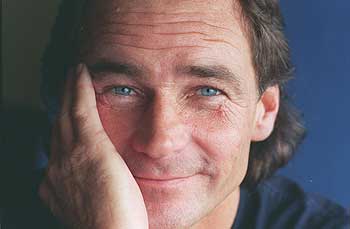

Barry Sheene Remembered

By Phil Hall

This time last week motorcycle race fans remembered the death of British motorcycling hero, Barry Sheene. Barry passed away on the 10th of March 2003 after a long battle with cancer.

This weekend Australia remembers Sheene via the Barry Sheene Festival of Speed at Sydney Motorsports Park.

Barry’s death was met with a world-wide outpouring of grief and emotion, the loveable Cockney having won the hearts of people (and not just motorcycling people) in every corner of the world.

Barry’s life and career has been exhaustively documented and there will be many readers who will be able to relate stories of their encounters with him as well.

Born into a well-off family in London in 1950 (Barry’s father, Frank, was the resident engineer at the Royal College of Surgeons), Barry grew up within reach of the famous Bow Bells and so was your classic Cockney. As a young man he worked at various lowly trades but his heart belonged to motorcycling and there are pictures of him as a very young man “helping” his dad with his dad’s bikes at various race meetings.

His dad had a passion for the Spanish Bultaco brand and it was on his dad’s 125 and 250 Bultacos that Barry did his early racing, starting in 1968. He was an instant winner, finishing 2nd in the British 125cc championship in 1969 behind Chas Mortimer (who would also go on to bigger things).

In 1970 he won the British 125cc title on the ex-Stuart Graham Suzuki twin, hardly a “privateer’s bike, and unwittingly started the “spoiled daddy’s boy” reputation that was to follow him through much of his early career. Spoiled he may have been but you had to have considerable talent and ability to ride one of those razors-edge bikes. In 1971, even though the Suzuki was showing its age, he almost did the unthinkable, finishing 2nd in the World Championship, injuries in other races preventing him from going one better.

He was signed by Yamaha for the 1972 season but incurred the displeasure of the Yamaha management by speaking out about the bike’s poor performance. Not long afterwards, the works-supported ride was taken off him and given to the Flying Finn, Jarno Saarinen.

In 1973 he was signed by Suzuki, a significant move in his career. Riding the TR750 triple, Sheene repaid Suzuki’s confidence by winning the newly created Formula 750 European championship. 1974 was to be an even more important year, though it probably wasn’t realised at the time. Suzuki introduced the square four RG500, a bike that would be instrumental in cementing his reputation as one of the greats but which would also prove to be the backbone of 500cc racing for many years to come as privateers on “customer” bikes continued to ride them and win races on them. Barry finished 6th in the World Championship that first year.

However, it was on the older TR750 that Sheene would achieve (unwanted) fame. Practising at Daytona for the upcoming 200, the tyre on the rear of Barry’s bike delaminated near the end of the banking, pitching the bike sideways and throwing him along the track. Graphic movie footage of the accident was flashed around the world as the story of Sheene’s miraculous escape from death was told. He had suffered horrific injuries but had survived and pictures of him sitting up in his hospital bed, smiling and smoking his Gauloises cigarette made him an instant hero. In an amazing feat of strength of will and body, Sheene was back racing in just 7 weeks.

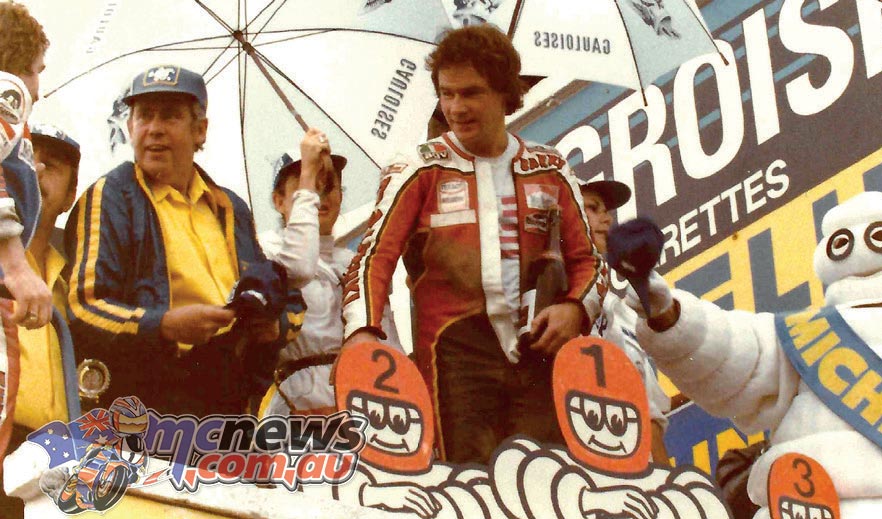

1976 and 1977 saw Sheene win the title both years on the RG. But, in 1978 the American, Kenny Roberts arrived in Europe and, backed by Yamaha’s huge resources and crewed by Australia’s Kel Carruthers, Roberts reeled off three 500cc titles in a row, 78-79-80. Sheene fought hard, his British GP battle with Roberts in 1979 being regarded by many as one of the greatest grands prix ever, but Suzuki was struggling to match Yamaha’s technology and it was no surprise when Sheene left the team in 1979 citing poor bike performance and favouritism within the team as his reasons.

Barry signed for Yamaha and soon started receiving factory support. He was competitive with Roberts on ostensibly equal machinery but Italy’s Marco Lucchinelli won the title, ironically, on a Suzuki. Barry was involved in another horrible crash at Silverstone in 1982 and it was no surprise that he announced his retirement in 1984. He remained (until 2015) as the last Briton to win a World Championship, a period of 38 years.

Sheene couldn’t stay away from motorsports and, amongst other things, competed in truck racing in Europe, sponsored by and driving the Dutch DAF brand, a company that had supported him in his motorcycling days.

But most of all we remember Barry for being the man who brought motorcycle road racing to the consciousness of the ordinary man. A flamboyant and outspoken character, his playboy lifestyle (like that of his F1 counterpart, James Hunt) made his name a common one throughout Britain and Europe. He parlayed his fame into numerous advertising and promotional opportunities and became extremely wealthy as a result. He would turn up to race meetings in a Rolls Royce with starlets and models hanging off each arm (one of whom, Stephanie McLean, became his wife, much to everyone’s amazement). You couldn’t open a newspaper back in the 70’s and early 80’s without seeing his face on some advertisement or other, such was his mass appeal.

It’s easy to see why. When he began his career, motorcycle road racing was virtually unknown to the ordinary Joe. Riders rode in plain black leathers and were seen (if they were seen at all) as occupying a nether world that had nothing to do with the swinging, hippie era that most young people knew. Sheene almost singlehandedly changed that perception and today’s grand prix superstars owe, in no small degree, their media presence and public profile, to the “out there” persona that began with Barry Sheene.

In the 1980’s, Barry and Stephanie moved to Australia, no doubt hoping that his many injuries would provoke less problems to him in the warm Queensland climate than they was doing in cold and inhospitable London. He quickly became involved with the local motorsports scene, moving easily into the role of “colour” commentator for Grand Prix telecasts, working with several local networks. His laconic style and wit saw him become a cult figure and his experience in other areas of racing apart from motorcycling saw him in demand for many different motorsports telecasts. Who can forget some of his witticisms? (insert Cockney accent as appropriate) “That bike is handling like an airport trolley.” “You don’t get no points in the First Aid tent.” And so forth.

Barry’s work with the Shell company and his association with touring car legend, Dick Johnson, also produced some of the funniest and most memorable advertisements we have seen on Australian TV. “A sock? What would I want a sock for?”

Search through Youtube and you’ll find dozens of Barry Sheene videos. They are well worth watching.

In July 2002 Barry was diagnosed with cancer and, some time later, it was revealed to the public that his fight was not going well. He succumbed to it on the 10th March 2003 and his loss was felt all over the world and especially here where we had come to see him as our adopted son. Survived by his wife, Stephanie and their two children, his name is still spoken of in reverenced tones, not just amongst the motorcycling fraternity but in the wider community as well.

The annual Barry Sheene Festival of Speed was created some years ago to perpetuate Barry’s memory and to remember not just his grand prix racing but his passion for historic racing. The timing of the event was chosen to be close to the time of Barry’s death and this year’s event, at Sydney’s Eastern Creek Raceway on the weekend of the 18th-20th March will be an especially poignant one with one of the special guests being Steve Parrish, a one-time team mate of Barry in the Texaco Suzuki team. No doubt Stavros will have a lot to say about Bazza when he is interviewed. Make sure that you don’t miss this event.

In a racing world where riders are seen to be increasingly dull and boring, it is good to remember the characters of the past, like Barry, who shook things up and brought life and humour to the sport.

R.I.P, Barry Sheene 1950-2003