Factory Turbocharged Motorcycles

With Phil Hall

In the continuing series of bikes that seemed like a good idea, but proved not to be in practice, so far we have looked at the Honda MVX250, the Yamaha XZ550 and the terrible TX twins, the TX500 and its 750 brother.

Until I wrote that I hadn’t noticed that all four of those bikes had the letter “X” in their model numbers. Could that be a clue? Did the manufacturers unconsciously doom these creations to failure by including this letter in the model designation? If that IS the case, our quartet of orphan bikes in this instalment could easily be confirmation of the idea, because this week I am going to look at FOUR orphans, one each from the major manufacturers and all of them being short-lived and unloved, and, sadly, all for the same reason.

I am talking, of course, about the Japanese manufacturers’ brief flirtation with turbocharged motorcycles. Turbocharging as a concept was by no means new by the time that the manufacturers started tinkering with it in the early 80’s. Indeed, the original concept of a turbocharger, a device that uses used exhaust gases to force the fuel/air mixture into the combustion chamber and so increase power, goes right back to the beginning of the 20th Century and the concept was played with by most companies involved in the manufacture of internal combustion engines right throughout that century.

Japanese motorcycle manufacturers, who all lived in a world of engineering leading edges, not only kept their eyes on what their competitors were doing but also on what was being done in the wider world of motors and motor sport. And it didn’t escape their notice (how COULD it have?) that the BMW engine in the 1982 Brabham Formula One car was a production based 1.5 litre four cylinder engine that, when the turbos were screwed up to the max for qualifying, was producing upwards of 1500 horsepower.

Downscale that to a motor, say half the size, drop the boost to manageable levels and surely you could have a mid-sized motorcycle that would produce monstrous amounts of horsepower without a significant weight penalty and you could have a bike that was king of the horsepower castle and a manufacturer that would vault itself to the top of the heap.

So it was not surprising, then that, despite the Big Four all having 1000cc-1100cc superbikes in their brochures already, these bikes dominating on the race track, the road and the balance sheets. They still decided to try their hand at building a turbocharged motorcycle. As with everything that the Japanese manufacturers did (and still do) the incentive was three-fold; capture the technological high ground, maintain their reputation as being leading edge builders and cover ever possible niche in an already crowded market place.

In the usual “monkey see – monkey do” scenario, Honda, Yamaha and Suzuki produced their turbo bikes in 1982-3. (one must not allow the other bloke to get a jump on you). Yamaha got a slight advantage by introducing the XJ650 Turbo in 1982. An oddity right from the beginning it was based on a less-than-spec chassis and used carburettors rather than fuel injection in the engine. The engine was both air AND oil cooled (Suzuki no doubt took note of this around 10 years later) and flirted with overheating issues. Add to this the fact that the styling was awkward to say the least, it is no surprise that it lasted just two years in the catalogue before being quietly discontinued. It produced a claimed 90bhp, not bad for a 650cc engine, but less than the 1000’s were producing and in a considerably more complex package. It wasn’t a great handler either so prospective buyers were understandably cautious.

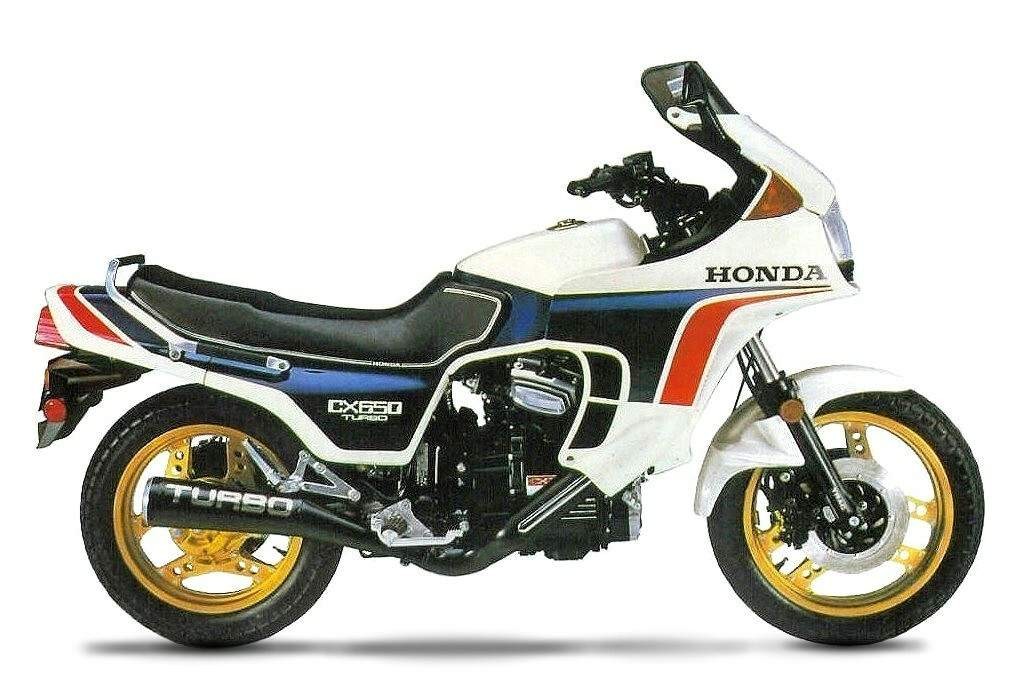

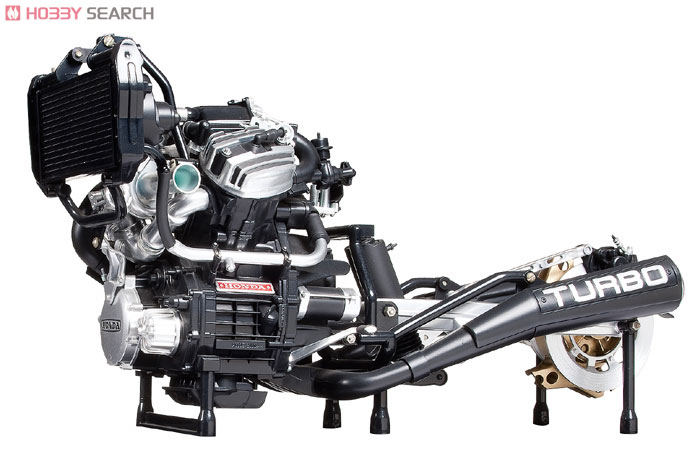

At the same time, Honda produced the CX500 turbo. Based on the curious CX500 with its “let’s make a Guzzi but let’s not,” V-Twin design, the Honda had the smallest engine and the lowest horsepower of the four (82bhp). It was fitted with what was thought to be an unnecessarily complex fuel injection system and the whole thing was wrapped in amazingly swoopy “look at me” bodywork.

The word “Turbo” was emblazoned in large letters on at least FIVE parts of the CX500 body to ensure that everyone knew exactly what it was. In 1983 the engine was enlarged to 650cc and the power raised to 100bhp. It lasted two years in the catalogue before also being discontinued.

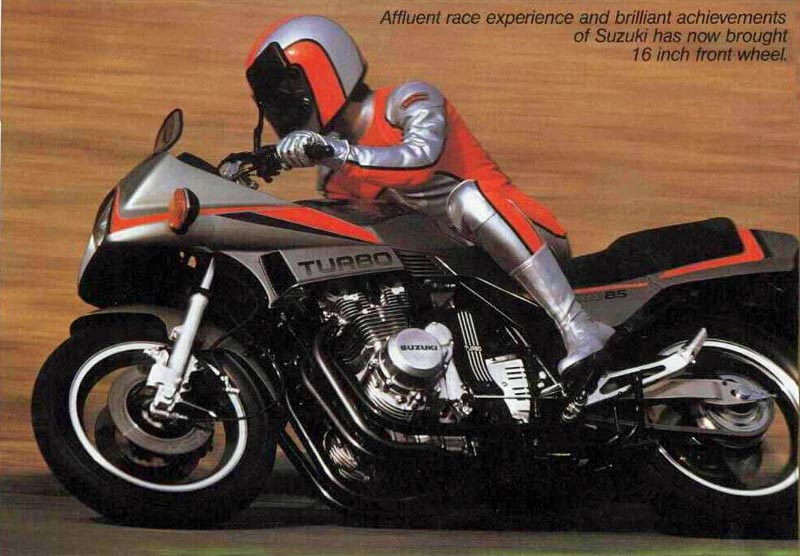

Suzuki was next, in 1983. The XN85 Suzuki was arguably the best styled of the bunch. Boasting a chassis that was carried over into the GS750ES of 1984, it handled well, produced 85bhp from its 673cc engine and turned outstanding times in the quarter for its capacity. Produced in very small quantities, it was a great package if one discounted the deficiencies of the turbo side of the equation. Despite its almost total lack of impact in the marketplace, the XN remained a catalogue model until 1988.

Kawasaki arrived late and, just as its caution enabled its Z1 to trump Honda’s 750/4 some 10 years earlier, it produced by far and away the best of the turbo quartet. The GPZ750 Turbo was fabulously styled and over-engineered as Kawasakis always were and it was also the most powerful and the fastest. 112bhp easily exceeded the output of the competitors’ bikes and it sold well. The engine was easily modified and could be pushed to around 200bhp, an amazing figure in 1984. Unsurprisingly, the GPZ probably killed more riders than the other three bikes put together but, having said that, it also out-sold the other three by a considerable margin. For all of its innovation, however the model only lasted a year, effectively being killed off by a similar but much more complete bike from the very same factory, the iconic GPZ900.

And so closed the short, but fascinating era of the turbo bikes. What went wrong? Well, a number of things, some technical and some practical. For a start, the turbo bikes were grossly more expensive to BUY than their normally aspirated cousins. They were much more complex and so greatly more expensive to service. Insurance premiums were FEROCIOUS and this was a huge discouragement to prospective owners. They appealed to the “early adopters” but, as often is the case, the early adopters paid dearly for their passion for living on the technological leading edge.

Turbo bikes never solved the issues of complexity, cooling and, most importantly, the dreaded turbo “lag”. Unless you had the bike up in the high rev range, your turbo 650 was slower than a normally aspirated bike of the same capacity. Once the turbo kicked in, you waltzed away but, by that stage, you had reached the next set of traffic lights and the whole horrid scenario was played out again. Added to this, your turbo 650 was heavier than a “normal” one and was fitted with the same suspension. So, once you reached the twisties, the combination of you being out of the boost when you needed it to be IN, and IN boost when you needed to be OUT of it, meant that your normally aspirated mate was at the top of the hill and was off the bike, inside ordering his coffee by the time you arrived. In the real world, the turbo was not only NOT an advantage, it was actually a disadvantage.

AND, while you wrestled with trying to convince yourself that your 650 turbo bike was better than your mate’s GSX1100/CB1100R , the manufacturers that had BUILT your technological marvel had, themselves, moved on, producing bikes that were progressively better and better than the one you were riding.

And so the turbo bubble burst. Bikes for which eager riders had paid an exorbitant premium to possess languished on the used bike market for a fraction of their original purchase price before being sold, on and on to oblivion or, worse still, were scrapped at zero value. Today they are collector’s items, commanding prices that exceed their original RRP, IF YOU CAN FIND ONE.

Oh, and that “X”? Well, to nobody’s surprise, three of the four have an “X” in their model designation. Perhaps I should rename my series, “The X Files” ☺

The previous failures notwithstanding, the technology is now available for all the original shortcomings to be addressed and easily overcome, so are we on the cusp of a new era for factory turbocharged motorcycles..?

A quick technical note here for the uninitiated. Turbochargers and superchargers (as seen in the latest supercharged H2 Kawasaki) are not the same thing. A turbo uses exhaust gases to drive a turbine impellor, which then pressurises the cylinder, while a supercharger uses a pump that is driven mechanically from the engine, generally via a belt or gears driven off the crankshaft, and thus its speed is determined by the speed of the crankshaft.

As such, a supercharger produces more power and boost, the higher the engine revs, although in today’s modern applications that boost can be delivered anywhere and is more often used to boost low and mid-range torque, with the boost then being bled off as the revs rise, normally to protect the driveline from failure under high boost, high rpm applications.

While the early turbo era was characterised by turbo lag, with a sudden rush of power as the exhaust gases drove the turbine impellor up to speed, again, modern engine management systems can pretty much put the boost exactly where it is needed to produce the desired torque curve. In the early turbocharged bikes featured here that was not the case, but today the technology is available to produce turbocharged motorcycles with excellent throttle response and a linear power delivery, and a lot of manufacturers are exploring forced induction for new models now on the drawing board and in prototype phases.