Snapped – Motorcycle road racing photography – A column by Phil Hall

Indulge me for just a little if you will while I discuss the subject of motorcycle road racing photography.

I started taking photographs when a relative gave my brother and I a little camera each in about 1962. I can’t remember much about it, but it opened the door to a fascinating world. Then, for Christmas in 1964, a friend of the family gave us both an Instamatic 100 camera. Drop-in film cartridge, no hassles with bits of film flying around everywhere, it was the original PHD (Push Here, Dummy) camera.

Later on I graduated to a 35mm rangefinder camera (Yashica Minister III) and then, in January 1976 I lashed out and bought an SLR, A Practika LTL. Made in what was then East Germany, it had a built-in light meter and interchangeable lenses, wow. It was also heavy as a brick being made (so they say) of recycled metal from WWII tanks and it opened up the world of more advanced (relatively) photography.

With it I started taking road racing photographs, the camera’s arrival coinciding nicely with my first race meeting, at Laverton in February of that year. Photographing from the spectator stands was a challenge that was made a little easier due to the purchase of a 300mm telephoto lens (fixed focus) and a 2x Teleconverter. I did the next couple of meetings back home with that setup but quickly realised that, if I wanted to take GOOD photos then I had to get INSIDE the fence.

Things were a little more relaxed back then and it didn’t take too long before I found myself being given a photographer’s pass at every meeting which allowed me free access to the areas that were verboten to the spectators. Here I started rubbing shoulders with some of the greats of the game in the day and also learning the craft of racing photography. There was no internet so library books were the means whereby valuable information was stored and disseminated and I read voraciously, fretting till the next meeting arrived so that I could try out the new techniques.

I also found that, in talking to the riders, hardly any of them had any pictures of themselves. The “Pro” photographers with whom I had nodding acquaintances were nearly all taking photos exclusively for magazines and periodicals and the best the riders could hope for was photos taken through the fences by friends and colleagues.

Thus my brother and I started cultivating a little niche in the market. We would cruise around the pits before the racing started and ask if riders wished to have photos of themselves taken on the weekend. Usually, the answer was yes and so, along with taking photos for ourselves as something that was fun to do and something that would be a record of the meeting for us, we started taking photos “to order.”

Once the meeting was over, we would get our films processed, printed and then, at the next meeting, we would show the proofs (direct contact prints from the film, 35mm x 24mm) and take orders. We would then put the appropriate negatives in to be printed and deliver them to the appropriate people at the NEXT meeting and receive payment (usually).

We pretty rapidly parlayed our little hobby into a business that didn’t break any records but usually covered our processing costs with a bit over the top.

In 1977 I upgraded to a Pentax SP1000 and lashed out for an 80-200mm zoom lens that gave me vastly better results as well as versatility. It was this combo that saw me through the next four years of taking photos around the tracks. We travelled as much as the budget allowed; living in Canberra meant that all venues required long drives but we became regulars at Amaroo Park, Oran Park, Bathurst and Hume Weir. A yearly pilgrimage to Sandown Park in Melbourne for the Swann Series round there was also a “given.” Sadly, costs militated against travelling any further than that so I never made it to PI in the day, nor Lakeside while it was still running.

Once I started into race commentary (another story for another day) my photography took a back seat so, while I worked intensively in the game, it was only for a relatively short period of time.

Fast forward to 2011. While recuperating from my big “off” I relieved the boredom by scanning in all of my negatives (B&W and colour) and slides and storing them on my computer. The end result was about 3000 images, a piddling amount by today’s standards but a fair body of work when one considers that the number represents hundreds of films. As I started cataloguing them and publishing them in albums on the Internet, it amazed me that I remembered most of the bikes and riders, race meetings and details, despite the last photos having been taken 30 years previously. I have been told that this is an example of “selective memory” the capacity of the human brain to remember the things that are important and to filter out the things that aren’t!

When I started attending road race meetings again post-accident, I was also working for a media company that had me recording voice interviews with riders and officials for publication on a podcast. Because of this I had access as a member of the working media as well as access to press room facilities at the big meetings. Obviously, even though my priority was voice recordings, I was free to photograph and so I did. I had been given a new digital SLR for Christmas so what better opportunity to give it a hiding than by taking hundreds of photos in the pits?

Though my media credentials allowed me to go out on the circuit and photograph, I have not really taken advantage of that, even though I am sure that the skills would come back. But my injured leg objects strongly to walking long distances, climbing fences and clambering in and out an up and down to get the best vantage points. As well as this, I have lost the speed of movement that I once had and I am pretty sure that, if I had to get out of the way in an emergency, I would be unable to do so. So, while I’d like to get out there in the thick of it, I have chosen not to do so except for a couple of brief forays.

So I guess that I am pretty well-placed to comment about motorcycle road racing photography and, what I am going to say may not be popular with some who are presently plying the trade. Let me explain.

The Media Centre at Phillip Island is a large room above the pits. It’s probably 40 metres from one end to the other and it’s as wide as the pit garages underneath it. It is staffed by the most wonderful, hard-working and obliging bunch of people you could ever hope to meet and it is always a pleasure to work there. Nothing is too much trouble and the staff go out of their way to make sure that the working press get to do their job as efficiently as possible.

But the first time I went there I noticed something very disturbing. The room consists of rows and rows of tables spread across the room, serviced by an aisle down the middle of the room and aisles on each side. At any race meeting where it is in use, you will see rows upon rows of journalists and photographers from all around the world, poring over their laptops and working hard to produce the product that their editors expect. And it was their laptops, and what was on the screens of their laptops that disturbed me when I first saw it and continues to do so. For, if one were to stand at the back of the room and scan the computers, one would see that almost every screen is filled with pictures of racing bikes, but, almost without exception, the pictures are all the same! Yes, dozens of hard-working photographers are sweating it out in the sun, recording the meeting for journals and magazines and for posterity too, but they are all taking the same photographs!

I thought I’d do a little experiment so I walked (slowly) from the pits down to Turn 4 (hereinafter to be known as “Pedrosa’s Folly”) and what I had suspected was proven to be the case. As one of the races was about to start I saw about 10 photographers, all jockeying for position so that they could take the same photo of the bikes braking for the tight corner. Like little robots, they waited, snapped a hundred frames as the bikes appeared, then waited to repeat the process on the next lap. Lap after lap it was the same until the race was over. It didn’t appear that there was too much work involved, get a huge lens and point it at the corner. I am guessing that there is more to it than that, but, if there is, I am not sure what the justification is because, back in the media room, guess what? All the photos on their laptop screens looked the same!

Now this is not intended as a swipe at the working media, many of whom I know and greatly respect as people, but it IS a plea for some creativity, some photographic FLAIR when doing the job. Where is the ORIGINALITY? I am sure that these people are vastly more talented, experienced and dedicated than I am, but the end result seems to be much too formulaic, too sterile, for my liking. Yes, the photos are crystal clear, brilliantly so compared to the stuff that I produced back then. Yes, this may be what the editor wants, and, if that is so, then you give the editor what he wants even if it goes against the grain. And don’t get me started on “enhancing” of the photos with Photoshop and other digital editing tools.

There are many arts to photography and, no matter how good you are, or how experienced you are, there is always more to learn. But, let me ask you this. When is the last time you saw a “commercial” photo that was anything different from the standard 3 or 4 stock layouts favoured today? When is the last time you saw a good “panned” photo where the bike is in focus and the background is blurred and the bike is moving PAST the camera not towards it? I’m sure they are out there, but they sure don’t appear to be part and parcel of the modern photographer’s arsenal.

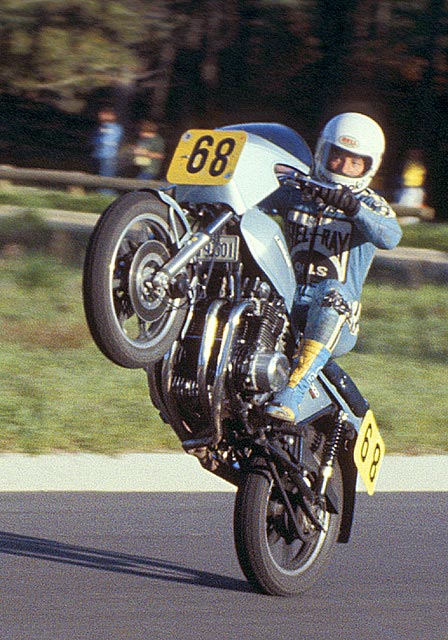

The greats of my era, people like Lou Martin, Robin Lewis, the artistic Greg McBean and the peerless John Small whose iconic picture of Crosby wheelstanding the Z1R at Macarthur Park has gone all around the world over and over again, worked with antiquated equipment by today’s standards. They had the constraint of often not even having a motor drive, winding on after each shot manually. They had smaller lenses and they had no means of previewing their photos immediately after taking them in case something wasn’t right and they could take another one next lap.

And yet, they produced quality photos that have stood the test of time and photos that had originality, creativity, flair and sense of “being there” that seems sadly absent in the offerings of today. Perhaps they didn’t have quite the pressure of demanding editors and sponsors like today’s photographers do but I like to think that, even if they had, they still would have delivered the goods.

I make no claim, nor have I ever made the claim, that I am a great photographer. But I do recognise what is flair and creativity and I am sad that it appears to be missing in much of what is published today.

I am now going to retreat to a safe distance and put on my suit of armour while the rocks and missiles start raining down.