Phil Hall talks Kawasaki’s racing successes from the 1970s to present day

You’d have to have been hiding under a rock not to have noticed the resurgence in the fortunes of Kawasaki over the last few years.

The smallest of the “Big Four” manufacturers has always steered its own path and has rarely strayed from the tried and true formula of picking the battles that it knows it is best equipped to win.

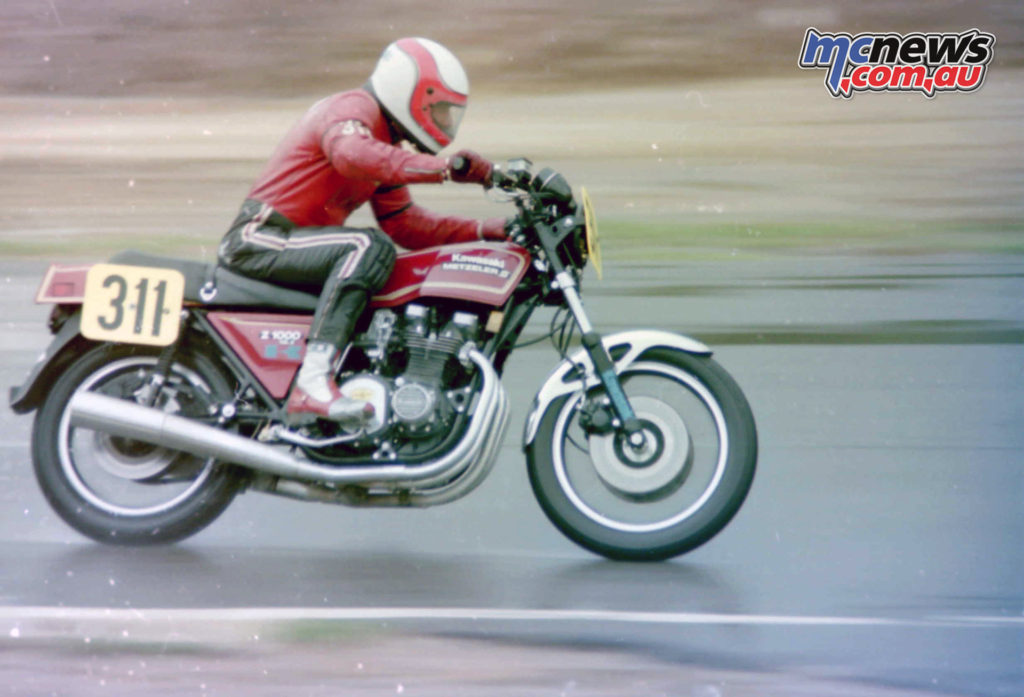

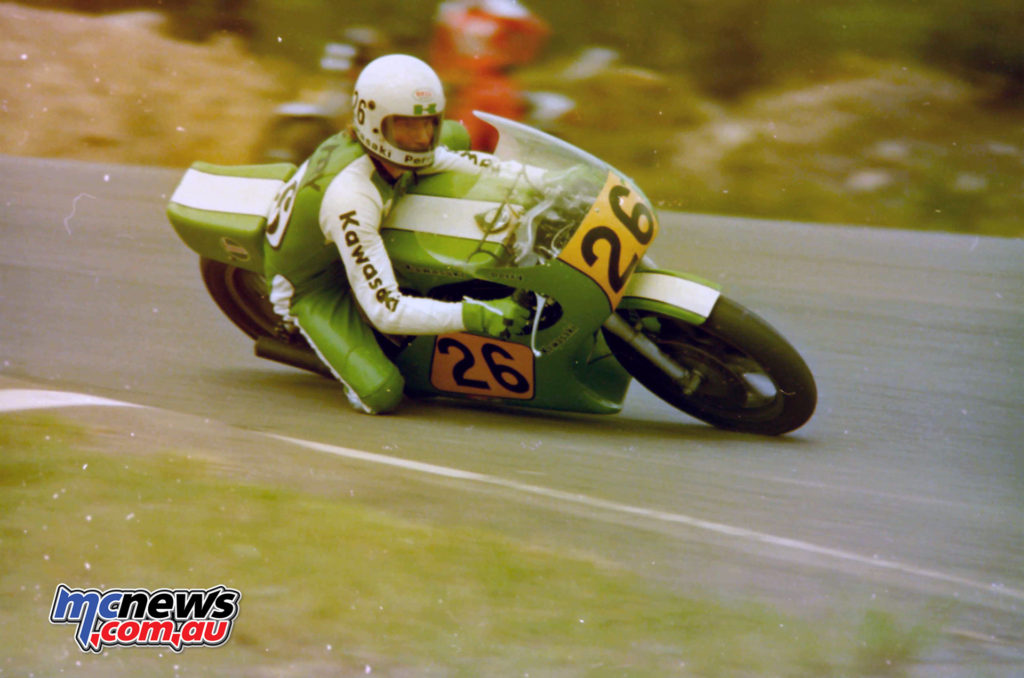

When I first got involved in road racing in the mid-1970’s, Kawaskai’s road racing division was flying high.

Using local distributors to manage the road racing efforts meant that the factory could be less hands-on and that their local agents got the spin-off in terms of kudos and on-going sales.

So there was a Kawasaki GB team, a semi-works team in the USA, a domestic racing effort and, of course, Team Kawasaki Australia. The factory did have its own team but it was very small and specifically directed towards the World Championships.

It was here that much of the in-house development took place while the “satellite” teams were also encouraged to do their own R&D as well.

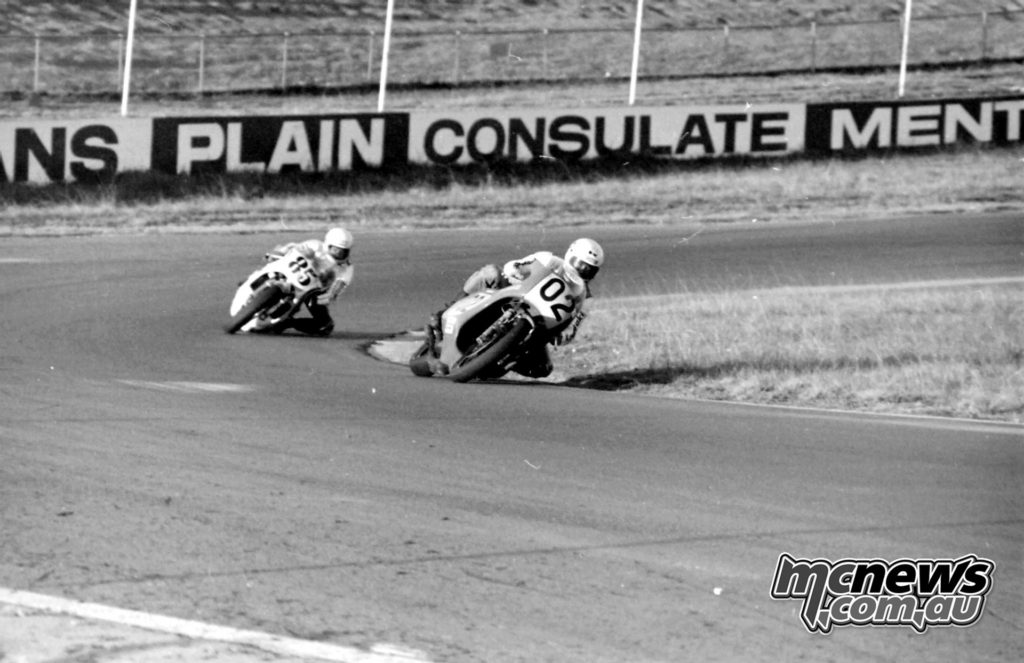

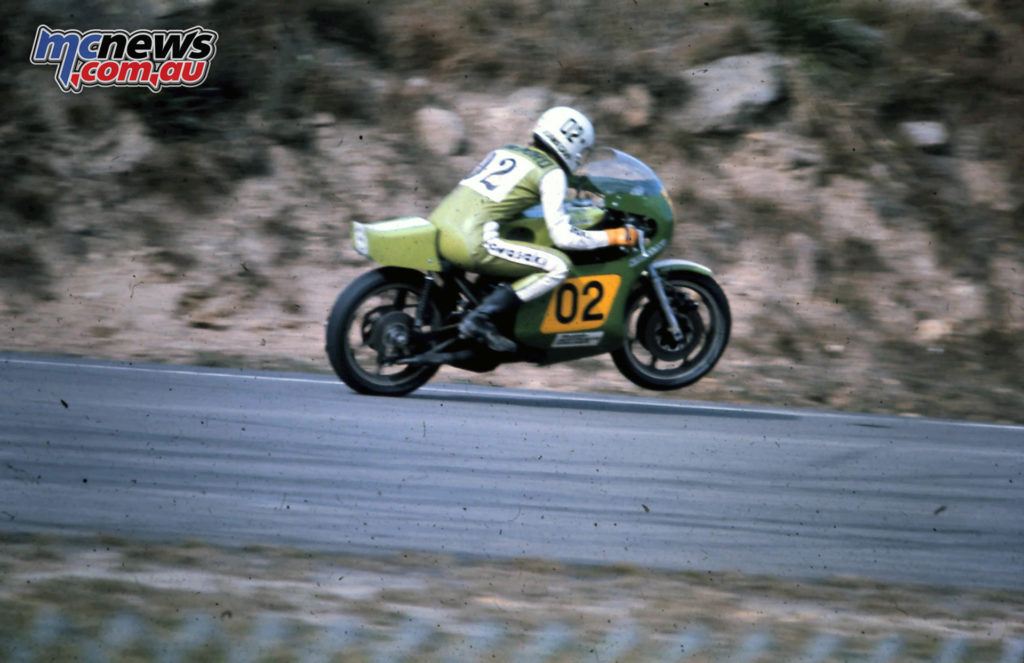

Of all of the satellite teams, TKA was the best managed and achieved the greatest success. The inscrutable Neville Doyle ran a tight ship and, after dominating with his two-bike team here, first with Toombs and Hansford and then with Hansford and Sayle, he moved the effort off-shore and added a world championship effort to the CV.

Toombs, Hansford and Sayle had already competed in selected overseas events, especially Daytona and some European shows and had achieved great success.

The overseas Kawasaki teams were stunned that a little-known effort from “down under” could actually have bikes that were more powerful, handled better and were more reliable than theirs which were usually far better funded.

As well they sat up and took notice of just how good the Australian riders were and they were encouraged to lift their game in the face of the newcomers.

In 1977 and 1978 TKA committed Gregg to a full-time tilt at the 250cc and 350cc world titles. Riding the iconic longitudinal twin in both classes, Gregg proved to be more than the equal of the “works” rider, South Africa’s Kork Ballington, and the little TKA effort went close to lifting a couple of titles.

I always maintained at the time (in spite of others decrying my opinion) that it was predominantly as a result of Gregg’s larger size and weight that Ballington was able to sheet home an advantage against a rider who was probably a better rider.

At the Australian Historic Titles at Lakeside in 2014 I brought this subject up with the man himself and, guess what, he confirmed my theory.

Ballington was short and much lighter in weight than Gregg and was always able to “tuck in” to the bike easier than Gregg and Kork said that, but for the physical disadvantage that Gregg had over him, he believed that he would have won at least a couple of titles.

Of course it is all academic now, but with Gregg also racing selected races in the F750 series as well and having to start riding much harder as Yamaha’s TZ750 became more refined, faster and more reliable, accidents started to happen more often and it was not really surprising that Gregg’s career was effectively ended after an accident in 1981 which damaged his leg.

But Kawasaki wasn’t done yet by any means. While the 750’s disappeared from the World Championship scene in 1979, the 250s and 350s went on (the less said about Kawasaki’s lamented 500cc contender the better).

In the hands of Anton Mang, they won four more titles in 1981 and 1982 before the inevitable tide of Yamaha domination swept them and everyone else up.

So Kawasaki showed that they could win at the highest level but that they were going to be very selective about it. The four-strokes moved in to racing and Kawasaki moved with it, winning with Wayne Rainey and Eddie Lawson (nine AMA Superbike titles isn’t bad), as well as many other riders all over the world.

Kawasaki refused to get involved in GP racing, many felt, because of the hideous cost. As the smallest factory (as noted before) they had the least to spend and the big-spending era of the ’90s 500cc two-strokes was not for them (even though the factory had considerable two-stroke expertise).

Kawasaki also put considerable effort into endurance racing at this time and experienced great success.

So it wasn’t really a surprise, when the MotoGP era was ushered in, that KHI decided it was time to come back. The new 990cc MotoGP bike was promising and, managed at a distance by Harold Ekl in the Netherlands, the team made slow, if unspectacular progress until the factory resumed complete control of the racing effort after a legal dispute with Eckl in 2007.

However, it was a false dawn and, despite some promising showings, mainly due to excellent riding by Australia’s Ant West, on January 9, 2009, Kawasaki announced it had decided to, “… suspend its MotoGP racing activities from 2009 season onward and reallocate management resources more efficiently.”

The company stated that it would continue racing activities using mass-produced motorcycles as well as supporting general race oriented consumers.

And so we come to today. It is now a matter of record that Kawasaki’s focus turned to the WSBK and it has been stunningly successful.

Of course the brand had already experienced success during the ’80s and ’90s in the hands of luminaries like Scott Russell who won the WSBK title in 1993 (against the run of play), Japan’s Akira Yanagawa and Australia’s Robbie Phillis, but the WSBK was the “Ducati Cup” for pretty much that whole time so there were slim pickings for the big K.

In 2009 Kawasaki resumed control of the WSBK effort after assisting satellite teams for several years before. The results improved considerably and Kawasaki riders started to become contenders.

In 2013 Tom Sykes won the WSBK World Championship and Kawasaki backed it up with double World Championship success with Johnny Rea winning in 2015 and 2016, his team mate finishing second both years. Kawasaki also lifted the Manufacturer’s Cup as well.

So, just at the moment, Kawasaki is the Special K. With a stable team, a history of success and a proven bike, it would be fair to say that they go into 2017 as favourites again.

Interestingly, it was Sykes who, in an interview with me several years back, said that he deplored the ‘dumbing down’ of WSBK saying that the new cost-saving measures brought in several years ago were really making superbikes no better than Superstock 1000 bikes.

Tom went on to say that he preferred the bikes to be raw and uncivilized rather than tractable and easier to ride!

Oh, and speaking of Special K, we’d better mention Kenan Sofuoglu. Winner of an unprecedented five world titles in Supersport (the last three on Kawasaki), “Superglue” is Kawasaki’s pin-up boy, the likable Turk looking set to make it six in 2017.

Sadly, the Supersport category is dying which is a shame and history may downplay his efforts in an atrophying class but nobody tries harder and nobody is tougher when it comes to a brawl than Sofuoglu.

And, just before I finish, here’s a few more special K’s. Brian Smith won the 2016 AMA Flat Track title on a Kawasaki, Robbie Bell won his second consecutive World Off-Road Championship title on a Kawasaki, Kawasaki won the Manufacturer’s Cup in the FIM World Endurance Championship, and the list goes on and on.

And that’s not even counting all the success that Kawasaki has had here in Australia. Kermit the Frog said that it’s not easy being green, but right now it couldn’t be a better time to be green!