Yamaha YZF-R1 History

Rennie Scaysbrook

The year is 1998. Yamaha launches the first edition of the YZF-R1. The world’s press publications are gob smacked, and the company can’t keep up with demand. Waiting lists blow out for salivating customers, and Yamaha’s rivals have been caught with their pants down.

The 1998 Yamaha YZF-R1 is the granddaddy of the modern superbike. Until its release (and for some time after it), superbikes were classified as 750 cc four-cylinder machines and 1000 cc twins. World Superbike would keep these rules until the end of 2002, but in reality the world had moved on in 1998.

The R1 saw to that. The R1 also saw the death of the ’90s litre-class hyperbike (an over-exaggerated term common at the time for any sportbike bigger than a superbike), which arguably began when Tadao Baba released the mighty 1992 Honda Fireblade – a 900 cc inline four-cylinder – that made fellow four-cylinder combatants like the Kawasaki ZZR1100 and Suzuki GSX-R1100 look like also-rans.

Sportsbikes at the time were primarily designed as roadbikes, not racers with lights. The R1 was the first to take this way of thinking and junk it. Comfort was reduced to the bare minimum in the name of pure speed.

Even things like a handy boot under the seat – like the Fireblade had – were regarded as unnecessary. Anything that didn’t need to be there was scrapped. The 998 cc R1 was designed to be the lightest, shortest and most powerful machine ever created in the 1000 cc class.

It was designed to handle with the agility of the company’s YZF600 ThunderCat (then its leading Supersport 600 machine), but have power levels normally reserved for factory WSBK riders Scott Russell and Noriyuki Haga. A sports-tourer the R1 was not.

A clean sheet of paper

The mid-’90s was a bleak period for superbike sales, and Yamaha realised that although the long-standing YZF750 was a good performer on track, the sales success didn’t reflect it.

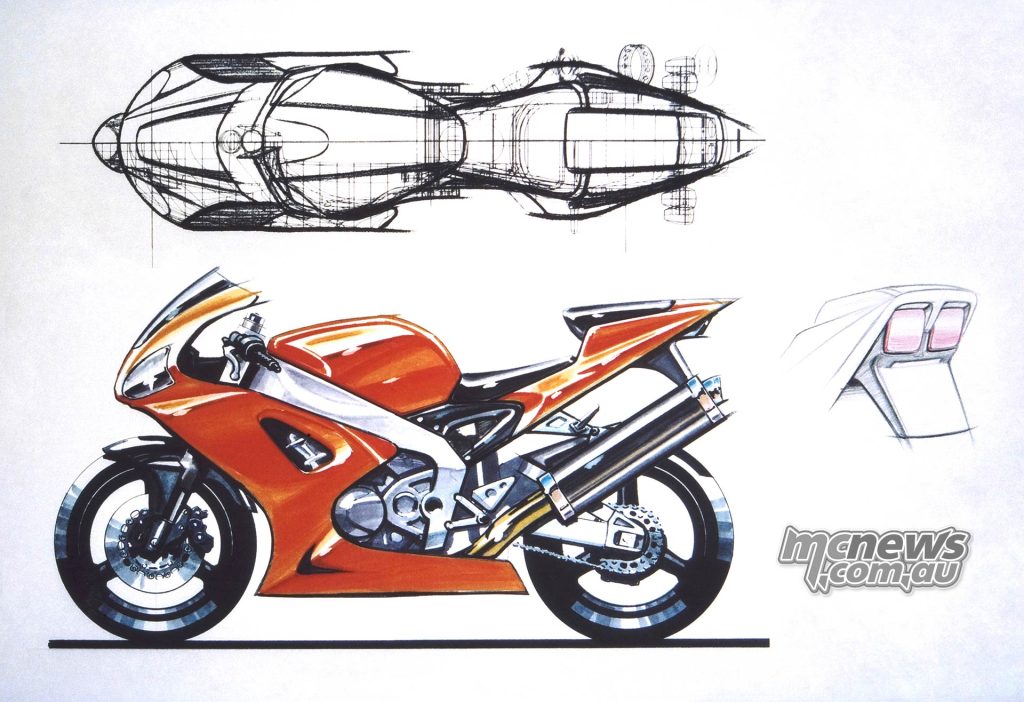

As such, designer Kunihiko Miwa was given a clean sheet of paper to build a new supersports machine, right around the time the Yamaha YZF1000 ThunderAce was given a freshen-up in 1997.

The ThunderAce had always been a reliable performer for the Tuning Fork brand, and the 1997 version was indeed a fine machine.

It had plenty of power from the five-valve, inline four-cylinder engine that could trace its heritage to the FZR1000 of 1989, with a well-balanced chassis and good ergonomics, but it still belonged in the Suzuki GSX-R1100 weight class and would hardly do as a racer with lights.

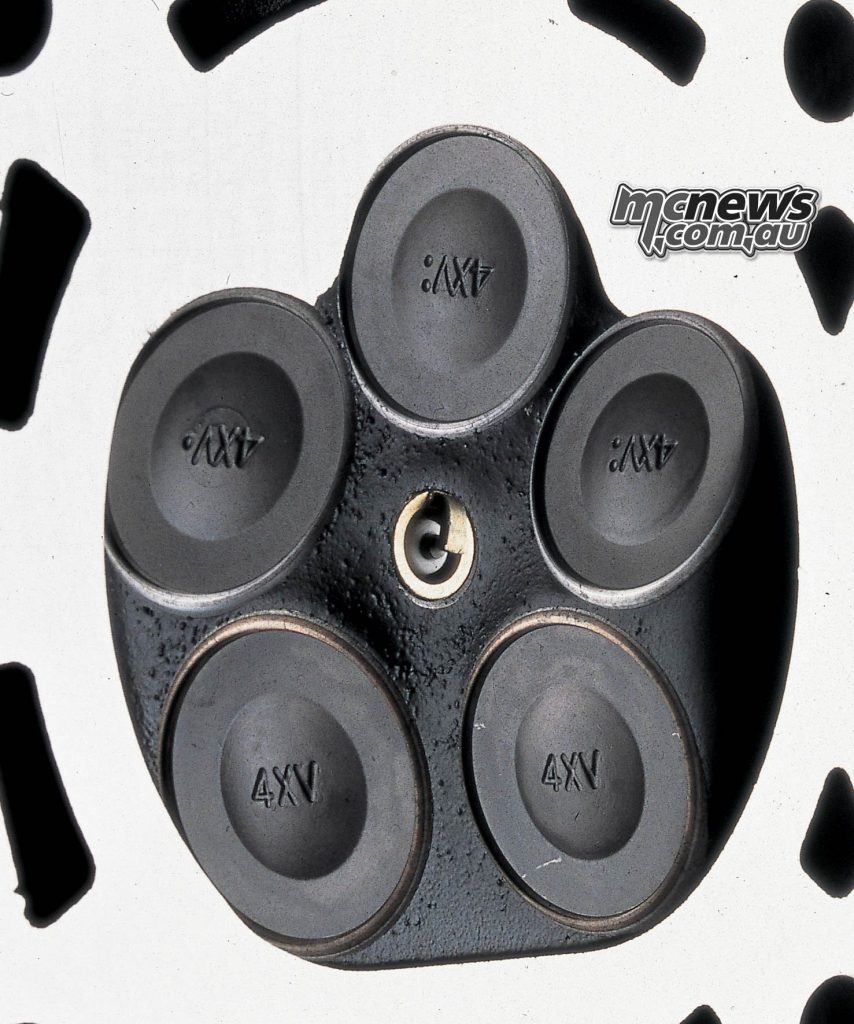

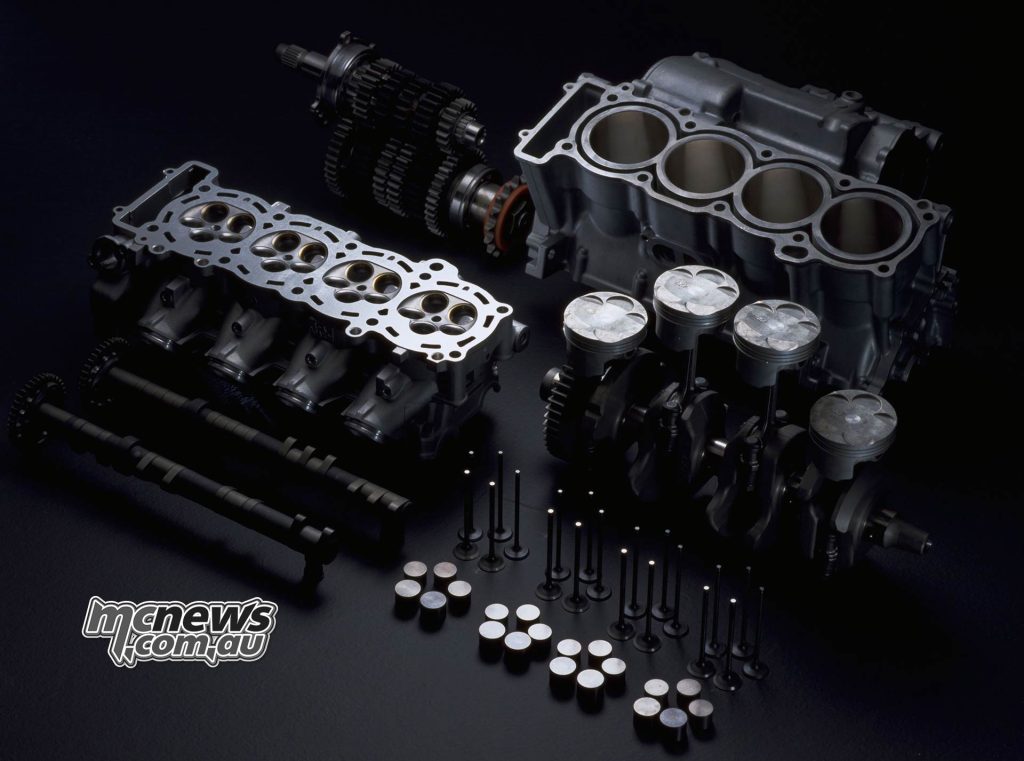

That being the case, Miwa-san took the basic YZF1000 engine and pulled it to pieces. The R1’s engine was still to retain the company’s sacred five-valve cylinder-head, but that’s about where the similarities between it and the ThunderAce ended.

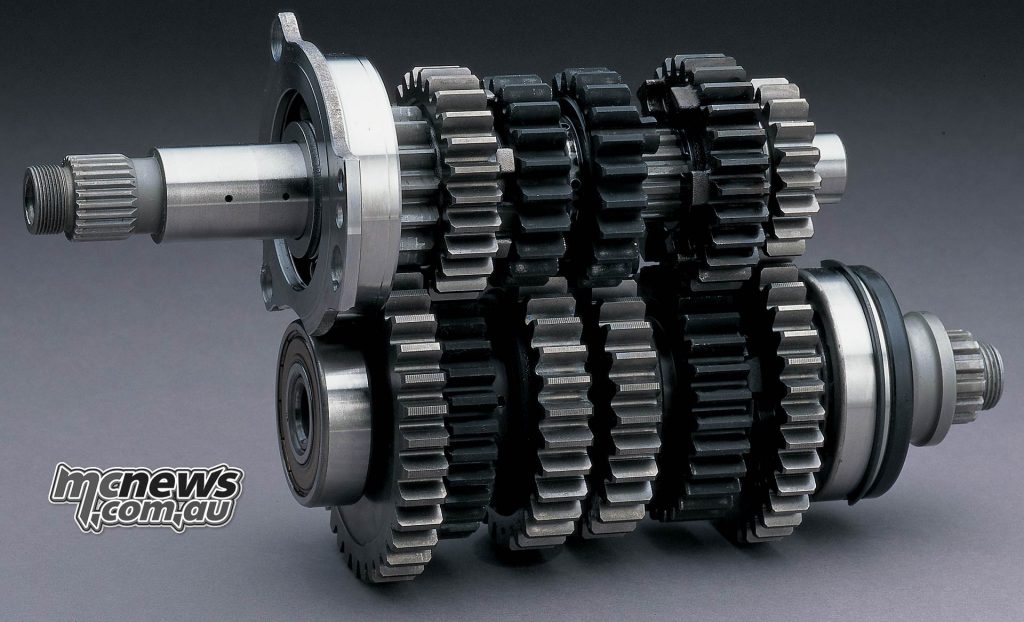

Miwa-san came to the conclusion that the traditional engine layout where the crankshaft, drive shaft (countershaft sprocket) and main shaft were all in a line represented a drastic waste of space, so he came up with the ‘three-axis’ design, where the main shaft was offset and positioned above the crank and countershaft sprocket, closer to the crank.

This was soon adopted by the industry, and is now the only way to go if you want to build a serious in-line four-cylinder superbike.

The new design also meant the clutch could now be mounted higher, with the cylinders and crankcase cast as a complete unit.

This also allowed Miwa-san to turf the traditional cast iron cylinder liners, the bores now treated to the Yamaha-patented electro-deposited low-friction ceramic coating.

Even the layout for the oil filter and cooler was redesigned, sitting side-by-side at the front of the block rather than being stacked, as per conventional thinking.

This gave Miwa-san the ability to mount the headers of the four-into-one exhaust system – featuring a revised version of the EXUP (Exhaust Ultimate Powervalve) system – closer to the engine, giving him more clearance for the front wheel and thus making the front even more compact.

The difference between the R1 powerplant and that of the ThunderAce was not just external size. Internally they may have shared the five-valve head, but the R1’s inlet ports were smaller and inside the head sat smaller valves at a steeper angle.

The blocks were different too, with the R1’s bore and stroke measuring 74 x 58 mm compared to the shorter stroke figures of 75.5 x 56 mm for the ThunderAce.

Below deck the crankshaft came in for the Jenny Craig treatment. Yamaha engineers managed to shave an impressive 22 per cent off the reciprocating mass of the crank, which was a major factor in the R1’s impressive throttle pick-up. Swinging off the crank were new con-rods with lightweight forged aluminium pistons.

Even though the two engines shared a claimed torque figure of 107 Nm, the R1 – which carried an 11.8:1 compression ratio to the ThunderAce’s 12.0:1 – made that figure 1500 rpm lower at 8500 rpm. It also had an extra 5 hp, with a claimed 148 hp at 10,000 rpm.

Those were serious figures for 1998. The Honda Fireblade, which for 1998 had grown to a 919 cc engine, claimed power and torque figures of 130 hp at 10,500 rpm/92 Nm at 8500 rpm.

Kawasaki’s ZX-9R, which was also revised for the 1998 model year, produced 143 hp at 11,000 rpm and 101 Nm at 9000 rpm.

These were still the days before fuel injection became commonplace in production sportsbikes, and rather than get a jump on the pack by fitting EFI, Yamaha instead chose to furnish its new weapon with 40mm BDSR Mikuni carbs, which were 30 mm narrower than the ThuderAce’s 38 mm units.

The R1 ran a throttle position sensor, which was also linked to the CDI unit, gear position indicator and the EXUP valve, and programmed to increase the available torque from 4000-8000 rpm.

Getting all that grunt to the tyre was a new six-speed gearbox, replacing the five-speeder in the ThunderAce.

This new gearbox became one of the few weak points in the 1998 R1’s armour, but thankfully Yamaha engineers were wise to this by 1999. Even though the model was only slated to have a paint scheme update – they fitted a redesigned gear change linkage and increased gear change shaft length to stop it popping out of gear, particularly second gear.

The 1998 R1 was also the subject of a worldwide recall, with several cases of the clutch-driven gear drive plates breaking, causing the engine to lock up.

But regardless of the faults, whatever angle you looked at the new engine, it was a class ahead of everything in 1998. The design brief of smaller, lighter, faster was certainly met.

The new engine was 81 mm shorter front-to-back than the ThunderAce, and 20.9 mm shorter top-to-bottom. However, unlike the engine, the chassis had no platform for modification.

It was to be all-new – shorter and lighter, with racier geometry than anything with a headlight gone before it. Yamaha claimed the new bike weighed 177 kg dry, which when you add a tank of fuel, would put it close to the 200kg mark.

With the engine being so small, Miwa-san could focus more on mass centralisation than ever before. The engine was a fully-stressed member of the chassis, which helped add to the rigidity of the package…

Use the navigation below to continue to the next page