Honda MVX250F with Phil Hall

Orphan is not a term that we hear very much these days. When I was growing up in the aftermath of WWII, it was in common usage as hundreds of thousands of children in the war-torn countries had lost one or both of their parents in the conflict. It is good to remember that, because, in light of our recent reflections on ANZAC Day, we tend to forget that, along with the shocking loss of life amongst the combatant troops, a multitude more deaths occurred amongst the civilian populations of the territories over which the war was waged than amongst the soldiers waging it.

But this article is not a reflection on war. Rather it is a reflection on some of the motorcycles that “slipped through the cracks”; that arrived and disappeared almost as quickly; that fall under the heading of “It seemed like a good idea at the time.” And I want to start with one from my favourite manufacturer, Honda.

It is 1982. Honda had finally abandoned the attempt to win the 500cc World Championship with its preferred weapon, the four-stroke NR500. A hideously complex machine that was a blatant attempt to circumvent the FIM ruling that 500’s were limited to four cylinders, it had an embarrassing debut at the British Grand Prix in 1978 where both bikes were too slow to actually qualify. To save face, they were allowed to race anyway but they probably shouldn’t have. One bike crashed on the first corner and burnt and the other didn’t make it to the finish line.

Riders, Mick Grant and Takazumi Katayama bore the chagrin with typical aplomb but the writing was plainly on the wall. If only Honda had taken the warning as an omen and quietly pushed the NR (wags at the time suggested that the initials stood for “Never Ready”) into a quiet corner of the factory and covered it with a tarp. But they didn’t as they were determined to prove that a big, heavy four stroke could defeat a light, powerful two stroke. Looking from the outside it is evident that it was only the Japanese fear of losing face that stopped them from calling it quits right then.

Honda continued to race the NR in its constantly evolving iterations until the early 80’s, never winning a Grand Prix and, when the plug was finally pulled on the project, the unfortunate bike had but one win to its credit despite the millions of dollars and man hours that had been ploughed into its development. That was in a domestic race in the USA and the rider was Freddie Spencer. Many have suggested that it was only the extraordinary talent of Spencer that got it the one win it got anyway.

But now Honda had bowed to the inevitable, introducing a two stroke grand prix bike, the NS500. But even here, they decided to plough their own furrow. All other 500cc manufacturers were using four cylinder engines but Honda decided on a THREE cylinder layout. Perhaps the experience of trying to make a big, fact bike go fast enough to win had something to do with it but they decided that they could beat the big (relatively) heavy four cylinder machines with a little and light three cylinder one.

Given that it was Honda’s first foray into the world of two stroke technology, it was a brave move indeed but it paid off. Through a wonderful confluence of circumstances, Honda had the right bike AND the right rider at the same time. Freddie Spencer, hand chosen by the Honda hierarchy as the one who would fly the flag, dutifully did what was expected of him and lifted the 500cc crown in 1983 after a titanic battle with fellow countryman and Yamaha rival, three times World Champion, “King” Kenny Roberts.

The lifespan of a grand prix bike can be painfully short, and it certainly was so in the case of the NS500. One and a half seasons and it was gone, consigned to the technological scrap heap with the arrival of the NSR500, a full four cylinder machine which was to dominate grand prix racing until nearly the end of the next decade.

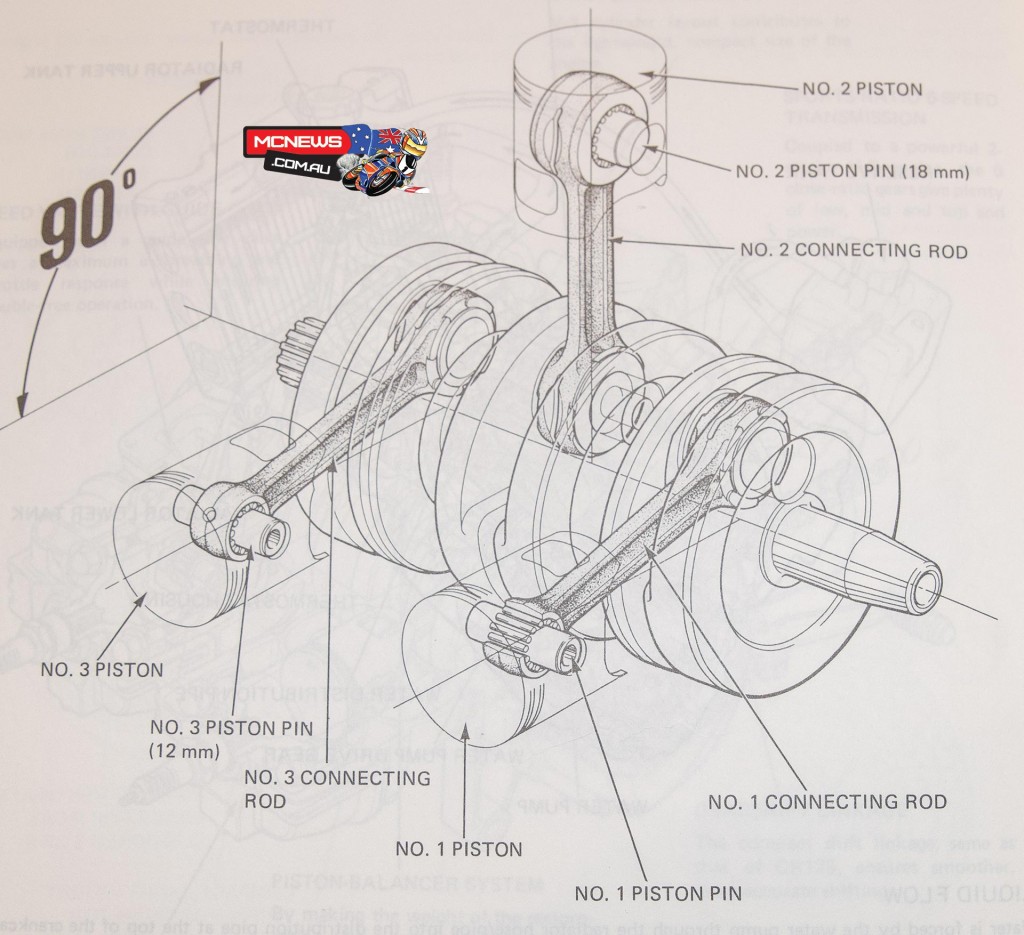

In design, the NS was radical and clever. Its engine is described as a V3, probably because that is the closest way of describing the interesting engine layout. In fact the engine was really an across-the-frame three cylinder and was as wide as one would have been if that layout was strictly applied. But the middle cylinder was splayed out from the other two and pointed forwards, the two outer cylinders laying back. So it was a sort-of V. No doubt with ideas of mass centralisiation, Honda kept the bulk of the engine near the centre of the bike. Also no doubt with a view to cooling, the middle cylinder kept the two outer ones apart and allowed for all three cylinders to be in an air stream even though the bike was, of course, water cooled.

This design also allowed for a much lower centre of gravity and helped contribute to the legendary “flickability” of the NS. Honda’s idea of sacrificing top speed in the interest of better cornering, braking and acceleration out of corners was a winner and, combined with Spencer’s “point and shoot” riding technique, it was easily the best bike of 1982-3.

Now, all of that is, as W S Gilbert said in “Trial by Jury”, “Merely corroborative detail intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative.” Where does it fit in with my examination of motorcycling orphans? Well, I probably should note that none of the bikes that I am going to look at are really orphans in the strict sense of the word. They all have parents and we know who their parents were. But they ARE orphans in the sense that nobody seems to want them, their parents included, and that fact that their parents abandoned them soon after their birth seems to indicate that the name is appropriate.

My first orphan is the Honda MVX250F. Produced for just one year, embracing parts of 1983 and 1984, the MVX is probably the bike whose mention in any bench racing session is most likely to draw blank looks from most people involved in the discussion. But it really shouldn’t because it was a most interesting and ground-breaking design. Firstly, and most importantly, it was Honda’s first two-stroke road bike. Given that Honda had been churning our road and racing bikes since 1949, it is a testament to their commitment to suck-squeeze-bang-blow that it wasn’t until 34 years later that they produced a two-stroke road bike.

And it was also typical of Honda’s corporate thinking at the time that it was produced at all. All Japanese manufacturers of the day were obsessed with producing a model to plug every single capacity class and motorcycle type in the market. The array was bewildering with a veritable alphabet soup of models, capacities and genre that the dealers and road testers struggled to grasp and that the normal punter in the street had virtually no chance of mastering.

And, of course, the MVX was a “celebration” model, rushed into production and onto dealership floors to cash in on Honda’s new wave of two stroke grand prix machines. Like the NS500 it had a V3 engine, but, unlike the grand prix machine, the cylinder arrangement was the opposite, with the two outer cylinders laying forward horizontally and the middle cylinder standing vertically. It was a “sports/commuter” model and proved very popular in the domestic market where small bikes were the norm. It was only ever exported to Australia and New Zealand (who knows why – perhaps the USA was a bridge too far with the looming EPA blitz on engine emissions, or perhaps Honda tacitly acknowledged that America was a “big bike” market).

It produced 40bhp in a bike that weighed just over 150kgs wet so it wasn’t a ball of fire, but it was certainly brisk enough for the day. Other technology that made it interesting was the use of Honda’s enclosed disk brakes where the disk was fixed on the outer periphery, the caliper gripped it from INSIDE and the whole arrangement was enclosed in a metal, ventilated casing. This arrangement certainly meant that the brakes worked in the wet, something most exposed and stainless steel disks on Japanese bikes did not, but the penalty was weight, and unsprung weight at that, the enemy of good handling. Having had many years of experience with the type on the various CBX550’s I owned, I can tell you that the trade-off is probably just fractionally to the negative.

The fatal flaw in the overall concept of the bike was vibration. The V3 layout as produced made for a very “shaky” motor, not an especially worrying thing in a race bike but to be avoided in a road bike. Now there is a school of thought that two strokes SHOULD vibrate; as someone who owned an RD250 and who got to rode an RD350LC I can tell you that they certainly did; it’s part of the charm, but the V3 apparently vibrated too much, so Honda’s “solution” was to make the connecting rod for the vertical cylinder thicker and heavier than those for the horizontal ones. The heavier conrod would become a balance shaft of sorts, helping to damp out some of the more violent vibrations, and it seems to have worked.

But it also became a weak point for the whole engine and real-time usage of the bike saw catastrophic failures of the conrod in the vertical cylinder. In a model that was going to last a long while in the market, a solution for this would, of course, have been found, but the MVX was slated for obsolescence almost from the moment it hit the showroom floors and, no sooner had it arrived than it was gone, the problem gloriously unresolved.

A Honda MVX250F was raced at Bathurst, locals finding that jetting the vertical cylinder richer than the other two cylinders helped prevent engine damage. We also believe the Honda MVX250F won a race at Bathurst but have been unable to dig out the official records to verify.

There was another reason for the comet-like life of the MVX. The main competition for the MVX came from Yamaha’s brilliant LC model, a bike with style, clout, a racing pedigree a mile long and a raft load of companies producing hot-up bits to make it go even faster than it already did. It really was no contest.

And so the brilliant little MVX, Honda’s first two stroke road bike, came and went and its passing went virtually unnoticed. Every now and then someone will mention it and someone will say, “Oh, yeah, I remember them.” but that’s about it. Occasionally one will turn up on ebay, usually in scruffy and unloved condition and it will, like as not, go again without attracting a bid, not unlike what it did when it was new, a sad parallel and a sad postscript for an orphan that never really found a home.