McAMS Yamaha British Superbike R1

230 hp, plus, no traction control, no rider aids – how hard and scary is a British Superbike to ride? We take an exclusive spin on Yamaha’s 2020 R1 Superbike.

By Adam Child ‘Chad’

Photography by Joe Dick

Unlike ASBK, British Superbike machines are fitted with a control ECU and sophisticated traction control systems are not permitted. Yes, that’s right, over 230 hp from the cross-plane inline four-cylinder engine, but with all the sophisticated MotoGP-derived rider aids that come as standard on the 2020 R1 removed for BSB racing.

In fact, many entry-level road bikes have more electronic assistance than this BSB Yamaha R1.

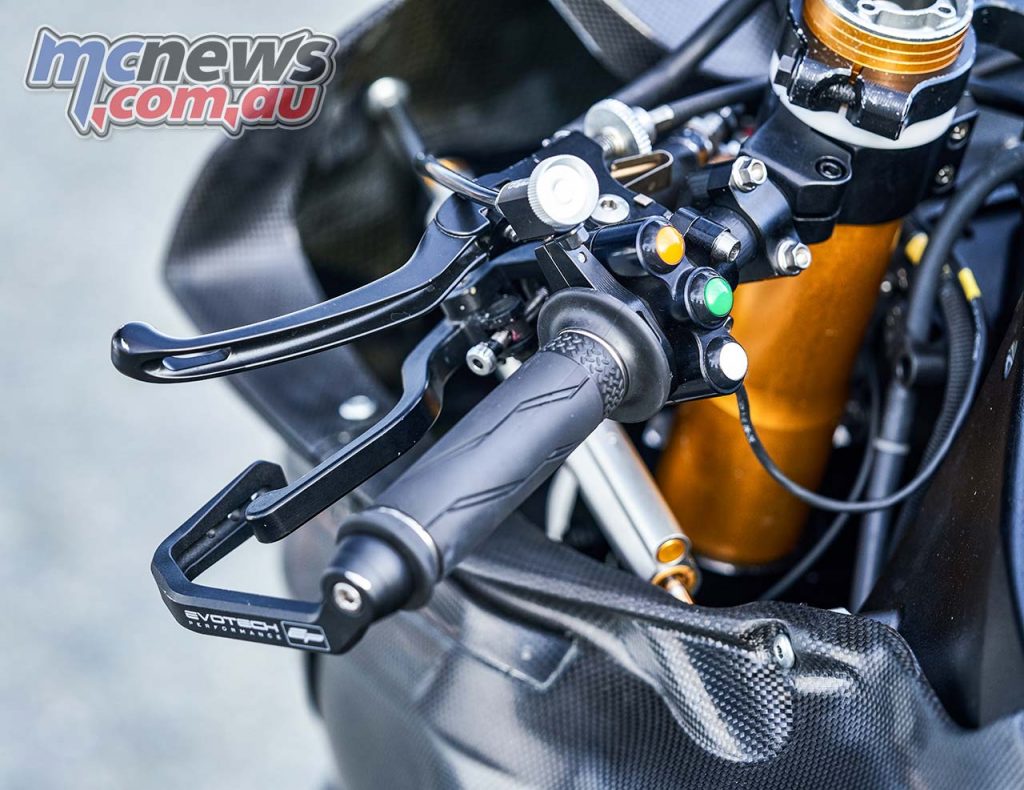

To add to my stress, there are two levers on the left bar: one a clutch lever, facing almost vertically upwards, and a BMX style back brake, where you normally find the clutch. If I grab the back brake by accident, mistaking it as one might for the clutch, a catastrophic crash will follow.

Also, the gearbox is race shift, not road, and the bike is set up for McAMS Yamaha’s ultra-lean racers Englishman Tarran Mackenzie and Australian Jason O’Halloran, not me, a 40-something dad who last went to the gym when lycra was the preserve of heavy-rock bands.

If I wasn’t worried enough, we were only a few weeks away from the season opener (now cancelled, obviously), and nobody except O’Halloran and Mackenzie have ridden this bike.

To get the R1 this far has taken six-months of development, countless hours of dyno time and man hours plus a huge financial commitment.

Steve Rodgers, the team owner, is a relaxed and friendly man but if I crash this R1 I may as well walk into the parched scrubland that surrounds Almeria with a shovel.

Clearly concerned team personnel want me to get sized up and run through the controls. I barely understand the readout on my watch, so the BSB Yam’s cockpit is a daunting view, with three buttons on the left and three on the right. Rain light is green, ignition white, engine brake map orange/yellow; green is pit lane, yellow pump, and another green is go.

Then there are the physical limitations. Tarran uses a bespoke fixed seat, with a backstop that forces him against the tank, which means he can’t move forwards or backward in the seat. He is also the size of a 14-year old boy while I am not. Amusingly, we discover that I can’t fit in his minute seat and I’ll have to use Jason’s, which is a ‘conventional’ flat perch.

We also run through the very alien controls. Once moving you no longer need to use the clutch. The gearbox is clutchless on up and down changes, which explains why the clutch leaver looks so odd. Underneath the clutch is that back-brake lever, which the team call the BMX brake.

There is also a conventional back brake under my right foot. The theory is that one is used to control wheelies, the other is used to stop the bike. It sounds confusing and worrying that’s because it is.

I have two thoughts running through my mind. 1) Don’t look like embarrassingly slow and 2) don’t crash. I have rivers of sweat pouring down my back, and my heart rate is racing already, and I’ve only just put my leathers on.

The McAMS Yamaha starts with an angry snarl, the crossplane R1 must be one of the best sounding bikes in the British Superbike paddock. Crew chief Chris Anderson gives me a push, wheels turning, into first gear, feed the ‘vertical’ clutch out and we’re away. I trickle down the pit lane, tap into second on the race shift and enter the track. I’m holding onto the left bar like a koala on a windy tree and have already decided to just leave the BMX back brake alone.

The first few corners are taken lightly, I don’t want to make any stupid mistakes. But, after a few corners, it quickly becomes apparent the R1 doesn’t feel right. Despite the Spanish sun, the heat isn’t being maintained in the Pirelli slicks, the Ohlins suspension isn’t being used, this BSB bike isn’t happy. The fuelling is incredibly smooth at low revs, there’s virtually no snatchiness; engine wise, you could ride this to the shops, but the rest of the bike is complaining about my pedestrian pace.

Halfway into the lap and it’s time to pick up the pace a little. The noise is more apparent, there is a unique and distinctive bark from the full titanium race system. Between clutchless gear changes the engine momentary cuts the ignition, its split-second backfires are additive as McDonald’s to an obese American. The shifts are smooth and effortless, up or down the revs perfectly matching the back changes.

From lower down in the power, where normal racers would never venture, the throttle response is striking, power is linear, the fuelling is impressive. Towards the end of my first lap, I’m starting to think I might have made a mistake, the angry bull isn’t that scary after all. It’s light, flickable and easy to manage. Then we hit the back straight and everything goes mental. For the first time, it’s full throttle. As fast as I can tap the gears it keeps accelerating and wanting more – second, third, fourth, fifth, and as fast as that and the long 900m Almeria straight is done. It doesn’t feel barking fast, but the café/restaurant at the end of the straight is appearing alarmingly quickly, time to brake.

Back through the gears as fast as my dancing feet will allow, remembering there’s no need to use the clutch, just jump on the front brake, and leave the back brakes alone, oh yeah and no ABS. My brain can only deal with one thing at a time, and it wants the world to stop moving so fast! The Brembo stoppers are incredible, my eyeballs nearly hit my visor, my arms are hurting already. It feels like I’m about to flop onto the dummy petrol tank. But, there’s no need to brake so hard, I’ve braked way too early, my brain hasn’t recalibrated to BSB performance.

Into the chicane. Right, then flick left past the pit-wall, second gear, tap into third, try not to look too slow in front of the McAMS Yamaha team. Again, into turn one, the downhill right, and the brakes are stronger than my arms. I knew the engine performance would blow me away, but I wasn’t expecting the same from the front end. Turn four’s long left-hander, with a late apex, is confidence-inspiring, knee down, great feedback and immense grip. But unlike the road-going bikes I’ve ridden previously here my toes aren’t dragging, despite the decent amount of lean. I’m unsure of how far I can actually go? It’s a strange feeling, one I’m not used to. On a road R1, on-road rubber you soon find the limit, but the BSB Yamaha is another level.

The steering is super-accurate, I’m feeling more confident, getting closer to the apex. The fast approach to the final chicane, and it’s point-point accurate, even with a heavy-breathing club racer at the helm. The R1 rides over the kerbs as if by magic, and after a short handful of gas I’m ready for the straight again.

Strangely it doesn’t feel mentally quick on the straight as the track is wide and there are no peaks in the power. Yes, it’s fast, with 230bhp plus, but I’m not clambering over the fuel tank to keep the front wheel down. I’ve ridden bikes with less power that feel quicker. The McAMS bike just accelerates effortlessly. Twist the throttle, tuck in behind the new aerodynamic bodywork and tap the gears when you see the gear shift indicator lights illuminate. You don’t really get a sense of speed until you see the end of the straight appearing at a scary rate. Then it’s time for more arm torture.

As I cross the line once more my lap time appears on the Motec dash, and it’s embarrassing. I’m battered already, like a boxer on the ropes. Sure, my confidence is building but I just don’t have the skill or bravery to throw it on its side to elbow-down levels of lean. I’ve shown off and dragged my elbows for photos many times previously, but this is very different, this is race pace, all be it my race pace. The grip and feedback are there, the bike is capable of more, but it’s like walking on the moon for the first time; I’m in an unknown area, past where normal bikes would start to complain or drag toe sliders.

My ‘fast’ lap starts to come together. I have a smooth run through the blind right-hander (turn 5 to 6) and the faster sections are clicking together. I get a lovely drive towards the final chicane, grab third gear, and the drive is smooth and stable. Again, I’m not fighting the bars, just accelerating rapidly. Braking and turning, trying to scrub off speed, and there isn’t any sign of understeer. As I come onto the back straight once more, I sacrifice entry speed to get a good exit and only change gear when all the rev light illuminates. For the first time I manage to grab sixth gear on the long straight and despite grabbing top gear the R1’s still accelerating as hard as it was in third.

Over the line, 1minute 50 seconds, not bad, though I’ve gone quicker on road bikes, so I push for one more quick lap. As I brake into turn one and my arms scream, they simply aren’t willing to go one more round. I’m flapping and holding into the ropes. It’s time to do what I do best, look fast for photographs and stop worrying about lap times.

The R1 is incredible, and I’m only at 50 per cent of what the bike is capable of. I’m a different size and weight to the riders, I’m not using all the suspension to the full effect and in some corners I’m a gear lower than I should be – I can only imagine how good this would be perfectly set up for my weight, speed, and style.

After a few more laps it’s time to come in. I’ve ridden race bikes before – WSBK, GP and TT bikes – and I’ve been professionally testing bikes for 20 years, but I didn’t expect the BSB bike to be so physical, especially on the brakes, and, honestly, I’m only tickling it. How do they do this for than half an hour, twice in one day in a race weekend? It’s beyond belief. On top of that, they are changing mappings, controlling rear tyre life, reading pit boards, working on a race strategy, and bashing fairings with another 30 skilled riders all hungry for the win. I had the greatest respect for BSB riders, from the ones at the front to the guy or girl at the back, but now it’s ten-fold.