Honda CB750 History

With Ian Falloon

Until the late 1960s motorcycle with four cylinder engines were exotic and expensive. Emphasising smoothness, luxury and power, for most people a four was only a dream.

Gilera and MV Agusta fours dominated 500 cc Grand Prix racing through the 1950s, and were joined by Honda in the 1960s. But these were exotic racing machines, far removed from the affordable British parallel twins that dominated the large capacity motorcycle market.

As far as production motorcycles went, by 1969 the Ariel square four was a distant memory, and the Henderson fours of the early 20th century even more so. The only other fours available were the hugely expensive and unobtainable 600 cc MV Agusta and equally exotic Munch Mammut.

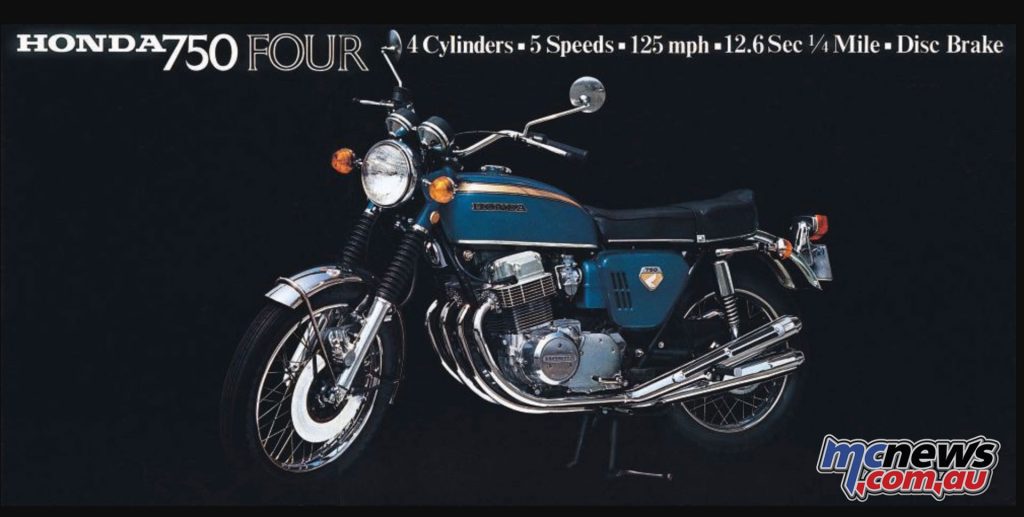

After Honda introduced the CB750 KO motorcycle engineering immediately leapt forward a generation. The CB750 provided refinement and civility that was previously unheard of and it immediately became the standard against which all others were judged. Mass-produced in quantity it also provided technological superiority at an affordable price.

Traditionalists were worried that it was too complex and would be unreliable but these views were ill founded. Honda had been successfully racing highly stressed multi-cylinder bikes for many years and their street machines had already earned a reputation for reliability. Until the CB750 the vertical twin ruled motorcycling, but this changed overnight.

The beginnings of the CB750 went back to early 1968. Honda was about to withdraw from Grand Prix racing, and with their flagship CB450 struggling in the marketplace Soichiro Honda had an idea to produce a “King of Motorcycles”. Speculation at the time expected the new engine to be based on the existing twin-cylinder N360 car, but in February 1968 Bob Hansen from American Honda changed this.

Hansen (Team manager of the CR450s at Daytona in 1967) mentioned to Soichiro Honda that they should develop a four-cylinder machine. Over the next six months head of R&D, Yoshiro Harada, and stylist Einosuke Miyachi produced a prototype CB750. The first public showing was at the Tokyo Show in October 1968, and by June 1969 the first examples were available in the US.

The earliest production models included a number of differences to later examples, but there were some initial problems. Many of these were quite serious, and in the first year Honda released 100 pages of technical and bulletin updates. The newly formed Four Owners Club in America even wrote to Congress and the Governor of California (then Ronald Reagan) complaining of the problems.

Until number 1007414 the engine cases were roughly finished die-cast, which looked sandcast. This was because Honda didn’t anticipate demand to be so strong and were not geared for full-scale mass production. A large number of these early “sandcast” CB750s were produced (53,399), and despite their problems have become the most sought after of the genre.

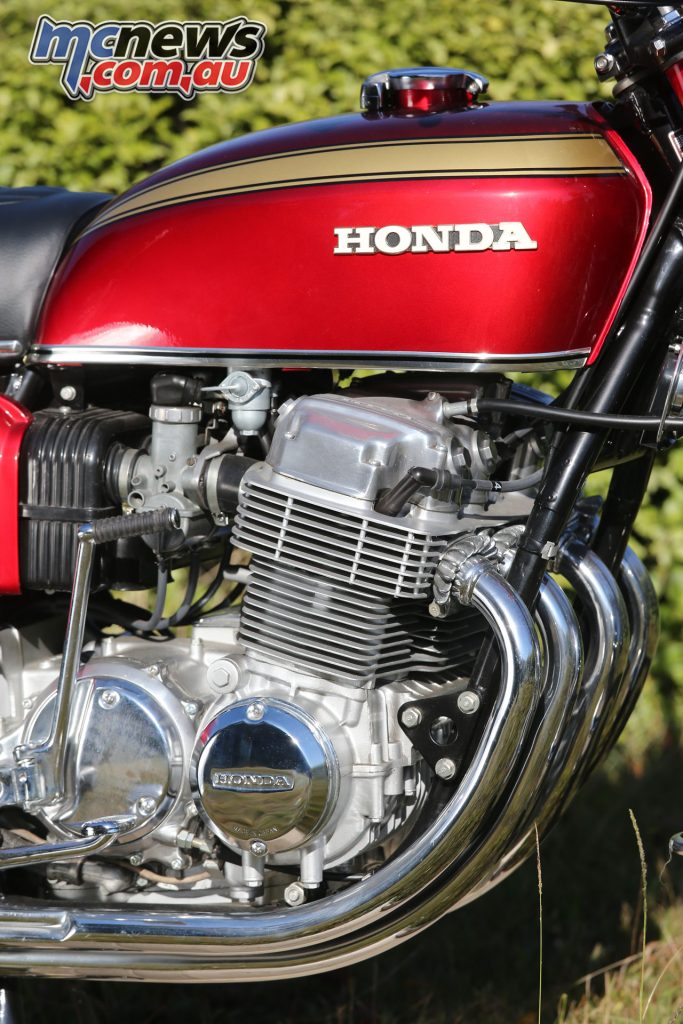

The CB750 four-cylinder engine incorporated many departures from usual Honda practise. Undersquare dimensions (61 x 63 mm) were chosen to minimise engine width, and the crankshaft was a forged on-piece type with five plain main bearings and relatively small (36 mm) journals.

The primary drive was by dual endless chains driven from the centre of the crank to a multiplate clutch and indirect five-speed gearbox. A single row chain drove the single overhead camshaft while the one-piece cylinder head featured two-valves per cylinder (32 mm intake and 28 mm exhaust), set at a relatively shallow included valve angle of 60 degrees.

The four cast-alloy pistons provided a compression ratio of 9:1, and carburetion was by four 28 mm round-slide Keihin carburettors. A departure from Honda’s norm was dry sump lubrication with a frame-mounted oil tank. Ignition was by points and coil, with two sets of points positioned on the right end of the crankshaft, while an automotive-style three-phase 210-watt alternator sat on the other end.

The 12-volt electrical system included an electric start motor, ensuring a new generation of riders was able to experience 750 cc motorcycling. No longer was there a natural selection of riders due to their ability to kick-start the motorcycle, and the electrical system was so reliable that the CB750 could be ridden across the country without fear of failure.

The power output of the 736 cc four was a moderate 67 horsepower at 8,000 rpm, but this was still considerably more than the 58 horsepower of the rival BSA and Triumph triples. It was also enough to provide a top speed in the region of 200 km/h, making it one of the fastest bikes on the market. Compared to the British competition it also ran more smoothly, stopped much better, and could accelerate through a standing 400 metres in 13 seconds time after time without destroying itself.

The heavy (78 kg) four-cylinder motor was the CB750’s focal point, but as was usual of Japanese motorcycles of this period the chassis wasn’t as impressive. The 218 kg dry weight and reasonable power taxed the double cradle mild steel frame and Showa suspension to the limit.

The front fork featured alloy legs, and rubber gaiters, but the 35mm fork tubes were weak, and the steering head bearings were still a ball bearing type. The swingarm was a two-piece welded stamping rather than the usual tubular steel, and the rear shock absorbers may have been a de Carbon type, but the only adjustment was a three-way spring pre-load.

Fully chrome-plated with upper spring covers they looked a lot better than they functioned. The 19-inch front and 18-inch rear wire spoked wheels were normal for large capacity motorcycles of the period, but the Japanese-made 3.25 x 19 and 4.00 x 18-inch Dunlop or Bridgestone tyres were particularly hard and slippery.

The most interesting chassis component was undoubtedly the front brake, claimed to be the world’s first hydraulic disc brake on a production motorcycle. In the interest of maintaining a clean look, Honda fitted a 300mm stainless steel front disc instead of the superior, but rusting cast-iron type.

They also installed a finned Tokico single floating piston caliper, this also inferior to the twin opposed piston type favoured by racers. The underlying impression of the chassis specification was that function was secondary to form, and in this respect the CB750 still left something to be desired.

Where the CB750 really scored was in its looks and finish. From the distinctive four chrome-plated mufflers to the rather brutish 16-litre fuel tank, the CB750 was imposing, and one of the more attractive Japanese offerings of the period. It may have been heavy, long, high, and wide, but the CB750 was the perfect motorcycle for America where razor sharp handling was considered less important than reliability and load carrying capacity.

In September 1970 the considerably revised CB750 K1 replaced the CB750. Updates included a new seat, and black air cleaner box. Production increased to 77,000 before the CB750 K2 replaced it in March 1972. It took a seasoned expert to tell the difference between the CB750K1 and K2, but visually there were chrome-plated headlight brackets and a new instrument panel with four warning lights, borrowed from the CB500. A quieter exhaust system was undoubtedly responsible for a drop in performance, but Honda was on a roll, and production still totalled 63,500.

The 1973 CB750 K3 received a new fuel tank stripes, and a number of engine modifications to reduce oil consumption and noise. The performance was further diminished, but the suspension now included conventional five-way adjustable rear shock absorbers. Apart from colours the 1974 CB750 K4 was similar to the K3 but by now the Kawasaki 903 cc Z1 had usurped the CB750 as the supreme production roadster.

This still didn’t stop Honda selling 60,000 CB750 K4s to become the top selling motorcycle in the US in 1974. All along it received little updates, and while not the fastest Superbike, the myriad of refinements and attention to detail ensured its popularity. For 1975, the CB750 K5 was little changed, but was usurped by the GL1000 Gold Wing as Honda’s range leader.

While the CB750 didn’t introduce any engineering breakthroughs, it benefited from the innovative production techniques developed by Honda during the 1960s. The first CB750 was a strong, visceral and exciting motorcycle that gradually became sanitised over its lifespan. As the power was reduced, within a few years the CB750 was no longer the performance king.

By 1977, as the CB750K, it was only a shadow of its former self. But back in 1969 the CB750 was the most significant motorcycle to appear in thirty years and is possibly the most important production motorcycle of all time. So influential was the CB750 that the transverse-mounted in-line four-cylinder engine became ubiquitous and dominating.

This year, 2023, Honda will release a CB750 powered by an all-new parallel twin.

Honda CB750 K1 Specifications

| Honda CB750 K1 Specifications | |

| Engine | Air-cooled, four-stroke, tranverse four-cylinder, SOHC, two-valves per cylinder, 736 cc |

| Bore x Stroke | 61 x 63 mm |

| Compression Ratio | 9.0:1 |

| Induction | Four 28 mm Keihin carburetors |

| Power | 50 kW [67 hp] @ 8000 rpm |

| Torque | 60 Nm @ 7000 rpm |

| Clutch | Wet, multi-plate |

| Transmission | Five-speed, chain final drive |

| Frame | Steel tubular duplex cradle |

| Front Suspension | Telescopic forks |

| Rear Suspension | Dual shocks, preload adjustment |

| Brakes | 296 mm front rotor, single-piston caliper, 179 mm rear drum brake |

| Tyres | 3.25 x 19 (F), 4.00 x 18 (R) |

| Wheelbase | 1453 mm |

| Seat Height | 800 mm |

| Weight | 226 kg (wet) |