Orphans Pt6 – Phil Hall

It can’t have escaped your notice that the majority of “orphan” bikes that I have highlighted in my series have been products of the 80’s, that glorious era when the Japanese manufacturers thought that money grew on trees and that they had a moral obligation to produce a model to suit every class. If there wasn’t a class to suit, they would simply CREATE one and so the bewildering plethora of models that emanated from Japan was somehow expected and accepted .

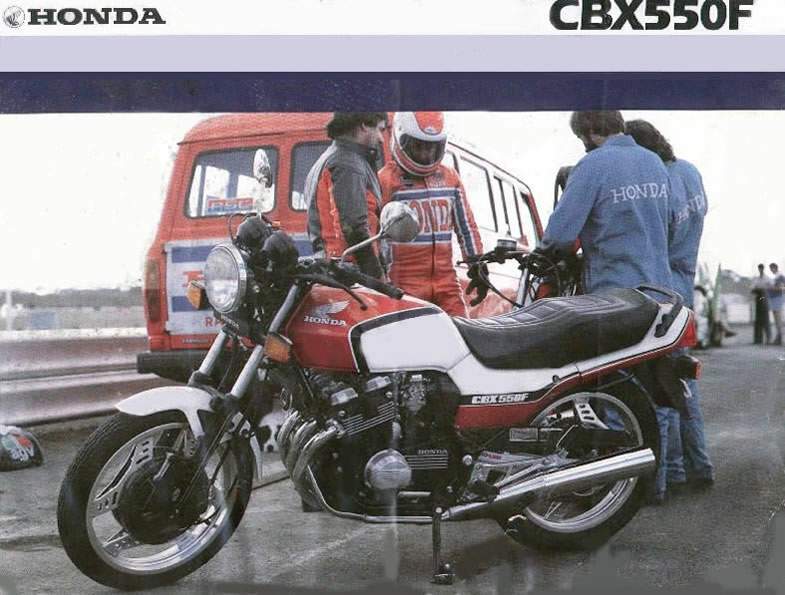

In the perverse way that my mind often works, I have left the orphan with which I have been most familiar till now, well into the telling of these sad bikes’ stories. This week I’d like to look at the 1982-86 model CBX550 from Honda. I feel I can speak with some authority on this bike having owned 3, yes, THREE, of them over the years.

As noted above, the Japanese manufacturers, determined that none of their competitors gain a market edge, watched each others’ output with a passion and, if one of them released a new model, you could be sure that the others would follow. And so it was that, in the middle of 1982, two new 550cc middleweight bikes appeared almost simultaneously.

The Honda was a completely new model while the Kawasaki GPZ550 was a refinement and upgrade of the existing Z500 middleweight. The Honda was nominally produced up till 1986 but its day was done long before that, and, from memory, its day as a catalogue model here in Australia was done by 1984. The Kawasaki lasted a year longer, the sporty GPZ finishing up in 1985.

Both featured DOHC 4 cylinder engines, the GPZ being 553cc and the Honda having a capacity of 572cc. Both were styled to demonstrate a lineage to their larger stablemates, the GPZ mimicking the styling of the 750 and 1000cc variants and the Honda that of the 750/900 Bol d’Or models and the CBX1000 six cylinder. Both Incorporated mechanical and ancillary features from the bigger models and both attempted (at least one of them successfully) to capture the lucrative middleweight sportsbike market.

The sale of my house in Canberra in 1982 presented our family with an opportunity to upgrade the fleet, as it were, so we bought a much newer car and I sold my 1973 500/4 with a view to buying a newer bike. I wanted a similar capacity bike as the 500/4 and the choice came down to the Honda and the Kawasaki. After much research (on paper – no internet), I chose the Honda over the Kawasaki, even though all the road tests said that the Kaw was a better bike (it was, too). I had been a Honda man pretty much all my riding career by that stage and I reasoned that, even though the Kawasaki WAS a better bike, its styling was a little conservative and, compared to the swoopy Honda with its myriad of “trick” features, it was an easy choice.

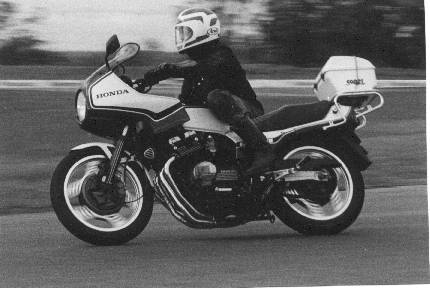

Features? The bike bristled with them. The instrument panel was pure CBX, as were most of the controls. The rear suspension was Honda’s new Pro-link rising rate jigger with an airbag spring rather than a metal one. The front forks were also air assisted with the forks being linked by a balancing tube attached to the fork caps. The front suspension also featured Honda’s version of the anti-dive braking mechanism fitted to their bigger bikes. The wheels were Honda’s latest version of the Comstar range introduced back in the late 1970s and all of these styling features were set off by a tricolour colour scheme that pointed to Honda’s racing heritage and a swoopy 4-into-2 exhaust system that was art in itself. It paid tribute to the “bunch of bananas” exhaust of the legendary 400/4 and this feature, more than any other, indicated that the bike was clearly intended to the spiritual successor of the 400, one of Honda’s best-selling and most-loved models. The fact that the exhaust system came with incipient rust was not pointed out to potential buyers, however. My 1982 model that I bought from Lenny Willing’s shop at Wyong, had 21000k on the clock and the exhaust mufflers were already rusted through. It was almost unheard of to see a CBX still with the standard mufflers. Some owners kept the existing headers and fitted after-market mufflers and so retained the swoopy look. Others, like me, ditched the whole setup in favour of a 4-int-1 (mine from O’Briens Exhausts at Kirawee).

Then there were the brakes. Disks all round, two on the front and one on the back. But they were unlike any that had been seen before and it was the quirkiness of the brake set up more than anything else that probably contributed to the bike’s early demise. Instead of the brake disks (ventilated) being attached to the hub in the centre, as is conventional, they were attached at three locations to the OUTSIDE perimeter of the hub with the callipers gripping the disks from the inside of the disk not the outside. The whole setup was then encased in a metal shroud that was designed to keep water and debris off the disks and allow the use of steel rather than alloy disks as was the Japanese fashion of the day. At a quick glance the whole setup looked a little like the twin leading shoe brakes that were common before disks came onto the scene.

Yes, they worked brilliantly in the wet (most Japanese disk brake setups didn’t) exactly as the makers intended. So, why didn’t they last and why are they now seen as the bike’s Achilles Heel? For a start they greatly increased the unsprung weight of the front end and so contributed to an annoying front end wobble that was very hard to eliminate. I tried just about everything I knew but was never able to do so. Secondly, they were clunky and hard to service, adding considerably to servicing costs. Mostly, though, they were just unnecessary. In the intervening time between design and release, the long-running problems with Japanese disk brakes had been largely solved. Even Honda itself admitted this was so when they released the “sports” version of the VT250 with a set of double “normal” disks in place of the enclosed disk the first model had sported.

The real problem with the bike, however, was a poorly designed timing chain tensioner. It started rattling from about 20k from new and no amount of modification and fiddling was able to solve that one either.

What were they like to ride? Very enjoyable once a few modifications had been made. The air-assisted front forks were useless. I had some aluminium spacers made that sat on top of the springs and that improved the front end considerably. There wasn’t a lot you could do with the rear end, however. The ProLink rear spring/shock unit sat vertically behind the gearbox and, as soon as a few k’s were up, the heat from the gearbox would overheat the oil in the shock and the bike would start to wallow uncomfortably, especially in long corners. Performance was excellent, the DOHC 16 valve engine had plenty of “zip” and, as long as you didn’t slow down or stop at intersections, the wind noise would carry away the rattling sound from the timing chain tensioner. During the long tenure when I rode my bikes, I lost count of the number of people who would pull up beside me and point quizzically to the engine? My normal response was simply to shrug my shoulders!

I owned three examples, all with the red/black/white colour scheme. The first was a genuine F2 model with the F2B 900 replica fairing. The second was just an “F” with no fairing and the last was an “F” which the previous owner had carefully upgraded to F2 specs by purchasing all the necessary bits from Parry’s Motorcycles at Pennant Hills and doing the job himself.

I loved my time with my CBXs. I even created my own web site about them www.halltech.com.au/CBX and I still receive emails from people all around the world asking me all sorts of questions about the model. Most recently a gentleman in Sweden contacted me telling me that he had acquired a reasonable example and did I have any tips for him? Peter has now completed the restoration and is happily riding his when the weather allows.

Mostly we lose track of our bikes when we sell them but I know exactly where my last 550 is and its owner keeps me regularly informed about its comings and goings. How I met her and how she came to buy it is a fascinating story in itself which I must one day tell. However, despite my viewing the bike through red, white and blue glasses, the fact is that it was another of Honda’s orphans which, apart from the memories of a few fanatics, sank without a trace.