Harley-Davidson XR750

Celebrating 50 Years of the Harley-Davidson XR750

By Chris Martin

If forced to condense the long, illustrious history of the Grand National Championship into a single mental image, what would jump into your head?

Would you drift back to the mid-’70s and envision an epic showdown featuring legendary champions Jay Springsteen, Kenny Roberts, and Gary Scott?

Or maybe the mid-’80s, when superstars Ricky Graham and Bubba Shobert went to war with double champ Randy Goss and an up-and-coming Scott Parker?

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

For many — perhaps even most — it would have to be the mid-’90s, after Parker had long since established himself as the most successful rider in series history, but then found himself pushed to the very brink by fellow GOAT candidate Chris Carr?

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

But whatever era you chose, it’s almost unavoidable that mental image would prominently feature Harley-Davidson’s iconic XR750 — just as it did in all of the examples provided above.

The overwhelming mindshare the XR750 has acquired in dirt track circles is backed in full by the numbers, which are staggering… numbers that should not be possible in a technologically-driven endeavor such as motorsport.

We’re talking incomprensible, ridiculous numbers… 37 Grand National Championships and 502 premier-class Main Event victories for starters.

But for all the sensational statistics, one number stands out at this moment: 50.

The XR750 was introduced into Grand National Championship competition in 1970, a full half-century ago. And as the XR did its very best to practice social distancing from the competition over the decades, this seems like the ideal time to celebrate an industry-defining machine in a multi-part feature.

“It is an absolutely remarkable achievement for how long the XR750 dominated the AMA field… earning the description of being the ‘most successful racebike of all time’ in the process,” said Jon Bekefy, Harley-Davidson’s GM of Global Brand Marketing. “That dynasty is crazy for any motorsports machine, two wheels or four.”

How is it even possible that a racebike, of all things, could not only remain competitive, but dominant for such a vast stretch of time?

It’s difficult to grasp, let alone explain, but it’s as if the stars aligned… and then stayed aligned for nearly five decades. The XR750’s irreplicable record is the result of an astutely engineered platform, continually developed in both radical and subtle ways, applied to a sport where traction is imperfect by definition, and mastered by multiple generations of the most accomplished racers and tuners two-wheeled sport has ever known.

The list of all time greats already inducted into the AMA Hall of Fame whose legends were built in concert with the XR750’s runs into the double digits — names like O’Brien, Werner, Springsteen, Parker, Carr, Brelsford, Scott, Eklund, and Goss. And the future Hall of Fame candidates who earned Grand National Championships on the machine are destined to further expand that list — names like Kopp, Coolbeth, Johnson, Mees, and Baker.

Chief among those masters is the aforementioned Scott Parker, who is arguably more closely associated with the XR750 than any other rider. During his time, Parker earned a jaw-dropping nine Grand National Championships and 94 Main Event wins (nearly all of them on the XR750).

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

To add some perspective to the astounding longevity of the XR750, consider that following the conclusion of a 20-year GNC career, Parker came out of retirement 20 years ago to win the Springfield Mile one last time. Now consider that by the time he first threw a leg over the XR750, it was already considered a legendary machine with five national titles stacked in its corner.

Even as the decades have ticked along, Parker still has vivid memories of his first time on the XR. “The first time I got to ride one is one of my greatest memories. My buddy flew down and picked one up on an airplane and brought it back. I just couldn’t wait to ride it. It had so much more horsepower than anything I had ever ridden. To get on that thing — and just the way it delivered the horsepower… Wow!

“I was more of a cushion rider, and you just get it in a corner and you could just give it the gas. It would turn the rear wheel and start putting traction down to the ground and down the straightaway you’d go. The first time I got on it, I remember going, ‘Oh my gosh, this thing is badass.’”

The AFT paddock is lined with riders with similar tales of their anticipation of riding an XR750 for the first time and then having it meet, if not exceed, all the hype.

2000 Grand National Champion Joe Kopp, who happens to be the same age as the XR750, said, “I remember… Gosh… It was probably ’90 or ’91. I was new to a twin — I had ridden a Triumph a little bit but definitely never an XR750.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

“That was the one everyone wanted to be on. It was just kinda the bike you dreamed of. And when I finally got to ride one… ‘Holy Smokes!’ I just couldn’t believe I was on one, and how it put the power to the ground compared to all the bikes I had ridden before that.

“I was working with Vance & Hines and Harley a couple years ago (developing the XG750R), and with Indian (developing the FTR750), and the XR750 was still their benchmark. Even though the Indian is doing really well, they still sometimes look for ideas from the XR750. It’s pretty crazy to think it was designed and built 50 years ago.”

That same sort of awe is shared by the sport’s fanbase at large. Bekefy, who worked at Ducati,

IMZ Ural, Mission Motors, Alta Motors, and Triumph prior to taking his current position at H-D, still views the XR750 through the eyes of a fan.

“When I was a young kid from San Francisco, Harley-Davidson was two things: Easy Rider and flat track. I knew all these names; Parker, Springer, and for sure Carr. Norcal has a deep flat track legacy regardless of brand or rider, but those names I knew like I knew the States’ names.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

“It’s a legacy alive in the pits of AFT racing today. It’s awesome to hear stories of how the XR750 has played a pivotal role in the racing community. From late-night wrench sessions to the checkered flag, so many people have fond memories of the bike, and that continues to stick with me.”

While not intentional, it’s apt Bekefy should mention Easy Rider; the XR750’s generations-spanning success is due in no small part to the fact that, for all its power, it’s a famously easy-riding machine, albeit one far removed from the “Captain America” and “Billy Bike” H-D Hydra-Glide choppers featured in the film.

Kopp explained, “I see a fair amount of young kids who hop on an XR750 for the first time and do pretty darn good. I just think it generally puts the power to the ground and is such a super easy bike to ride… Big flywheels, doesn’t rev up all that quick…

“Actually, to me, as a racer, it could be kinda frustrating when we went to an easy track — like a real round, circle track that wasn’t real technical. When we were all on XR750s, everybody was so dang fast. Instead of five or six guys up front, it was 15. I was like, ‘Oh s—… here’s another one of those races.”

Bill Werner had a hand in developing the original cast-iron XR750 first introduced in 1970, and then played a critical role in transforming it into the all-dominant aluminum XR750 a couple years after that. As a race tuner of XR750s, he’s credited with 13 Grand National Championships and 130 Main Event wins. In other words, he knows its secrets better than anyone.

And one of those secrets is the fact that riders tuned themselves to the XR750 as much as the bike was tuned to them. Due to its rider-friendly nature, decades of racers built their styles around its strengths, creating a feedback loop of championship-winning glory.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

Werner said, “So many riders, their internal clocks — their skillsets — revolved around the unique idiosyncrasies of that motorcycle. So when they jumped on something else that was foreign to them, that accelerated differently… like the Kawasakis and stuff that had lighter flywheel mass and maybe more horsepower… Some guys found it difficult to adapt to something different from what they knew.”

Incredibly, even while celebrating the 50th anniversary of the XR750, it’s not dead yet, even if the factory Harley-Davidson squad moved on with the XG750R a few years back.

The XR750 reigned supreme at the very pinnacle of the sport as recently as 2017, when Jeffrey Carver Jr. dominated the Lone Star Half-Mile, leaving a stacked field of Indian FTR750s, Kawasaki Ninja 650s, H-D XG750Rs, and Yamaha FZ-07s in his wake.

And just last season, Danny Eslick raced his way into the Main and snared a handful of championship points on an XR750 at the Lima Half-Mile.

Reflecting on its modern-day success, Parker said, “You can look at the lap times over the decades. Bryan Smith only recently took one of the records I had at Springfield. All these years, the XR has been… Some of these other bikes may be faster, but it just delivers the power and the traction to the ground and that’s what really matters.”

Kopp took it a step further. “I’ve got a really good, fresh one, sitting inside my home. If I ever dig it off the shelf for my kid, I would update the suspension, but other than that, she’s ready to go. I think they’re still good.

“I’m getting excited talking about it… This is making me want to go race again.”

It’s a definitional reality of racing that you can’t win by sitting in place. For the legendary Harley-Davidson XR750, that was every bit as true in the race shops as it was on the race tracks.

The basic platform has remained recognizable as the genuine article throughout its existence; the iconic XR750 name is not merely a common designation shared by an endless string of complete technical overhauls and reinventions as one might find in MotoGP.

That said, winning an average of ten-plus races per season over the span of a half-century required non-stop evolutionary innovations in order to extract every last molecule of performance from that basic platform.

Nine-time Grand National Champion Scott Parker said, “Think about it: The thing was designed 50 years ago and was competitive up until… I think people are still riding them from time to time today. They could still win races, that’s the cool thing about it.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

“Here you’ve got a motorcycle that is 50 years old and even through all the stages that it’s gone through to get here, there are some parts that have been there the whole 50 years, which is amazing.

“They kept trying to improve it and improve it and improve it, but it still had the same basic design… They just kept innovating, getting a tad bit better constantly, and here it is, still competitive all these years later.”

Ironically, the most successful racebike of all time is one Harley-Davidson likely would have preferred not to have to build, only designing it when its hand was forced.

Afterall, H-D already had its generational flat track machine in the flathead KR750 — at least up until it didn’t. Introduced a year before the Grand National Championship was first organized as a series in 1954, the KR750 immediately proved the GNC’s dominant mount and didn’t relinquish the throne for years.

The KR stormed to 13 of 16 Grand National Championship titles from ‘54-’69 while racking up a mammoth tally of race wins along the way, including every single one available in 1956.

But the rulebook was updated in 1969, eliminating the 250cc displacement advantage for sidevalve machines that the KR750 had previously enjoyed. As a result, the gates were kicked down by Harley-Davidson’s more modern overhead valve-armed British rivals and the writing was on the wall.

Gene Romero won the GNC on a Triumph in 1970 followed by Dick Mann aboard a BSA in 1971.

Under factory race manager Dick O’Brien’s watch, Harley-Davidson moved quickly to adapt to the new regulations, Frankensteining the original “Iron XR750” from parts taken from the 883cc Sportster XLR outlaw racebike. In order to meet the 750cc displacement limit, the stroke was decreased while its bore was increased, but the pushrod V-Twin retained the XLR’s cast-iron head and cylinders.

13-time Grand National Championship-winning tuner Bill Werner was already employed in Harley-Davidson’s race shop at the time, kick-starting his long association with the XR750 from its nascent beginnings.

“I don’t think there’s anyone who’s been around an XR750 more than Bill,” Parker said. “He was there from the very beginning and eat, slept, and drank that bike. He loved them.”

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

Werner said, “Yeah, I was privileged to be there at its inception and through all its development to its peak era. I was there right for the transition from the flatheads to the XRs, from the cast-iron XRs through the Aluminum XR — engine development, frame development, and all that sort of stuff. Not only was it a thrill, but it’s something you can look back at and say it’s part of your legacy.”

Reflecting on the initial task of bringing the original Iron XR to life for the 1970 season, Werner admitted, “It was a huge process. We had failures converting an 883 Sportster into a 750. We had to destroke it and we had flywheel issues. And then after we got those solved, we had to deal with the things overheating because they made good horsepower but they’d get too hot. We had all kinds of challenges to cooling them off.

“I had the sole task of converting them to dual carburetor kits. I welded up all the heads on the factory conversions, taking a front head and making two front heads and a dual-carb conversion out of it. I had to plug an exhaust port and move it from one side to the other to make the rear head.

“And I spent the better part of a year welding up all the heads, brazing them all up, and sticking them in 55 gallon drums of powdered asbestos to cool for two days because they’d crack through the valve guides if you didn’t do that.”

Harley-Davidson fielded the Iron XR750s for just two seasons while an alloy-based rethink was being readied. While not remembered nearly as fondly as the more refined XR750 to come due to performance and reliability issues, history has given it something of a bum rap.

Mert Lawwill debuted the Iron XR in winning fashion in a non-sanctioned outlaw race at Ascot, and then scored its first official GNC race victory weeks later, still early in the ‘70 season, at the Cumberland Half-Mile. It went on to rack up a combined ten victories during the 1970-1971 Grand National Championship seasons, providing clear evidence that Harley’s KR successor was destined to become a force in its own right from the start.

Werner said, “The cast-iron XR actually won races in its first year. We had failures and it didn’t win the championship, but it won races.

“We ultimately knew it was a stop-gap effort, and we were going to transition to the Aluminum XR. I got in on the ground floor of that too and was part of the dyno testing.”

The transition was more than just a simple elemental matter as the nickname change suggests. Harley-Davidson’s race department took full advantage of its second chance to introduce a new-generation racebike and leaned heavily on the lessons learned by the iron machine.

“Some of the things we learned in the flywheel area we incorporated into the ’72 Aluminum XR, even though it had a different bore and stroke and all that,” Werner explained. “We changed the lubrication system from a timed breather system to a mini-sump system. We changed the cam shaft diameters because the ball bearings closest to the crankcase would fail; we converted them and put in needle bearings on the crankshaft side.

“Cam development was huge too because the engines were capable of more RPM — they had a bigger bore and shorter stroke than the cast-iron XR. The first heads had ports about the size of your finger, and we had to do all the cylinder flow work… You’re better off casting them with too much material because you can’t put it in and you can always take it out.”

The intensive and radical (re)development paid immediate benefits. With Mark Brelsford at the controls, the Aluminum XR finished as race runner-up in its national debut at the Colorado Springs Mile, won in its second race at the Louisville Half-Mile, and earned the Grand National Championship in its very first attempt.

The rest was record-book obliterating history, as the Aluminum XR750 would go on to win 492 of the XR’s ridiculous 502 premier-class race wins, along with its insane tally of 37 GNCs.

Of course, in order to achieve those results, continual development was required the entire way.

When asked, Werner rattled off various updates, stream-of-consciousness style. “The ports evolved from round to oval over time. The rocker shafts got changed from a clamp-type arrangement that held the adjustment to a nut-type arrangement that tightened it up. The shaft diameters changed. The RPM went up. The spring rates went up. We changed from steel valves to titanium valves.

“The engines used to start at maybe 7800 to 8000 rpm max, and by the end of its transition we were turning at 9500 rpm. We went from quarter-speed oil pumps to half-speed oil pumps to circulate more oil over the engine to cool it better. We went from aluminum cylinders with cast-iron liners to all-aluminum cylinders to nickel-plated aluminum cylinders that were lighter and cooled better.”

Over the years, all of those small improvements added up (and up… and up).

Parker said, “The first XR I got on had like 70-odd horsepower. By the time I was done, it was somewhere around 105. Over just the time that I rode one, that’s the difference we’re talking about.”

But not all of the development work was dedicated to a never-ending quest for more power, nor were they all so small and incremental. A full decade before Honda turned the Grand Prix world on its head with the introduction of the “big-bang” firing order for the NSR500 in 1992, H-D experimented with the same concept and for the same reason — seeking both maximum traction and a more rider-friendly mount.

Werner said, “One of the things we did on the XR was what they called “twingling.” The standard XR fires a 157.5-202.5 degrees… It’s a 45-degree V-Twin — one cylinder fires when the other one is on the exhaust stroke. It’s not symmetrical — it can’t be because it’s a 45, single crank.

“I thought, what if I fired them 45 degrees apart, just 45? All you have to do is turn two camshafts 180 degrees, turn one of the ignition shafts 180 degrees, and it will fire 45 degrees apart.

“It sounded like a big single. Some guys loved it, and some guys couldn’t tell much difference. It depended on the type of rider you were. If you were a real brave, aggressive guy… not that big of a deal.

“While we were first testing them, I was with (three-time Grand National Champion) Jay Springsteen at a dragstrip in California. I ran the “Twingle” down the racetrack, and he asked how it felt. I told him it felt butt-slow. He said, ‘Well, let’s compare it to the other bike.’ So we drag-raced them side-by-side and they were dead equal. We switched bikes and they were still dead equal.

“When you got on the Twingle, the sensation of speed was lessened. You didn’t hear that rush of high RPM. It’s like the difference between riding a single and a twin. So timid riders loved the Twingles because they could go faster than their normal intestinal fortitude would have let them.”

Whether it was actually down to rider temperament or something more tangibly mechanical, the Twingles proved to be serious weapons on more slippery surfaces and remained a popular choice of top riders until they were ultimately prohibited from competition in 2006.

A crucial difference motorcycle sport has long lorded over its four-wheeled counterpart — and continues to even in today’s electronics age — is the simple fact that on a bike the human behind the controls remains the ultimate factor determining wins and losses.

For all the decades of developmental work and mechanical black magic behind it, there’s no denying that the historic success of Harley-Davidson’s XR750 is also intrinsically tied to the heroics of a select group of otherworldly riders.

As covered previously, when presented with some novel rulebook hurdles in the late ‘60s, H-D responded with the creation of the original Iron XR750 in 1970 and then further iterated on that design with the superior Aluminum XR750, released just two years later.

The result of that engineering exercise was a well-balanced, rider-friendly package that provided a wide range of flat track artists an outstanding brush with which to paint their masterpieces on oval canvases of dirt and clay.

The ‘72 machine was so good, in fact, it won the Grand National Championship in its first go and positioned itself as an unbeatable machine going forward.

However, as formidable as the XR and its rider line-up may have been, Harley-Davidson was beaten to the throne in ‘73 and ‘74, despite the fact that a full ten different riders claimed at least one victory on the XR750 through the end of that season — each one an eventual AMA Motorcycle Hall of Famer, save Dave Sehl, who himself was inducted into the Canadian Motorcycle Hall of Fame.

But even with all of those future HoFers in its corner, H-D and the XR750 were ultimately outdone and outclassed by a truly transcendent talent in Kenny Roberts, despite the Californian being significantly outgunned on his Yamaha XS750.

To overcome Roberts, Harley needed its own ‘King.’ It might have already had one in Gary Scott, who actually beat Roberts for Rookie of the Year honors in ‘72 and then finished as runner-up to him in ‘73.

Photo: NASCAR Archives

H-D signed Scott to the factory team in ‘74. And after notching up a second straight second-place season, he finally delivered Harley another Grand National Championship in 1975… before promptly leaving the squad in a contract dispute following the season.

Desperate to replace him with the most spectacular rider they could unearth — one who could go head-to-head with Roberts and Scott and somehow come out on top — Harley-Davidson turned to a flashy 18-year-old named Jay Springsteen who had just earned Rookie of the Year honors.

Bill Werner, who was fresh of earning his first GNC title as a mechanic, knew that things were going to be quite different within minutes of the first official meeting with ‘Springer’ ahead of the ‘76 season.

Photo: NASCAR Archives

“(Team manager Dick) O’Brien said, ‘Hey we’re going to have Springsteen come over to set up the bike for the Houston TT.’ Springer came into the shop and said, ‘Where’s the bike?’ I asked him if he wanted the rear brake on the right or the left.

And he said, ‘If you put it on the left, I’ll step on it over there, and if you put it on the right, I’ll step on it over there.’

“‘What about the handlebars?’

“‘Wherever they are is where I’ll put my hands.’

“And within two minutes he got on it and said, ‘Yeah, that’ll be okay.’

“Gary Scott was very, very finicky. I was used to working with a guy who had me taking a quarter inch of foam out of the seat because he didn’t feel comfortable on it. I went into O’Brien’s office and told him we were done setting up the bike, and he said, ‘What do you mean you’re done?’

“‘He said he’ll ride it just the way it is, and that’s fine.’”

It was ‘fine’ by even the most outlandish boundaries of the definition.

Springsteen defeated Roberts and Scott to claim the title in ‘76 and then again in ‘77. And for good measure, he added a third straight Grand National Championship to his résumé in 1978.

Springsteen established himself as the winningest rider in series’ history relatively early in his career and continued to build on that tally all the way into the new millennium. To this day, his 43 victories have only been eclipsed by three riders.

Werner said, “Jay was just a huge natural talent. He didn’t jog or lift weights. He didn’t do any of that stuff. He rode motorcycles in the woods and did normal stuff, but he didn’t have a specific diet or a trainer. And he was always amazed that other people couldn’t do what he did.

“He said, ‘Come on, this isn’t that hard.’ And I was like, ‘You’re only an inch away from the fence all the time, doesn’t that scare you?’ ‘Nah. As long as you don’t hit the fence, you’re okay.’

“I remember at Toledo, Kenny Roberts had set the fast time in time trials, and then Jay went out and went faster. When Jay was coming into the pits, Kenny sat there watching and said, ‘Springer — I’m kind of curious. What’s your shut-off point going into Three? What’s your mark?’

“Jay said, “Shut-off point? I just hold it wide open and try not to crash.’

“Roberts walked away and said, ‘This guy is nuts…’

“He just ran it in there until the front end pushed and then the rear-end came around and he saved it and stayed on the gas. There was no plan, just stay on the gas.

“Jay did refine his skills over time, and he got a little more artful and realized that not every track was just a wide-open thing. He got better on grooves and whatnot, but in his early years his mentality was that the fastest way around was holding it wide open and trying not to crash.”

Guts clearly weren’t an issue for Springsteen, which makes it a sad irony that his stomach actually was his Achilles heel. Over the next few seasons, Springer missed numerous Main Events due to a mysterious ailment that doctors attributed to excessive acid flow brought about by nerves.

That opened the door for others to rush in, and the next five Grand National Championships went to four other riders armed with XR750s (again, each one of them a future Hall of Famer and with no overlap to the ten already referenced).

Despite the XR750’s continued success, Harley-Davidson again found itself searching for a handpicked successor who could rack up victories and string together multiple GNCs the way Springsteen had in the late ‘70s.

And again, it turned to a young rider bursting with talent in ‘79 Rookie of the Year Scott Parker, drafting him up to the works H-D squad midway through the ‘81 season.

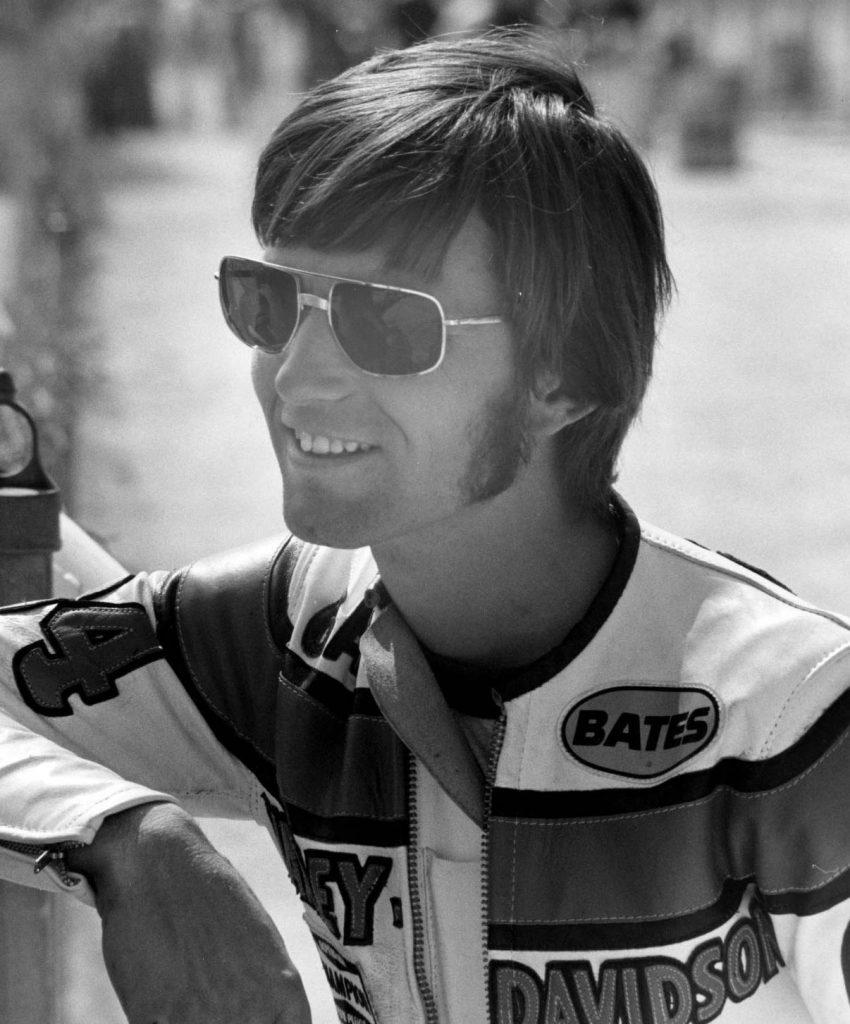

Parker’s swagger and style are unmistakable on the racetrack.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

However, the early- and mid-’80s were a tumultuous time for Harley-Davidson in general, putting the factory race effort in dire jeopardy. It was extremely bad timing, as Honda was preparing to introduce a game changer.

Honda followed Yamaha’s playbook to beat Harley-Davidson by hiring a pair of ascending superstars in ‘82 GNC Ricky Graham and the ultra-talented Bubba Shobert, and then took it a full-step further by following Harley’s own playbook on the machinery side of the equation.

After enjoying only limited success with its CX500-based NS750 flat track machine in 1981 and 1982, Honda closely studied the basic design of the XR750 and then added some modern HRC touches to it.

Like the XR750, Honda’s new RS750 featured a four-speed 45-degree V-Twin (right down to identical 79.5mm x 75.5mm bore and stroke numbers) but also four-valves per cylinder and overhead cams as opposed to two valves and a pushrod design.

“Honda was smart,” Werner said. “They bought a couple XRs, and they took them apart because the XRs worked so well. They duplicated the flywheel mass and the V-Twin configuration, but they were pretty sure they didn’t want pushrods or two-valves. So essentially, it had a lot of the plus characteristics of the XR with none of the minuses.

“It didn’t really make any more power than an XR, it just made more RPM. So what’s the advantage? If an XR comes off the corner at six grand and the Honda comes off at seven grand and the terminal velocity is the same, they start up a thousand RPM on the band and just have more power on tap due to the RPM difference.”

The RS750 was tested in action during the ‘83 season (and even won the Du Quoin Mile courtesy of Hank Scott) before being fully unleashed on the series in 1984 with Graham and Shobert at the controls.

It proceeded to rip off four successive Grand National Championships.

Meanwhile, Harley’s full factory effort had been effectively mothballed with the race department reduced to just a single employee — Werner — whose job at that point primarily consisted of shipping out parts to privateer teams.

However, even if the factory H-D team no longer existed, Parker insisted on having factory-level talent building and wrenching his XR750.

Werner said, “In ’85, the factory disbanded its racing team and gave all their riders their equipment and told them to hire their own tuners and stuff like that. About one or two races into the season, Scott Parker called and said, ‘I’m not happy with the guy I hired. I want to hire you.’ And I told him I was working full time and couldn’t do that. And he said, ‘Well, I’d rather have you working on my bike four hours a day than the other guy 20.’

“I agreed to go to work for him, but Harley-Davidson management didn’t want it to happen. They told Scott, ‘Nope, your contract says we get to authorize anybody you hire to make sure they’re competent.’

“Scott took it to his attorney, and his attorney said to Harley, ‘You’re right. You have the authority to judge whether the guy is competent. And this guy has won four national championships. How can you say he’s not competent?’

“Harley tried to argue that I wouldn’t have the time to do the job correctly, but Scott’s attorney said, ‘That’s not what the contract says. The contract only says competent.’

“So reluctantly, they let me go to work for Scott, and I did it all at home.”

Parker enjoyed his finest campaign as a professional yet that season, including a massive win at the Indy Mile which finally halted Honda’s dominant streak of Mile victories that had stretched into the double digits.

He ended the season ranked third in points and followed that up with a runner-up showing the following year as he and Werner continued to seek out new ways to derail the Honda freight train.

Werner said, “The RS was just a better engine than what the XR was. But it had it quirks too. It hit so hard it burned up tires more than what the XR did.”

Restrictor plates were added to the equation in 1987. Most will tell you the move was done solely to undercut the inherent advantages of the RS750, but Werner argued the Honda’s one weakness, in part, brought the penalty upon itself.

“(Burning up tires) was one of the reasons the AMA instituted the restrictors. They wanted to slow everybody down. There were a couple races in particular where the top riders went right through their tires. Goodyear wasn’t about to make new tires for that small a market. They transitioned to Carlisle tires for a while that were harder, but they’d go through those tires too. They had to keep shortening races from 25 laps to 20 laps to 15 laps and pretty soon the competition committee said, ‘This is nuts. Why don’t we just slow everybody up? You don’t have to go 130 on the straights. Why not just 120?’ It hurt all engines about the same. Having them all close was the key.”

Parker came within seven points of dethroning Shobert in 1987.

If anything, the XR750 platform had been made stronger due to the lessons learned during the race program’s hiatus and Honda’s run of dominance. And just as Harley-Davidson amped its factory program back up to full bore, Honda was gearing down and looking to exit, frustrated with the new regulations that had been put into place.

Werner explained, “Before I brought the program back into Harley-Davidson, I worked with different vendors and developed different cam profiles and other things that made Scott’s bike, I think, better than everybody else’s.

“We had an advantage, and it wasn’t due to the factory giving me s— because they only reluctantly allowed me to do it at all. But rather, I had the freedom to go to any vendor I wanted because I was on my own working out of my own garage. And a lot of those things got transitioned to the official product when I ultimately got to work in the department fulltime and they hired back more staff and a manager and all that other stuff.”

Parker did finally overcome Shobert to end the Honda dynasty in 1988 while starting one of his own; he would go on to claim four consecutive Grand National Championships from ‘88-’91.

Parker currently holds the record for most career wins at 94.

Photo: NASCAR Archives

Ultimately, the challenge to Parker’s crown would come from within the throne room.

Harley-Davidson had learned to have a worthy heir in place. Just one year after Parker’s reign began, it found one in the gifted 1995 Rookie of the Year, Chris Carr.

Carr’s skillset was a bit different than Parker’s, which worked well in terms of making the factory XRs heavy favorites virtually every weekend, no matter the discipline, year after year.

Parker was the unquestioned maestro of the Mile; he raced the XR750 to an astonishing 55 Mile victories during the course of his career (more than twice as many as the current master of the form, Bryan Smith). Carr, meanwhile, was an unstoppable force at the TTs and the STs. And both riders were among the greatest Half-Milers the sport has ever seen.

Both styles worked equally well at racking up championship points. The next decade saw Parker and Carr engage in several of the greatest title fights in American Flat Track history.

Parker’s ‘91 title win over Carr came down to the tiebreaker, and then Carr struck back with his first Grand National Championship the following season, ending Parker’s run of four straight GNCs by just two points.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

Ricky Graham broke up the epic annual intra-team title fights with an amazing ‘93 season to give the RS750 one final run to glory, before Parker reclaimed the #1 plate in ‘94, this time by four points over Carr.

Carr was drafted into the factory Harley-Davidson AMA Superbike team in ‘95 and would focus the bulk of his efforts hustling the VR1000 around on pavement for the following three years. During that time, Parker continued to stack up titles, the last (his ninth) coming by a scant two-point margin over Carr in ‘98 upon his rival’s full-time return to dirt track racing.

By ‘99, Carr was running his own team, had Kenny Tolbert wrenching his XRs, and had rounded into an all-around dirt track master, Miles very much included. He scored a blowout title triumph in Parker’s farewell season, setting the stage for a run of six dominant GNCs from ‘99-’05. That string was broken up only by Joe Kopp’s 2000 Grand National Championship, earned while Carr was splitting his time winning the short-lived Formula USA National Dirt Track Championship.

Reflecting on the Parker-Carr years, Kopp said, “It was pretty wild. They had some really heated years right before I stepped in. I got in late in their battle, and then Chris and I got to have a lot of battles ourselves over the years. It was really neat to be a part of that. Any time that I got to race Scottie or Ricky or Chris… Gosh, it was a helluva race.

“I remember Scottie’s last Springfield in 2000. Even though I was credited as the winner at the Dallas Mile in ‘99, that race was red flagged and ended on lap nine. So in my mind, I didn’t have an official Mile win at that point and was still looking for my first. Will (Davis) got his first Mile win that Saturday there at Springfield, and I finished second. The next day, sure as s—, Scottie Parker is here — ‘Mr Springfield ’ — and he comes out of retirement and goes and wins the thing and I got second again. I was like, ‘Damn!’ Even though he had been retired for a year or whatever, it was just an honor to race with him in a situation like that.

“I wish I could have been in the middle of more Scottie and Chris battles, but I had my fair share. I got frustrated enough in the few that I was in.”

Carr continued to race into the 2010s, setting the bar extremely high during what was the formative era for a number of the today’s crop of AFT SuperTwins aces.

Ultimately, the three titans of the XR750 — Jay Springsteen, Scott Parker, and Chris Carr — combined to score a nearly unthinkable 183 GNC Main Event victories and 19 Grand National Championships on the iconic machine.

Previously we covered the genesis and development of Harley-Davidson’s XR750, as well as the outsized contributions to its glorious history made by three titanic talents in Jay Springsteen, Scott Parker and Chris Carr.

However, while those stories of the XR span from the ‘60s into the new millennium and effectively defined the careers of perhaps the three greatest riders American Flat Track has ever known, it’d be a great disservice to the bike to suggest its history ends there.

In truth, the legacy of the XR750 transcends far beyond even those eras, heroes, and the sport of dirt track racing entirely.

To briefly address that last point first, it could be argued that no two-wheeled icon and their equipment have achieved the same sort of celebrity, and been etched so permanently into the public consciousness, as daredevil Evel Knievel and his fleet of red, white, and blue XR750s.

And the XR didn’t only succeed on dirt or in the air. Cal Rayborn was the hero of the ‘72 Transatlantic Match Races on a roadrace-spec Iron XR750 TT, and then gave the Aluminum XR its only two GNC roadrace victories later that year at Indianapolis Raceway Park and Laguna Seca.

Mark Brelsford actually earned the first (and only other) GNC roadrace win for the platform in ‘71 at Loudon on an Iron XR. A couple years later, Brelsford’s #1 Aluminum XR750 TT went up in flames (along with his hopes of defending the Grand National Championship) in a dramatic crash at Daytona International Speedway.

A decade later, that same destroyed bike was pulled from purgatory and re-forged into a pumped-up 1000cc XR-based racer that promptly won the Battle of the Twins race at Daytona with Springsteen at the controls.

If that wasn’t good enough, the resurrected machine was then dubbed “Lucifer’s Hammer,” wrenched by famed H-D tuner Don Tilley, and wielded by Gene Church. The pairing went on to claim the AMA BOTT crown for three years running from ‘84-’86.

But even when taking only the XR’s flat track accomplishments into consideration, there’s so much more to the story. While Springsteen, Parker, and Carr did combine for an astonishing 183 Main Event victories and 19 Grand National Championship, simple arithmetic tells you that still leaves an additional 319 wins and 18 GNCs on the docket.

Digging a bit deeper, 55 riders other than the Big Three won races on the XR750, and 11 of those 55 earned at least one Grand National Championship onboard it.

The full story of XR750’s reign also happens to be very much a modern one. Of those 18 non-Springsteen/Parker/Carr titles, the bulk of them came following Carr’s final Grand National Championship in 2005.

It’s only due to recency bias that it feels like the recent history of American Flat track can be summed up as the rise of the Kawasakis — culminating in Bryan Smith’s 2016 crown — followed one year later by both Harley-Davidson’s full pivot to the XR750’s successor — the production-based XG750R — and the return of Indian Motorcycle with its purpose-built XR killer, the FTR750.

The reality is the XR750 played as the backdrop for all of those monumental developments, leading ubiquity to instantly seem like antiquity.

The all-guns-blazing reemergence of Indian Motorcycle, in particular, had a massive impact on the sport. Indian followed the blueprint utilized so effectively by Honda in the mid-’80s with its once-dominant RS750 and perfected it with the added edge of three decades of technological advancements to call upon.

2000 Grand National Champion Joe Kopp was brought onboard in a testing and developmental role in 2016 and found the FTR to be instantly familiar following a long and successful career campaigning XRs.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

He said, “It has a purpose-built engine like in the XR750… I wouldn’t say they copied it, but there are a lot of the same things, like a four-speed transmission and big heavy flywheels on the crank… a lot of similarities.

“The only thing that’s really different, I’d say, is the modern technology with fuel injection and ignition timing and stuff like that.”

Kopp gave the all-new FTR750 its AFT debut in a shakedown ride at the ‘16 season finale ahead of its impending full-scale 2017 campaign.

The 47-year-old turned some heads with his seventh-place run in the Indian’s maiden performance at the Santa Rosa Mile, but that effort was largely overshadowed by Brad Baker, who gave the XR750 a proper sendoff by winning the machine’s final outing as a full-factory racebike in blowout fashion.

There was no denying Indian Motorcycle the spotlight the very next day, however, when it enacted the next stage of its plan for dirt track domination. Yamaha had beaten H-D and its superior XR750 in the ‘70s thanks primarily to the singular brilliance of Kenny Roberts. Honda had then done the same with its outstanding RS750 and a pair of superstars in Ricky Graham and Bubba Shobert in the ‘80s.

Indian took it one step further. It hired the series’ three most recent Grand National Champions, Smith, Baker, and — the biggest catch of all — Jared Mees, assembling its own version of the “Wrecking Crew.”

By that point, Mees had been well on his way to expanding the exclusive “Titans of the XR750” club to four. Before signing with Indian, he’d already claimed four GNCs on the XR and ranked seventh in the machine’s history with 20 victories to his credit.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

Since joining Indian, Mees has only accelerated his assault on the record books, storming past Springsteen in all-time wins (now with 48 to Springer’s 43, trailing only Parker’s 94 and Carr’s 78).

And as a result, the perception of his place has likely been forever altered; the same way Ricky Graham, who took the 1982 Grand National Championship on an XR750, is best remembered as the master of the RS750, Mees seems destined to be most closely aligned with the FTR750 after his racing days are done.

Mees clinched the FTR’s first title in its opening attempt with two races still remaining in the 2017 season. With the championship already locked up, he entered the penultimate race of the year in Fort Worth, Texas, riding a run of five consecutive oval wins (a streak that likely would have been eight if not for some uncharacteristic start line mishaps at Lima)

Similar to the situation that helped pave the way for Honda’s overwhelming success in the ‘80s, Indian’s ascent transpired while H-D’s factory race program was most vulnerable, deep in the development phase of the new XG platform.

Yet, despite being “officially” left behind, the XR750 still had some fight left in it yet.

Privateer Jeffrey Carver, Jr., showed up for the Lone Star Half-Mile in a van with just crew chief Ben Evans in tow and a single XR750 loaded up with them.

Photo: Scott Hunter, American Flat Track

“We actually broke our Kawi the week before,” Carver explained. “We thought we were going to have to ride the backup, but its motor wasn’t as good. We were sitting there at the shop, and Gary Goodwin was there. He had given us an XR, and he was like, ‘What about that bike?’

“’I don’t know… We’d need two of them.’

“‘Welp, you’ve got one good one and that’s all you need. Imagine being the last one to ever win a race on an XR750.’

“Man, I was so fired up. I’m not one to say, ‘Hey, we’re going to go to this race and win. I just let the energy play itself out.”

Even with a field stacked with Indian FTR750s, H-D XG750s, Kawasaki Ninja 650s, and Yamaha FZ-07s, nothing stood a chance against Carver and that XR750 on a slick Texas Motor Speedway surface.

Nine-time GNC Parker said, “When you’re on a track, the XR delivers the horsepower down to the track. When it gets slippery, the XR just has the characteristics to really hook up to the ground. The Yamahas struggled at that in their era and the Hondas struggled at that for a period of time too. That’s the big thing of it. It will hook up to the racetrack where the other bikes would struggle trying to get tires to hook up onto the dirt.”

Carver said, “I had been close — podiums and running up front. At the beginning of that year, I was going to quit and maybe try to find something else to do, at least part time. I didn’t even know if I was going to the West Coast for the races. To come out and have that drive and that grit… I didn’t care — you had the factory Harleys, the factory Indians. To be able to go there and win… It was just amazing. I just had this determination in my eyes that day.”

Only one rider could so much as keep Carver in sight that evening — Mees, who finished over a second-and-a-half back in second.

Photo: Scott Hunter, American Flat Track

“I tried so hard to gain on him… I couldn’t bridge the gap,” Mees admitted.

Photo: Scott Hunter, American Flat Track

As the weekends and seasons continue to add up, Carver’s underdog victory in Texas seems more and more likely to go down as the XR750’s last hurrah. He did wheel it back out at the Atlanta Short Track early in 2018 to score another podium finish, but the series has only further fallen into Indian’s clutches.

Since Carver’s upset, the FTR750 has taken 34 out of a possible 37 Main Event triumphs. Meanwhile, while improving, Harley’s factory XG750R racebike is still looking for its first.

Photo: Scott Hunter, American Flat Track

While impossible to predict at the time, Carver did give the XR750 one final bragging right. The FTR750 closed out the decade with 47 wins. And thanks to Carver, the XR750 ended the 2010s with 48.

The XR750 is now largely absent from AFT competition. Danny Eslick did manage to score points on it last season at Lima, but that served as only a fleeting reminder of the potential of its continued relevance.

Kopp said, “Sure, one hasn’t won since 2017. But we really haven’t seen them much on the track since then with a real capable rider. Honestly, there are some tracks… if I was 20 or 30 years younger, I would still choose the XR750 at times over an Indian, honestly.”

Asked if he believed it could still win, Parker said, “I do. I really do. Why would you not expect it? My career ended in 2000. Twenty years later… They kept tweaking it here, tweaking it there… You can have a 1000-horsepower motorcycle, but you’ve still got to hook it up to the ground, and that’s the key issue. Just because you’ve got a faster, more powerful bike, doesn’t mean you can go faster around a circle.”

Kopp added, “I know you could still win on that thing. There are certain tracks where it’s favorable in my mind. A slick clay car track — the slicker the better for that thing — and with a more rounded straightaway, it would be hard to beat still. I’m confident in that.”

Imagine that… For all the obvious reasons laid out in this series and multitudes left unstated, the XR750 is widely considered to be the most successful racebike in motorcycle racing history — perhaps the greatest vehicle in motorsports history. Is there even any competition? What other mechanical wonder boasts a half-century reign spent transforming talents into heroes and heroes into legends? And best of all, this legacy might not yet be fully written.