KTM 790 Duke LC8c Engine

Engine design has moved a long way since the LC8 V-twin first debuted almost 15 years ago and KTM has put everything it has learned since those days into the engineering that resides inside the incredibly small crankcases of the new LC8c. The small c denotes ‘compact’ to identify it from its V-twin siblings. KTM has produced a parallel-twin masterpiece that pumps out 105hp at 9000rpm and 86Nm of torque at 8000rpm. That’s actually more power than what was claimed for the 25 per cent larger 990 when it was first released.

On the road the new smaller capacity donk does not match the last of their line 990 machines when it comes to punching off a turn. Don’t get me wrong, it bangs hard, but the power curve and delivery is so smooth (no doubt in large part due to the latest generation ride-by-wire systems rather than throttle cables), that it just digs in and drives with a minimum of fuss. It is infinitely smoother though than any KTM before it too, and will even go as low as 2500rpm in the upper gears without any grumbles. It turns over a mere 4000rpm at 110 km/h on the highway.

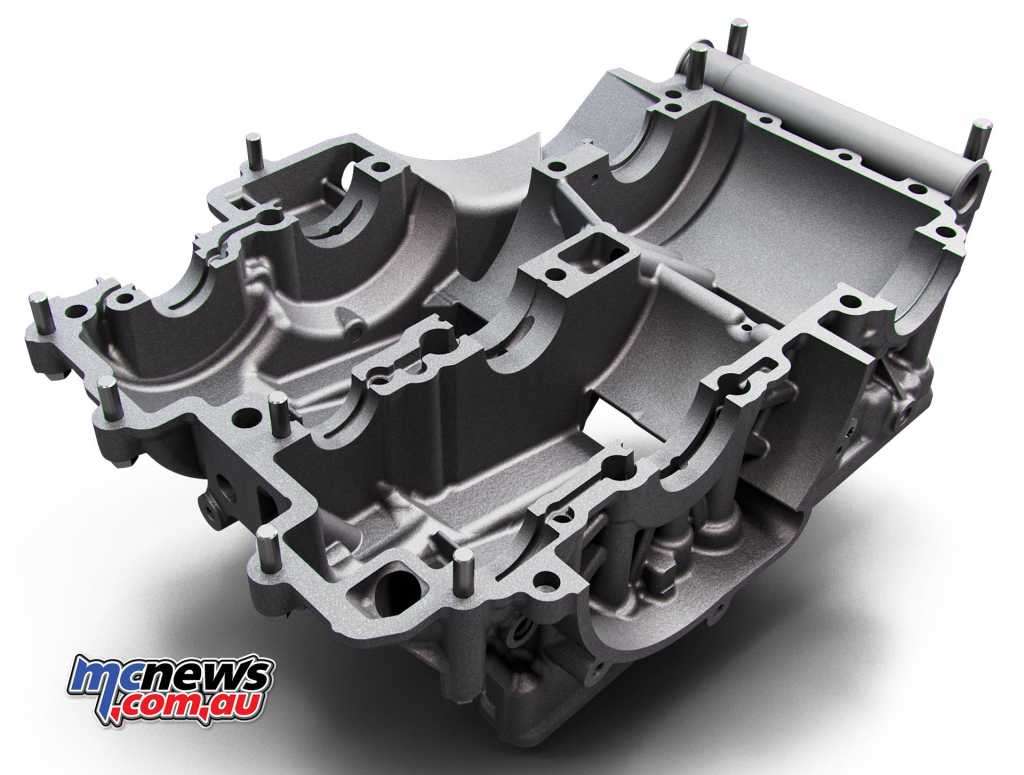

The new parallel-twin is a master-stroke of compact design achieved through exploring a lot of new engineering angles. All of which are aimed at making the new engine as physically small as possible. The result tips the scales at 50 kg, and whose actual dimensions are only fractionally larger than the 375cc single that power’s KTM’s 390 range of machines.

KTM has been quite brave in its search for ways to keep the engine size to a minimum. KTM designer, Kiska, essentially designed what it wanted from the bike in regards to dimensions and layout, then it was up to the engineers in Mattighofen to make it work.

New V-twin engines were tried but abandoned. There was no way KTM was going to be able to meet its goals in order to deliver what the pencil-pushers had drawn up for them to follow, so it had to be a parallel twin.

The new engine has completed hundreds of thousands of kilometres of dyno torture testing and burned through 36,000 litres of fuel in the process. Engineers fine-tuned the design with another 100,000 km of on-road testing completing the development cycle.

Making even a parallel twin to the dimensions required meant engineers had to think a little outside the square to achieve their aims, and the lengths they have gone to are quite surprising indeed.

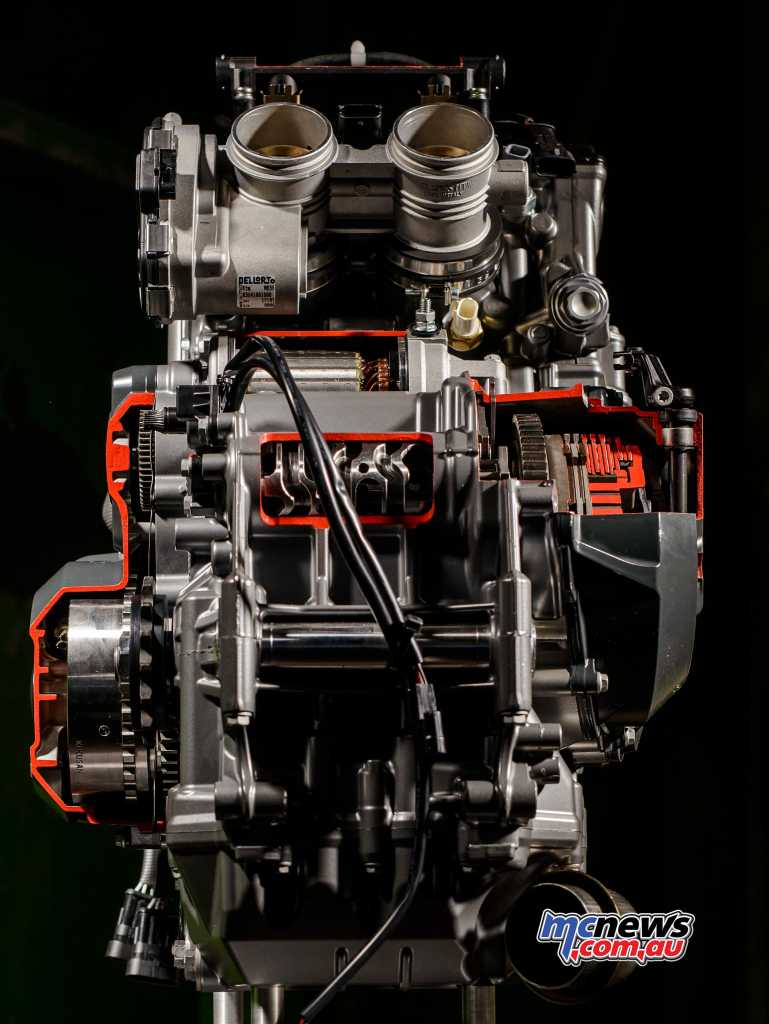

The crankcases are high-pressure cast and the open-deck cylinder bores were then milled and honed to fine tolerances directly into the cases before being Nikasil lined. There are no liners as such, or the need for a base gasket.

The cases split horizontally, rather than vertically, and the engine forms much of the backbone of the whole motorcycle as a stressed member. This is combined with the tubular welded chrome-moly frame to arrive at what, after lots of trial and error, KTM has judged the best balance of flex and rigidity.

To help keep the cases as small as possible one of the two counter-balancers is mounted in the cylinder head and driven by cam-chain. The advantages of the leverage achieved by it being mounted so far away from the crank means it can be much smaller than conventional designs. As the engine is a stressed member, it was important the engine be as smooth as possible and from the riders seat I would say they have achieved that goal as any vibes are imperceptible.

In that one-piece cylinder head reside a pair of camshafts that activate DLC-shod finger-followers. That Diamond-Like-Carbon coating is also employed on the pins of the three-ring forged pistons that swing through a 65.7 mm stroke off a forged one-piece crankshaft via sophisticated ‘cracked’ connecting rods. It helps that along with a large heat-exchanger/radiator business and WP suspension, KTM also owns Pankl, a renowned maker of high-end rods and pistons.

The power-assist slipper clutch drives through to a six-speed gearbox stacked behind the engine, again for space constraints. The reduced engine height via that system allows for modest seat heights, while retaining plenty of ground clearance. Both the gearbox and clutch work faultlessly.

Dell’Orto supplies the 42mm throttle bodies which have a straight shot through to the intake ports. The spent gases exit via a stainless-steel exhaust system which uses the space created inside the long swingarm to fit a sizeable pre-muffler, which then exits into a single small traditional muffler on the right-hand side of the bike. Again, this is made possible by the compact size of the engine.

An optional Akrapovic muffler provides more aesthetic charms than auditory pleasures. It doesn’t actually sound all that different to the standard muffler which provides a fairly raucous soundtrack.

I think only a full system with a different pre-muffler design would really differentiate the sound from standard. Luckily it actually sounds pretty good, so you’re probably better off saving your pennies for something else.

The semi-dry sump, with a forced lubrication system via two oil pumps and an oil cooler, provide the 10W-50 Motorex Power Synth lifeblood.

CLICK BELOW FOR PAGE THREE…