shoulder was finally recovering, even though the torn muscles were still sore, and I just wandered around quietly. There was a lot to photograph, from the farmers arriving at the lakeshore in their dugout canoes to Machupuchare and the Annapurnas lifting their peaks high in the clear morning air.

It’s easier to see the mountains from Pokhara because the town is higher than Kathmandu, although you can’t see Everest, which is too far away.

Charlie returned refreshed by his days in the mountains, and we took to the Siddhartha Highway, heading down to India. Nepalese friends had warned us that the road was ‘not very good’: built by the Indian government, they shrugged.

How right they were. The road is a nightmare of once-tarred dirt and gravel, but the scenery is superb—I think it is, anyway. As we came down through the deep river gorges, I wasn’t often game enough to take my eyes off the road to admire it. Might want to go back there some time, like when I think it’s time to shuffle off this mortal coil.

India

The Nepalese customs man glanced at the souvenirs we’d bought and asked, ‘Where’s the hash?’ with a grin and waved us through. We had donned our safari suits and the Indians were duly impressed; nobody asked for driving licenses, insurance, vaccination cards or anything else except our passports—we were through in minutes.

As we rode along shaded by great mango trees we diced with the traffic as far as Gorakhpur. Indian roads are alive with every kind of human, animal and motor powered transport imaginable. The truck drivers, being Sikhs, are pretty well unbluffable and all else moves too slowly to be worth bluffing.

The Standard Hotel provided a welcome cool room. A gentleman I took to be the owner insisted on buying us breakfast next morning and involved us in a political discussion. It was his theory that Indians are so keen on politics because they can’t afford any other kind of entertainment— politics is free. It also uses relatively few calories.

We passed a funeral on the road that morning, the body wrapped in gold brocade from head to toe—a rather sad display of affluence among the drabness and obvious poverty. But each to his own. If you gotta go, go in gold brocade!

We passed a funeral on the road that morning, the body wrapped in gold brocade from head to toe—a rather sad display of affluence among the drabness and obvious poverty. But each to his own. If you gotta go, go in gold brocade!

In Ghazipur we had intended to change some money, and consequently went looking for the bank. Despite repeated sets of directions, we couldn’t find it. Eventually someone took us right to the door. We’d been past it several times, but there was no indication that it was a bank. It looked like army barracks.

It might just as well have been one, too; they would only accept US dollars, which we didn’t have. Not even Sterling, and this in the land that remembers the Raj so fondly! We revised the name of the town, in our minds at least, to Khazipur and left. “Khazi”, I understand from a British ex-soldier friend, is British Army slang for toilet.

On into the increasingly hot day to Varanasi, where one of the banks had a ‘late branch’ in a hotel. We spotted a sign saying ‘cold beer’ just outside, and Charlie was dispatched to investigate while I changed money. Not much luck for either of us.

The bank clerk tried to give me rupees for $40 instead of the £40 I’d given him and turned quite nasty when I pointed out the ‘slight’ discrepancy, and Charlie discovered that the beer shop hadn’t had an ice delivery for a couple of days and all the beer was warm.

Next installment, discover why tea is not the ideal go-to drink when you can’t get cold beer!