Testing Yamaha’s rider aids

By Adam Child – Photography by Gary Bailey

Consider how a Nokia phone was cutting edge 15 years ago. Now consider how archaic it seems today compared to the latest iPhone. Like phones, rider aids such as traction control and ABS have also developed at a rapid rate. The advancements in MotoGP and WSBK have filtered down to the end-user, me and you. What was high-tech on a MotoGP machine a decade or more ago is now similar to what you’ll find on a road bike.

Take Yamaha’s 2020 YZF-R1 for example, equipped with remarkably similar technology to that used by Yamaha in MotoGP in 2012. The list of rider aids has expanded from simple traction control and ABS to engine braking assistance, slide control, power modes, and cornering ABS to name but a few. And there is even more on the horizon.

Sophisticated rider aids no longer hinder your fun on the track, instead they boost your enjoyment while also making the experience safer. Rider aids are there to help you and can be easily customised to the way you ride, the conditions, and the bike. They are a tool to be used to get the most out of your bike and track day.

The idea is to show you how rider aids work, and what that feels like on track. I’ll test the R1’s rider aids fully activated, set low or switched off and then somewhere in-between to suit my style of riding and all on standard road rubber. We’re not going balls-out for lap times – this isn’t racing – instead, we’re getting the most enjoyment out of our track day, safely, while riding to the riders’ limitations. That is the idea of a track day…

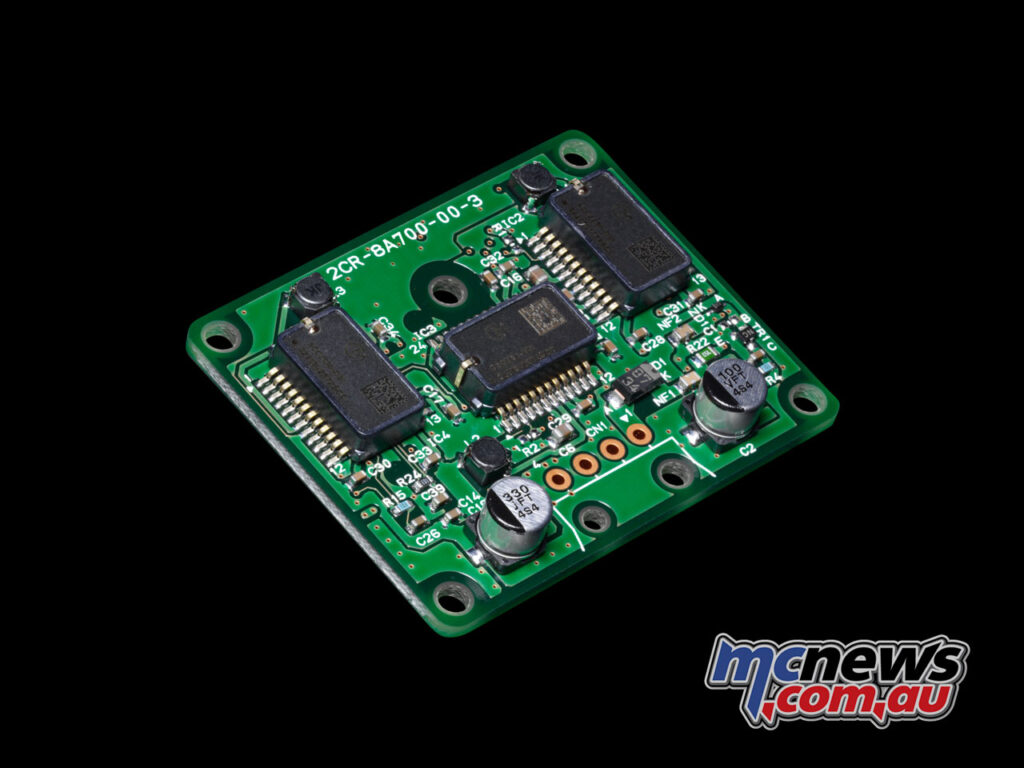

Most manufacturers use a comparable Bosch or Continental system, which is an ‘off the shelf’ item. The Bosch system is the brains, and each manufacturer tailors that system to work on their bike, to their parameters/algorithm. It’s a difficult procedure, but the base is already set by Bosch. The Yamaha system, however, is vastly different. Everything is done in-house and produced by Yamaha using the technologies learnt in racing.

Each manufacturer’s system is different as they use different tech and parameters. For example, manufacturer A might allow two per cent of wheel slip before any traction control intervention, and manufacturer B may allow five per cent of wheel slip, it all depends on the manufacturer.

Secondly, the level of tech may be different, some using the very latest generation, while others are using two or three-year-old tech. And finally, the power and the way a bike makes power, generates grip, brakes, etc, will differ too. It’s an incredibly time consuming, complex and expensive task to set up each bike, taking into account all the possible different scenarios.

A large percentage is done via clever mathematics, algorithms, and simulations, but there is still the need for endless laps and rider feedback in all conditions. Remember the rider aids must work for different riders, on changeable surfaces, and changeable tyres.

To highlight the complexity let’s take one example, traction control. The ‘system’ must detect wheel spin. Wheel sensors show the rear wheel is spinning faster than the front, then sends a message to the brain. The brain also gets a message from the throttle – ‘we are at 90 per cent open’, ‘the gearbox is in first gear’, ‘the crank speed shows rpm have risen dramatically’, faster than possible without rear-wheel slip.

It assesses all these messages and reacts accordingly, reducing the power so both wheels are once again rotating at the same speed. How fast this happens, how quickly these messages are sent, and how quickly it re-introduces the power depends on the bike and technology.

This is all done almost instantaneously, in the blink of an eye – actually less than that. It’s constantly monitoring as you ride, and will react dependant on the mode you’ve selected. Again for example, if you’re in Rain mode, the rider aids will be more intrusive, and act faster – hopefully.

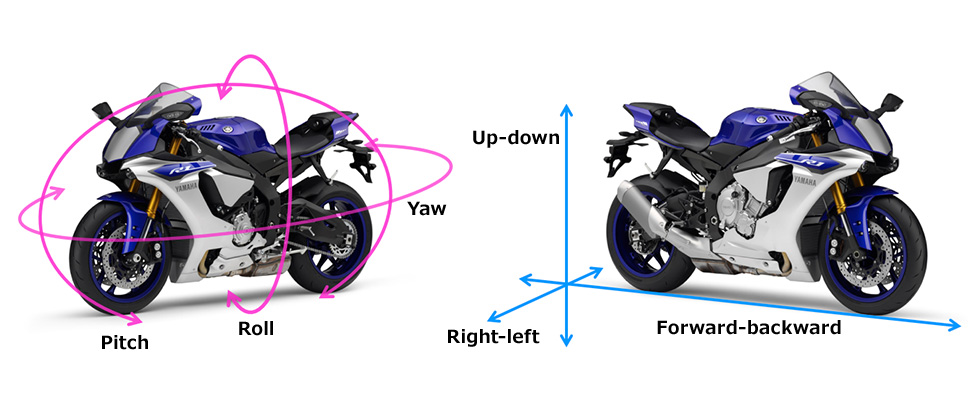

This is an extremely basic example as we haven’t spoken about the lean angle and G-force factors a modern IMU make possible, which the Yamaha R1 also takes into account. This is like describing brain surgery as opening someone’s head with a spoon – very simple.

Now time to test it

The plan is simple. After a few laps to get used to the track, Yamaha’s 2020 R1 and its standard Bridgestone tyres, we will try a full 20-minute session with the rider aids set to their highest level. Then we’ll have another session with the rider aids reduced as much as safely possible. Finally, we will take full advantage of the Yamaha’s electronic system and tailor the rider aids to match the conditions and the way I ride.

We’re not pushing for lap times or racing, we’re simply enjoying the bike and Silverstone safely, using the rider aids as a safety net. This is an experiment I’ve wanted to do for some time. All testing was done with suspension stock, tyres the stock Bridgestone S22s and with track pressures. Let’s go.

Session 1 – Rider aids set to maximum – Power 3, TCS 9, SCS 3, EBM 3

We’ve chose not to opt for Power-4, which reduces power to 70%. We performed the test at Silverstone, on the GP layout, the extremely fast F1 track. I didn’t fancy riding in fast track day traffic with just 70%, therefore, we opted for the softest full-power mode.

I was unsure what to expect. Years ago, early traction control set to maximum would transform a beautifully fuelled bike into a miss-firing bronco, but not anymore. In fact, as I leave pit lane with a huge handful of throttle the power takes me by surprise. Power mode 3 still gives a full peak output of 197 bhp just with less mid-range and a softer throttle, it’s quick.

First time down the Hangar Straight I’m overtaking slower bikes, despite being in the ‘soft’ mode. Don’t be deceived, the R1 is still a swift bike, but simply tamed in the low-mid-range. It’s far less physical to ride. It’s also much calmer out of the slower corners as I’m driving smoothly, not drifting wide on the exit.

The soft power makes the angry, snarling R1 as intimidating at a kitten. A new or relatively inexperienced rider would love this mode, which is fast enough to take your breath away and to overtake, but smooth lower down and forgiving too.

Don’t be deceived; you can still crash (especially on cold tyres), this is not a fool-proof motorcycle, but it’s almost comical how early you can accelerate while still leaning over. The soft power, combined with maximum rider aids, are the perfect recipe for boosting confidence, especially when the tyres are still coming up to temp.

Again, unlike the electronic systems of a decade or more ago, there is no misfire and no splutter, just controlled power. You might want 197 bhp on a cold tyre with 45-degree of lean but the bike knows best.

Braking is interesting, as there is less engine braking with EBM-3. This means the engine behaves more like a two-stroke as there is less mechanical braking, while the rear doesn’t lock up when braking heavily. You can’t feel the revs increase on the brakes, but the bike flows beautifully into the corners, especially into Stowe and Brooklands where you carry corner speed into the apex.

Session 2 – Rider aids set to minimum – Power 1, TCS 1, SCS 0, EBM 1

Like many of us, when I ride a bike with the rider aids turned off, I instantly feel nervous, despite growing up in an age of no rider aids. Out the pits and everyone else is on slicks with warmers and for the first lap everyone is overtaking me – in fact, I was quicker on lap one in session one.

But as the heat develops so does my trust. The standard R1’s feedback is excellent, you can feel the grip, but it takes more attention than before, and once we’re up to speed and temperature, I can push on for a quick lap. The throttle is more responsive, there’s more power on tap, the connection feels sharper.

When loading the rear tyre on the initial turn of the throttle, you can feel the standard Bridgestone move a fraction, then it grips and digs in as you dial in the power from the cross-plane engine. I’m going faster than in session one, accelerating harder out of turns, but probably accelerating later, waiting a fraction longer, getting the bike upright.

Without the engine brake assist, the now strong engine braking causes the rear to slide when you load the front tyre and the rear goes light. This was fine, not too worrying, but not ideal for a fast lap time and enough to worry someone without track experience. The longer the session goes on the more the rear standard Bridgestone starts to move around. Keeping in mind setting 1 (out of 9) on traction control is for slicks, with warmers, not road rubber, which is designed to work in all conditions, including the wet and cold.

Session 3 – Rider aids set to ‘in between’ – Power 2, TCS 2, SCS 1, EBM 2

Power mode 1 was a little too aggressive, too sharp, so I’ve opted for 2. I’ve turned back on the slide control and left traction control on 1. Engine braking is in the middle at 2 because I still want some engine braking but not enough to slide the rear.

Now I’m happy, it feels like I’m riding my bike, which matches my riding and the rubber on test. We’re not on elbow-dragging slicks, which is why I’ve added a little bit of slide control and traction, just to give me a safety net. I can get on the power early with confidence, knowing I have some rider aids to help. The power is strong, but the instant turn of the throttle is a little easier. I’m not pushing for lap times but want that extra drive in the mid-range to overtake safely.

The engine braking is precisely where I want it; the rear no longer skids and slithers into corners, instead it’s nice and balanced with just enough engine braking. For a 20-minute track session, I’m lapping reasonably quickly, safely, hitting my markers without too much determination, and I’m not out of breath on the last few laps. We could have opted for something more aggressive, but it’s a track day, not a race.

Final session – Power 3, TCS 3, SCS 3, EBM 2

How many times do you see track day riders packing away before the last session because they are tired? How many times have you heard, “I don’t want to push it in the last session?” Yes, that is a wise decision, and I was tired after a full day on track, which is why, rather than head for the pub, I simply increase the rider aids for the last session.

Back to the softest power mode to make life simpler, I also increase the traction and slide control on the rear as the Bridgestone is now badly worn, and leave the engine braking alone. I’m riding a little slower, but still having fun. Even in power mode 3, the R1 is still rapid, and I’m still tucked in on the 160 mph-plus straights, but the acceleration is tamer. More rider aids are controlling the grip, which gives me more time to choose the correct line, and essentially be a little lazier. While some are packing away, I’m still smiling and having fun, all in relative safety thanks to the rider aids.

Verdict

Rider aids are so good, it almost feels strange and intimidating to ride without them. Yamaha’s R1 is a proven example, you don’t really ‘feel’ the rider aids working and there aren’t any misfires or alarming spluttering, instead they are an arm on your shoulder holding you back from doing something untoward, like an older brother stopping you from doing something stupid.

Additionally, they are simple and easy to trim, depending on your abilities and where and how you ride. In perfect conditions on slicks, yes, I might choose to remove the rider aids, but back in the real world, I’ll take modern rider aids every time.