Around the world with The Bear – Part 11

The King of Every Kingdom

Around the world on a very small motorcycle

With J. Peter “The Bear” Thoeming

When we last left The Bear, he was exploring the wilds of Pakistan, and now he heads into Afghanistan with an eye on visiting Bamian, despite some visa limitations…

Afghanistan

There are only two categories of the compulsory Afghani vehicle insurance—vehicles with more than eight seats or fewer. This meant that we had to pay the same rate as a car. But we got our own back on the Customs bloke.

He only knew three words of English, ‘I must look…’, and he kept saying them as he stood in front of our carefully packed and locked machines. We said ‘OK, look,’ and ignored the fact that he wanted us to unlock everything. He was actually rather nice, and finally took readings from our odometers to cover his embarrassment and left, muttering ‘I must look…’ I presume he was headed for his English teacher.

If you don’t understand our glee at beating the Customs for once, you’ve never been through a bad border. Our joy didn’t last long, of course. Karma struck. Within a few minutes, still in the pass, I had a flat tyre, our first on the trip. There was a largish tack in the front tyre, which we fixed as quickly as possible, because it was hot again and there was no shade.

Kipling didn’t know the half of it. He’d never had a flat tyre, for example.

We were well and truly out of the monsoon now, and would see no more rain until the Black Sea in Turkey. Jalalabad, the first stop north of the Khyber, was a friendly if slightly rough town, and we stopped for one of the local hamburgers and 20 or so bottles of Coke. The old bloke deep-frying the meat asked us if we wanted salad. Is the Pope Catholic? Of course we wanted salad. He gave us each a great handful of roughly chopped onion.

Then on to the middle of town where there was an intersection featuring a lot of those fiddly little cement islands, meant to channel traffic in the right directions. We were still getting used to riding on the right—it changes at the Afghani/Pakistani border—and wove our way around in different but about equally wrong paths. The policeman on point duty watched, first with an open mouth and then with a huge grin.

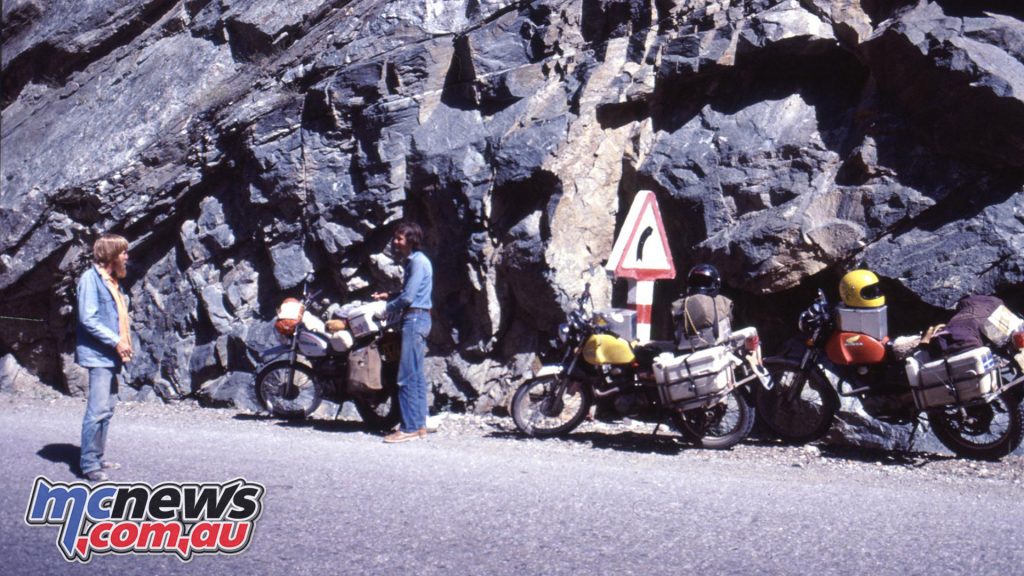

We swam in the icy Kabul River just below Kabul Gorge, one of the most spectacular bits of road building around. The road just climbs up a vertical rock wall, with switchbacks and tunnels every few yards. At the top of the gorge an XL250 went past us, going the other way. Huh? Paul, the rider, was on his way home to Australia from Britain. He had made the mistake of riding at night in Iran. A broken arm had taught him not to do it again.

At a roadblock near Kabul, the army checked our papers. The officer in charge looked at our passports and said, ‘Aha, Australia. So you do not speak English?’ We solemnly shook our heads and he waved us through.

Next came our introduction to the Great Game, of buying petrol that is. To understand how this works, you must know that the pumps only show quantity, not price. So you fill up and give the attendant some money. He stands there and smiles at you. You hold out your hand and demand change.

He gives a little start – oh, sorry! – and gives you a little money. Then he stands there and smiles at you again. You repeat your act, he repeats his. This goes on until you either have all your change or give up in disgust. It’s best to have the right money in the first place. You can actually work out the cost because petrol costs the same all over the country.

There was no trouble finding a hotel in Kabul; we ended up in what looked as if it might once have been a substantial bank. Then it was out for dinner on Chicken Street, a thoroughfare full of shops selling genuine antiques. Once again, not that kind of genuine – although I once bought a sword here which was genuine if dilapidated and which got me into no end of trouble in Singapore.

We ate delicious minced-goat kebabs and drank delicious tea in one of the many filthy, comfortable chai khanas or tea houses, and took stock. Our visas weren’t long enough for us to take a trip up to Bamian, but we both wanted to see it – in my case again. One-week visa extensions took four days to get, which wasn’t really worth it, so we decided to simply overstay and pay the fine when we left.

A day was spent in the dusty and totally enchanting Kabul bazaar, watching absolutely medieval things like the water delivery—it comes in goatskins. Then it was off along the Mazar road, a well-surfaced and Russian-built tar highway to the USSR border. After about 100km, we turned off onto the 160km gravel track to Bamian.

The track winds through the Koh-e-Baba mountains, with some breathtaking gorges and blasted, lonely plateaux on the way. I was a bit too keen and encountered a minibus as I was taking a corner on the wrong side of the road. Result, one dropped bike with twisted forks. We straightened them by the roadside, watched by a trio of goatherds, and not long afterwards I had another flat tyre. But, let me add, none of this spoilt the ride for us.

A young teacher invited us in for a cup of tea and we discussed politics without more than three words in common, except for proper names. He was in favour of the Communist revolution (“kommunis [thumbs up]”) which had just taken place—the first of three which culminated in the Russian takeover two years later—but he was violently anti-Russian.

I wonder what he’s doing now…. Our landlord in Kabul had warned us to make sure that everyone knew we weren’t Russians. Otherwise – he mimicked cutting his throat – we would wake up dead. The teacher more or less confirmed this for us.

Bamian, which is nearly three thousand metres high, was cool and quiet. We moved in at the Marco Polo Motel—the owner insisted that the man himself had stayed there but admitted he didn’t know in which room—and went off to inspect the magnificent 50 metre high statue of Buddha. This was carved out of the rock in the fourth century, when the monastery here had thousands of monks.

Genghis Khan chopped its face off some 800 years later. Genghis also destroyed the old city of Bamian, now an eerie collection of ruins on a hilltop called the City of Noise. They remember the Great Khan well up here in Afghanistan, if none too kindly. His worst act, one of the guides told us, was not to kill practically everybody but to destroy the qanats, the underground irrigation water supply.

The Ayar Valley, around the new Bamian, is an oasis of fertility in the grim mountains, kept green by irrigation water brought many kilometres from the melting snows by more modern techniques. Tourism has done its work, unfortunately; the children greet strangers with ‘Hello, paise’. Paise is the local word for—money.

We looked at the Red City on the way back. This is another ruined hilltop town, built of red mud and now melting down the cliffs in the infrequent rains. Then, on the road again, I did something very foolish.

Thinking I had been seen by the driver, I made to overtake a truck on the right. Just as I was level with it, the driver pulled over and inadvertently (I presume) ran me off the road. I went down a ten-metre forty-five degree embankment, weaving my way through huge boulder, into a field, where I stopped the bike and shook for a while.

Back in Kabul, we couldn’t believe ourselves in the mirror. We were covered in a fine, grey dust and looked about 90 years old. A shower soon fixed that, but at a price. The Kabul water supply also comes straight off the melting snows, and you step out of the shower blue with cold. Still, as everyone says, it’s very refreshing.

The next day, we had cholera booster injections before departing. The clinic was in an unmarked flat in a concrete block on the fringe of town, which was a bit of a worry, but we had been warned and had brought our own, new needles. We donated them after the injections, which went over very well.

The Kandahar road is dull, but the surface is good. We had intended to stop in Ghazni, but the government hotel had no water and the alternatives were dirty and expensive, so we pushed on to Kelat. Along the way we saw an Afghan hound herding some sheep, the only time I’ve ever seen one of these beasts at work.

Further on a small boy thought he’d impress his friends by throwing a rock at me. Now I don’t think this sort of thing is a good idea at all, so I turned around to go back and point out the error of his ways. He took off across the fields, running for all he was worth, and lost his cap, his satchel and the respect of his friends all at the same time.

Next week it’s, ‘go to gaol, go directly to gaol’ but we don’t mind one bit.