1979 Honda NR500

Four-stroke tech in a two-stroke world

Honda went Grand Prix racing with a four-stroke machine in a two-stroke era

When Honda originally announced rejoining Grand Prix racing in 1977 they did so with the aim of competing with a four-stroke machine, mirroring those motorcycles they sold.

They had originally withdrawn from GP racing following 1968 when a 500cc, four-cylinder limit was added, with the NR500 to be a highly technological offering if it were to compete with the competitions two-stroke machines.

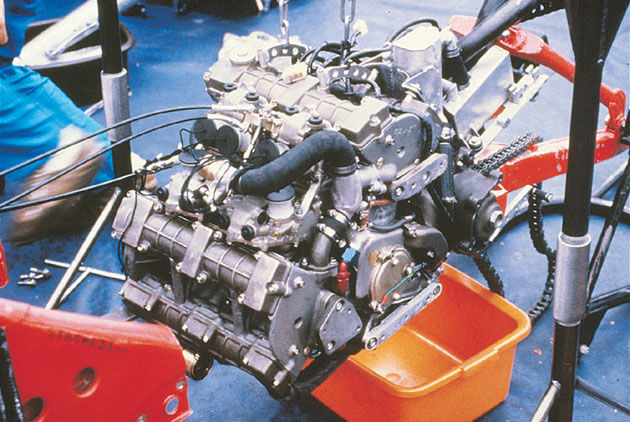

Honda returned to the 500 cc class of the World Motorcycle Grand Prix series in 1979, following a twelve-year hiatus. The machine they had developed for their comeback – an entry in the World Grand Prix’s most prominent class – was the NR500, powered by a four-stroke, DOHC V-four engine. With its oval piston engine incorporating eight valves and two connecting rods per cylinder, plus an aluminum semi-monococque frame complete with an inverted front fork, the machine surprised everyone with its daringly innovative technologies.

“When I look back at it, I’m not sure if we were experimenting with cutting-edge technologies or obsessed with foolish ideas,” recalled Toshimitsu Yoshimura, an engineer involved in the development of the NR500’s oval piston engine. “At least we were doing something that was beyond the realm of conventional thinking. I’m not just talking about us, who were designing the engine, but also those who were creating the body. The emphasis was to create a difference-not just any difference but the difference that would work to our definite advantage. That’s why we decided that Honda should go with four-stroke engines. We wanted to achieve our target through innovative technology, and in so doing have the edge over our competition.”

Adding to the Honda preoccupation with four-stroke engines was the fact that many in top management, who had decided to make a comeback in the World Grand Prix series, and those involved in the development, were imbued with the philosophies of Soichiro Honda, who had criticized two-stroke engines as being little more than “bamboo tubes.” To them, it was simply out of the question to reclaim their victory with anything less than a four-cycle engine.

Yoshimura, who had actually designed the engine, was from the very beginning a staunch advocate of the four-cycle approach.

“Four-stroke engines,” he said, “have distinctive mechanical processes. The (intake) valve closes tight, combustion occurs, the exhaust valve opens, and the exhaust is released. It’s a sequence of independent processes, each with a different function, working together to facilitate the engine’s entire operation. This is really fascinating, from an engineering standpoint. I believe this mechanism will be the basis of further advancement in engine technology.”

Honda announced its plan to go back to the World GP circuit the following April, 1978. Accordingly, a new organization called the NR (New Racing) Block was formed at the Asaka R&D Center for the purpose of developing racing powerplants. When the project began, the engine development team had only three very young staff members. But Honda had established key objectives for the resumption of racing operations. Assembling a young development team was very much in keeping with one such objective, which was to “foster young talent with the spirit of racing.”

Yoshimura, who was only in his sixth year at Honda, didn’t have any experience with Honda’s past racing activities. Ideas such as “resuming racing activity” and “returning to the World GP circuit” had simply not crossed his mind.

“Instead of being excited about developing racing machines, our feeling was more akin to raw determination”, he said, “It was the determination to create something that would represent the very best in technology. We were determined to create an engine to surprise the whole world. We believed that if we could create the best engine, it would bring us a victory.”

The average output of Honda’s rival two-stoke engines was in those days around 120 horsepower. Although horsepower isn’t the only determining factor in a victory, the development staff knew they should first achieve a degree of power output exceeding that of the competition.

World GP racing regulations limit the number of cylinders to four. Accordingly, for a four-stroke engine to be as powerful as a two-stroke unit, it has to achieve twice its normal rpm. To achieve that, the team had to enhance the intake efficiency and design a valve system with higher resistance to friction and heat buildup at high revolutions. Given these conditions, the idea was born to double the number of valves to eight. As they examined the potential valve positions in the context of their four-stroke engine layout, the team came up with an idea of changing the piston’s shape from a circle to an oval.

“The reason was simply that we were all so young,” Yoshimura said. “We had nothing to fear. You could even say we had no preconceived notion that a piston had to have a circular cross-section. We were determined that the oval design was the key to outperforming two-stroke engines.”

According to their calculations, the eight-valve oval-piston engine would offer an estimated output of 23,000 rpm and 130 horsepower. With such promising figures, the team set out on its quest for new technologies. They believed they had a winning idea, and now they needed the winning formula.

The idea of an oval-piston engine was not without a few doubts, of course. Could it achieve the calculated intake efficiency under actual running conditions? What about friction and the sealing of pistons? Could the engine be cooled effectively so that the pistons would not be deformed by high temperatures? Several problems needed to be solved, but no one was more aware of that than the development staff. In their desire to bring something new to the racing world, the voices of concern simply did not resonate with them.

“We didn’t think much about whether the engine would actually turn over,” Yoshimura recalled, “or even whether it would be practical at all. We weren’t worried about those things, since we just wanted to make it work.”

Testing with a two-valve, single-cylinder engine indeed confirmed that the oval piston would rev. They gradually increased the number of valves, in time reaching the eight-valve, single-cylinder. However, by this time the development staff had already gone through numerous problems.

The phenomenon of sudden disintegration was a significant obstacle, typically arising when the engine speed exceeded 10,000 rpm. The cause for this was the twisting of connecting rods. Unlike a regular piston, an oval piston has two rods. The rods would distort as the engine speed increased, pulling the piston pin out of its proper orientation and causing the parts to break. To solve the problem, not only would the design specifications have to be modified, but the machining accuracy would have to be improved. Accordingly, the development team worked with the staff at Honda Engineering (EG) to try various approaches.

The piston ring, also, was a real headache, since the oval shape was so difficult to machine accurately. Experiments were repeated over and over, through a process of trial and error. For example, they tested a split-type ring made of two parts and formed the ring into a “walking stick” shape. But after every conceivable alternative had been tried, they found themselves back at the starting point with a conventional, self-stretching piston ring. Even with that configuration they still had to expend extra effort calculating the appropriate dimensions, so that the ring would remain in free form during machining, but produce constant bearing pressure once installed. NC machines were still inaccurate during that period. Therefore, additional effort was required to produce the desired quality of a part by accurately reflecting the specified machining dimensions.

However, through persistent effort the team identified solutions to these problems, one by one. The completion of the piston ring, in particular, was a considerable boost to the feasibility of the overall design. With that, the test target moved from the single-cylinder design to four cylinders.

Another unusual feature on the early model was 16in wheels, when everyone else was running 18in.

ix months after the start of engine development, most of the problems already had been solved through the testing of single-cylinder prototypes. The next stage was to refine the basic design by applying the layout to a real-world racing machine. The development staff set up camp at Nasu Heights to work on the design, finally completing its layout for the four-cylinder, V-four stroke engine “0X” with a 100-degree V-bank angle. Bench testing of the 0X engine began in April 1979.

The 1979 season – the first year of Honda’s comeback effort – was now underway. But the 0X engine was giving the team all sorts of difficulties, from a damaged gear train to broken valves. Still, the engine was producing around 110 horsepower, so the staff had begun to think they should install it in a racing machine, where its real-world potential could be assessed.

“We wanted to identify the weaknesses in our new engine by seeing how it performed in an actual race,” remembered Yoshimura. “But since that was the purpose, no one was expecting it to do very well.”

The 11th Grand Prix race in the U.K was to be the powerplant’s first event. The speed of development would therefore have to increase in order that Honda’s machines could be ready for the race. Al though the initial target had yet to be achieved, the engine was already producing 100 horsepower at 16,000 rpm. Finally, in July a brace of NR500 machines was completed, each equipped with an 0X engine. The bikes, which were decidedly not in racing condition, set out upon the Silverstone circuit in August, there to display their prowess.

From the start, however, the debut was a particularly tough battle. In fact, the machines barely qualified for a place within the last group. Once the final race was underway, Mick Grant fell at the very first corner and retired. Takazumi Katayama also retired after several laps because of engine trouble. With both riders out of competition, Honda’s race had ended in disappointment.

Although the staff had not anticipated excellent results, they nevertheless wanted to see a powerful performance. Their shock was understandable as they observed the ever-widening gap between their machines and those of their rivals. The humiliation they also felt, was much worse than they could have expected. In the French Grand Prix, the final race of the season, their embarrassment was even greater, as both riders failed to qualify. Watching the riders leave the race, a devastated Yoshimura couldn’t fight back the tears.

“I felt miserable, just miserable,” he said. “Tears welled up in my eyes. Except for ours, all the bikes were using two-stroke engines. To be honest, I’d been hoping they would go to the final race and give us a really good run, even if it meant trailing at the very end. After the race they asked me to watch the video, but I couldn’t bring myself to see it.”

The engine was still unable to produce the amount of horsepower calculated in their specifications, and technically the machines weren’t in full preparation for the race. All excuses aside, however, the fact was that they had lost. The losses in the U.K. and France were a painful reminder that the road ahead was still very long.

Freddie Spencer rode the NR500 in 1981, however reliability remained a problem. In 1982 he would instead ride the NS500 three-cylinder two-stroke to third place, and took the World Championship title on a NS500 in 1983.

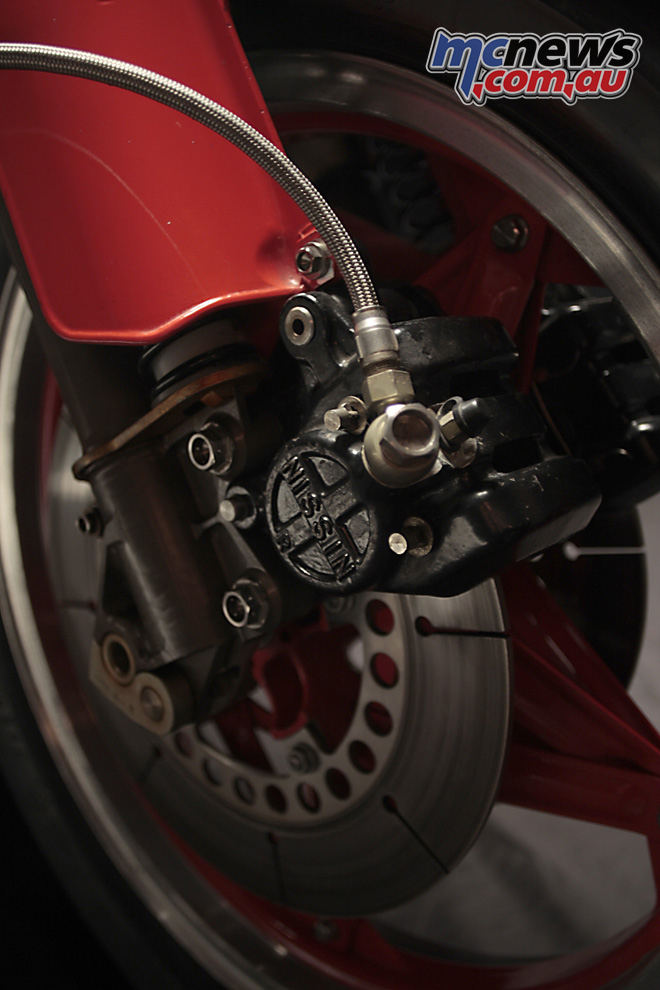

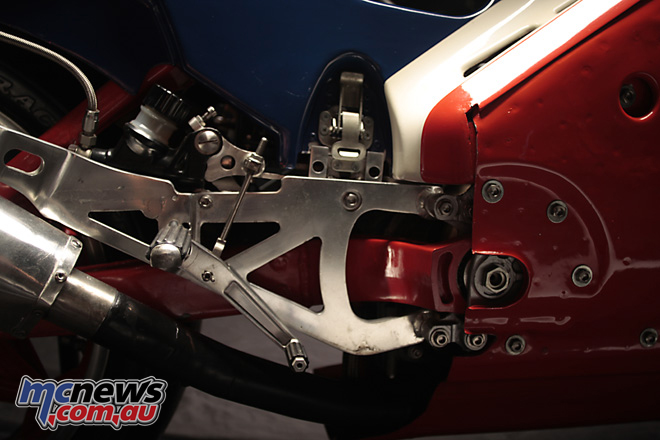

The NR500 was in a way, ahead of its time, with features such as the monocoque frame, magnesium components, swingarm and drive sprocket along the same axis, and back-torque limiters.

Key problems in the team’s engine design included the gear train and valve system. In the former, a reduction gear was initially used to turn the cam at half the rate of crank revolution. However, since it had been a source of frequent failures, a normal cam-reduction gear train system was adopted. Still, the problem refused to disappear. Numerous options were tried, after which the team came up with the idea of a rubber damper that would mesh with the cam gear. Fortunately, the design was a success, allowing the valve system to turn properly. Moreover, it resulted in higher power output.

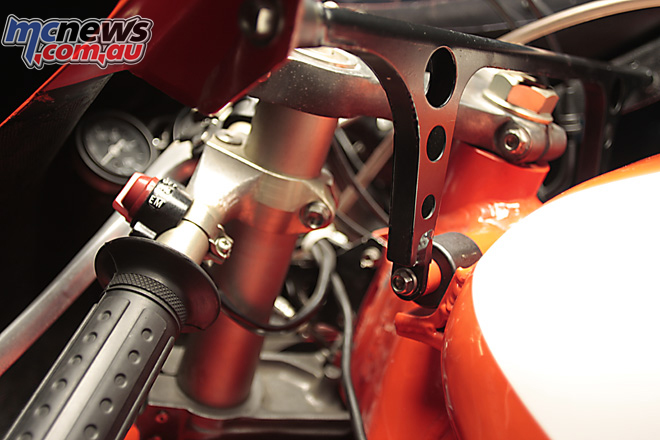

Additional areas of concern were the over-effectiveness of engine braking and a sudden burst of power when the throttle was opened (the so-called “bang”). The problem of engine braking was quickly resolved through the use of a device called a “back-torque limiter.” However, the team couldn’t find an absolute solution for the “bang.”

The NR500 improved slowly but steadily, thanks to the team’s dedicated effort. In 1982, their 2X modified engine achieved 135 horsepower, and in 1983, a 3X unit demonstrated output of 130 horsepower. The oval piston engines were at last on par with their rivals, at least in terms of output.

Despite their enhanced output, the performance of Honda’s engines was not so impressive on the track. Even though the Honda team earned a victory in the 1981 Suzuka 500-Kilometre Race using an oval piston engine, that was to remain their only triumph. The World Grand Prix series was an ongoing struggle.

Weight was a major handicap. Since the four-stroke engine required a larger cylinder head, its weight was greater by around 20 kg. The added mass surrounding the head also affected the machine’s center of gravity and overall balance. Measures were taken in order to reduce weight, including the replacement of iron with titanium and aluminum – already a light material – with magnesium. However, the precious improvement gained was quickly lost, as Honda’s rivals began using the same approach.

Other measures were taken to save weight. These included a reduction in the thickness of the outer crankshaft, which was subject to a relatively minor dynamic load. Often, before a race, the staff would labor overnight, grinding the parts with a pencil grinder. Still they were unable to overcome the weight disadvantage. It was a problem that would not be completely solved until a successor to the NR500 could be built.

Three years had passed since Honda’s highly anticipated return to the World Grand Prix series, but the NR500s had yet to win a race on the international circuit. Still, no losing streak could last forever, and Honda knew it. There was increasing pressure, both in Japan and elsewhere, for Honda to take the checkered flag.

As a compromise in the effort to get on the winners” podium, in 1982 GP series Honda introduced NS500 machines powered by two-stroke engines. The NS machines gradually replaced the NRs and, with that, came to play a dominant role on the world stage of motorcycle racing.

It also speaks to the performance of the two-stroke machinery of the age that a four-stroke simply couldn’t compete, despite the NR500 revving to almost 20,000rpm, offering 115hp and weighing 130kg. The monocoque frame on this model is aluminium.

The 3X engine was developed in 1983 as the last of the (oval piston) competition series. The 3X certainly had sufficient potential to win the World GP race, with an impressive 130-hp/19,500-rpm output. However, the remarkable results of the NS500 machines kept the 3X machines on the sidelines, shelved away in the pits. Finally, Honda decided to take the 3X off its roster of race machines without ever giving the engine a chance of competing.

“Although it couldn’t win a race,” said Yoshimura, “the 3X was very close to the complete form of an oval-piston engine, achieving more than 95-percent maturity.”

The development staff could, after all, achieve the engineering target it had set at the beginning. The experience, however, had left them with a deep sense of frustration.

“The engine was designed for racing,” Yoshimura said, “so we wanted it to be a winning design. If we had won at Laguna Seca, we could have been content with that and put a more peaceful end to the engine’s racing history.”

In reference to that, the engine did indeed have a chance of winning at Laguna Seca in July 1981. It was not a World Grand Prix race, but it was nevertheless an important event. During the race Freddy Spencer, riding his 2X, led Yamaha’s Kenny Roberts for quite some time. Although Spencer ultimately retired with an electrical problem, it was a race that amply demonstrated the 2X engine’s potential. Spencer’s brief but powerful domination had assured the development staff of the NR500’s potential, and despite all the hardships it was a lasting reminder of their effort and its ultimate value.

The NR500 concept was succeeded by the NR750, a commercial bike released in 1992. In fact, the back-torque limiter and other technologies evolving from the NR500 development saw their way into many mass-production Honda machines. The most precious outcome of the experience, though, was the spirit of challenge that was kindled by the original development staff and passed on to a new generation.

Reminders of the many trials involved in NR500 development have found a place in the hearts and memories of everyone involved. Until recently, in fact, a drawer in Yoshimura’s desk contained damaged connecting rods and broken valves, which came from assemblies that fell apart during early bench tests.

“Every time I saw those parts,” Yoshimura recalled, “they reminded me of the enthusiasm we had during development. They reminded me of a hotel in Nasu in the dead of winter, where we wrapped ourselves in blankets as we drew layouts because the heater wasn’t working. I remember our excitement at finally having completed the drawings. Of course, they also brought back bitter memories from those races.”

From its comeback in World Grand Prix with four-stroke engines to the creation of oval piston engines, Honda continued setting high goals and fostering the spirit of challenge in every aspect of development. The wealth of new technologies now possessed by the company is in no small part a result of these efforts.

“To create anything, you must put your heart and soul to it,” said Yoshimura, in nostalgic reflection on those days. “The development of oval piston engines impressed that upon me, as well as on the other young engineers.”

The parts are now gone from Yoshimura’s desk drawer. They were given to young development staff for use as reference materials in future endeavors. Yet, those parts are pieces of a dream that Yoshimura hopes will grow in the hearts of his successors and again drive them to new innovations.