Six hours a year… By Phil Hall

For reasons beyond my control I yet again have totally failed to get to the State Recreation Area at Broadford, Victoria for the annual Penrite Broadford Bike Bonanza. Despite this meeting having been on my “to do” list for many years, events have again conspired against me and the Easter Weekend has passed by. This year the event was dedicated to remembering the Castrol Six Hour Production Race, held for 16 years at Sydney’s Amaroo Park and Oran Park circuits.

For me this is more than just a little annoying being as I am an acknowledged Castrol Six Hour tragic. I attended the race religiously in the mid-70’s, photographed it and even served as part of the on-course commentary team one year. I used more film at Bathurst and the Six Hour than I did at all the other meetings I attended put together.

For younger readers of this column, a little background information. The Willoughby District Motorcycle Club, one of the most active and influential clubs in NSW in the early 1970’s came up with an idea for a race for production-only motorcycles around their home track of Amaroo Park, in the Hills district, north of Sydney, in the late 1960’s. It was to be very much a “club” event with the entry being open to all who wanted to ride and the entry list allowing bikes from 250cc up to unlimited capacity. The one stipulation that made the race unique, right from the outset, was that the bikes had to be absolutely stock standard with no modifications from standard of any kind being allowed. It was tantamount to going to your local dealer today, buying a bike, taking off the lights and the indicators and going racing.

And the club set out to ensure compliance with this requirement by employing a team of scrutineers who would rigorously check every bike entered to ensure that nothing on the bike deviated in any way from standard specifications.

The first few races were very laid-back compared to what we are used to today, but the big name riders were there from the outset and motorcycle dealers realised almost immediately the advertising value that could be gained from having their brand of bike win the Six Hour. Thus the grids quickly began to fill with the latest and greatest of the manufacturers’ inventory as the event became a showcase for what could be achieved with a modern motorcycle.

Sadly, the inception of the race coincided almost exactly with the release of Honda’s 750/4, for most commentators, the bike that sealed the fate of the British motorcycle industry. Despite many entrants entering British bike in the Six Hour well into the 70’s, the race was only ever won once by a Pommy bike, the inaugural race, a Triumph being ridden by Len Atlee and Bryan Hindle.

Andy Warhol is said to have coined the phrase “fifteen minutes of fame” but for the riders in the Six Hour, it was more like six hours of fame. The Six Hour, as it soon became known, became a compulsory event on the yearly racing calendar. Indeed, it was said that, while most people have two main events on their yearly calendar, Christmas and Easter, for road racers (and a fair proportion of dirt-track racers, too) their calendars revolved around Bathurst and the Six Hour. In fact, like the Easter races at Bathurst, which became the only event in the year that some riders rode, the Six Hour became the home of the “Six Hour specialist” also.

The race was huge, with the various (Japanese) motorcycle manufacturers, realising its advertising potential, heavily supporting the event through their local dealer networks. Accessory and tyre manufacturers got into the game almost from the outset as well and the rivalry between them became as fierce (and sometimes fiercer) than that which was happening between the bike manufacturers.

Hiring a media consultant, the WDMCC ramped up the advertising and soon the Six Hour was on everybody’s lips. The ABC came on board, doing a live telecast of the event each year, including the qualifying sessions on the Saturday afternoon at the height of their involvement. With the arrival of TV coverage, everyone lifted their game and team colours, matching leathers, stickers, give-aways and other novelties, all promoted by the teams, arrived.

But it was the action on the track that ultimately mattered. Almost immediately it became a required item on every rider’s CV to have competed in the Six Hour and winning the race was a passport to fame (if not fortune)

The race was first run at Amaroo Park, as previously stated. A tight little track with a lap measuring just 1.9kms, it was demanding, dangerous and technical. When told about the race, some years later, touring car legend Dick Johnson is said to have remarked that riding a racing bike around Amaroo Park for six hours would be somewhat like running a marathon around your clothes line. He wasn’t far wrong.

Throw in the fact that, for the first few years, the unlimited bikes were sharing the track with 250’s and 500’s, the idea of “speed differential” takes on a whole new meaning. Despite this, however, the accident rate remained relatively low given that the early fields consisted of 40+ bikes.

Since the bikes were assiduously checked so that no modifications of any kind could be made, it says wonders for those bikes which we today look back on as being very agricultural and crude, that the reliability was surprisingly high. This was probably the enduring legacy of the Six Hour that it showcased how astonishingly good modern motorcycles had become with the arrival of the Japanese manufacturers.

In 1984, amid growing safety concerns about the speed of the modern bikes and the ability of Amaroo Park to cope with it, the race was shifted south, to Oran Park, where it ran until the last race was run there in 1986. The purists (I count myself as one) will tell you that something was lost with the change. While the last three Six Hours were great events, something about the change of venue reflected a wider change that had been happening for a while and which the change really only brought to a head. From 1970, when bikes could still break down and have to be fixed by the side of the road, to 1986 when any decent bike would last for 160000kms before any major work was required, the manufacturers found that the advertising “clout” that a Six Hour win brought them was diminishing. The race had long ago ceased to be about who made the best, the fastest, bike; fact was, everybody did. “Win on Sunday – Sell on Monday” had been the catchcry but, with straitened economic times and increasing parity between the major manufacturer’s top-line offerings, the race wasn’t proving what it was originally proving when it first kicked off.

And so, 1986 saw the last Six Hour. Several attempts have been made to revive the endurance racing ethos of the race in the intervening years but all have foundered on the rocks of increasing expense, lack of interest from the mainstream media and the altered priorities of the manufacturer/distributor sector. The parity of the top sports bikes that bedevilled the last few events is still there.

Time and space do not permit a retelling of the multitude of stories that came out of this race (libel and defamation laws also preclude full disclosure!) Wheezes and tricks to try and sneak things by Chris Peckham (chief scrutineer) and his team would fill a book, too!

By the early 80’s Japanese manufacturers regarded the Six Hour as so important in their global marketing strategy that they started producing bikes especially for the race. “Production” became a very “loose” term. The Honda CB1100R was a “Six Hour Special” as was the wire wheel version of Suzuki’s GSX1100. And it wasn’t just the bike manufacturers who got into the game. With Amaroo Park being notably hard on tyres it was only natural that the tyre companies started to look for what publicity could be gained from producing tyres that could stand the rigours of six hours going around and around and around. Rumours and allegations about “Six Hour Specials” from the tyre distributors also abounded.

And the preoccupation with the equipment rather than the riders using it was a very palpable thing. Fans flocked to the circuit in their tens of thousands to see “their” bike do battle and bragging rights if “your” bike beat your mate’s bike were intrinsically part of the event.

To the purists, however, it wasn’t so much about the bike as it was about the riders. It took a special kind of skill and concentration to ride an early 70’s superbike around Amaroo. And, of all the riders who rode the Six Hour, one rider stands supreme, the diminutive Kenny Blake. Consider these statistics if you will.

He entered every race from 1970 to 1980. His record is as follows.

1970. 3rd in the 500cc Class on a Kawasaki H1 riding with Kel Carrick

1971. 6th in the 500cc Class on a Kawasaki S2/350 riding with Rob Hinton

1972. 3rd with Jeff Curley. Ducati GT750

1973. 1st riding solo. Kawasaki 900

1974. 1st with Len Atlee. Kawasaki 900

1975. 2nd riding solo. BMW R90S

1976. 2nd with Tony Hatton. BMW R90S

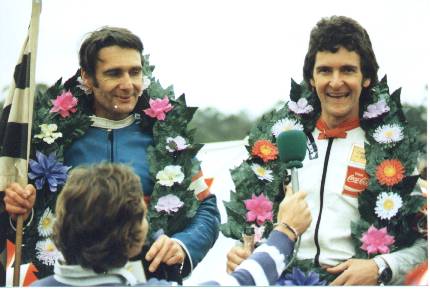

1977. 1st with Joe Eastmure. BMW R100S

1978. 4th with Dave Burgess. BMWR100S

1979. 8th with John Warrian. Honda CB900

1980. 23rd with Ron Haslam. Honda CB1100R (Haslam crashed the bike in practice and bent the frame.)

He raced 11 races consecutively, 9 times in the Unlimited Class. Of the 9 races in the Unlimited Class, he only once finished out of the top 10 (1980) and only once out of the top 5 (1979).

He scored 3 wins (1973, 74, 77), 2 2nds (1975, 76), 1 3rd (1972) and 1 4th (1978)

In addition he was the only man to win the race riding the whole six hours solo (1973) and the only man to finish 2nd riding solo (1975)

Kenny died at the Isle of Man, June 9th, 1981.

The only other rider who can hold a candle to Kenny was West Australia’s Michael Dowson. Dowson equals Kenny’s total of three wins but not his longevity in the race or his placings record in races which he didn’t win. It is very unfortunate that Dowson’s involvement in the race was at the very end of the race’s history for he surely could have won more often if the planets had but aligned correctly.

Nevertheless, the Castrol Six Hour has long ago assumed the position of a legendary series. Jim Scaysbrook’s brilliant book is a “must read” for any student of the race; web sites devoted to the race are still well-supported and the social media continues to be fascinated by it. Does absence make the heart grow fonder? In the case of the Six Hour, the answer is most definitely, Yes.