If ever a factory was lucky, it was Norton in 1950. Insular, old fashioned and dominated by the dour, conservative Joe Craig, Norton relied on racing success to sell its road bikes and by the commencement of racing after the war, it was in dire trouble.

By 1949, Norton’s flagship Grand Prix race bike – and therefore its single most important marketing tool – should have been consigned to the museum. The ohc Norton was already ancient and owed a huge amount to Walter Moore’s original 1927 design. Worst still, the engine wasn’t state of the art, even when it was first drawn!

By 1949, Norton’s flagship Grand Prix race bike – and therefore its single most important marketing tool – should have been consigned to the museum. The ohc Norton was already ancient and owed a huge amount to Walter Moore’s original 1927 design. Worst still, the engine wasn’t state of the art, even when it was first drawn!

Running against the Norton were a mass of advanced four and two cylinder bikes, as well as far more sophisticated singles from Moto Guzzi. In short, Norton was dead in the water.

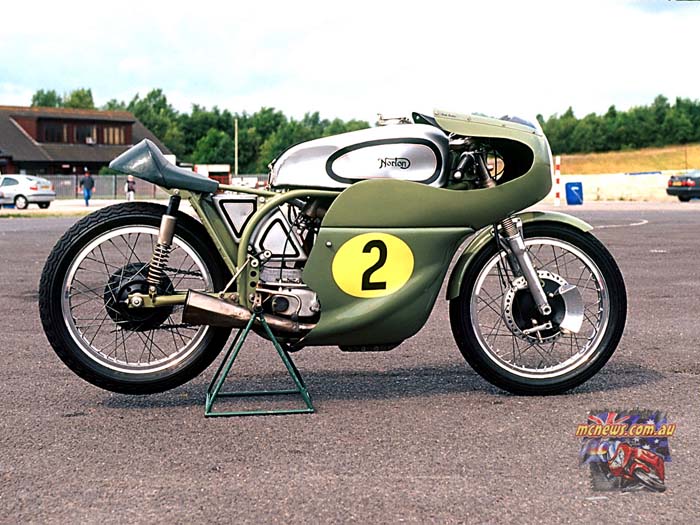

Then, in January 1950, Norton was gifted the design which was to save them. The talented McAndless brothers had produced an all welded, duplex frame with pivoted rear fork, suspension. Norton’s existing ohc engine slotted into the new chassis and, at a stroke, made every other motorcycle frame obsolete. This ground-breaking design was simply gifted to Norton and became the legendary “ Featherbed” framed “Manx”.

The reasons for the obsession with the Manx name was simple. The Isle of Man TT races were worth more in prestige than every other major event combined – more even than a World Championship. What the TT demanded, and the McAndless frame provided, was high-speed stability. So impressed was Norton’s team leader, Harold Daniels, with the new chassis that he described it as a “…featherbed ride” – and the Norton “Featherbed” frame was promptly born.

Even so, the new frame would probably not have been enough to rescue Norton were it not for two other strokes of sheer good fortune. First, Leo Kusmicki joined the company. Leo came to Britain as part of the Polish Free Air Force and stayed on after the war in a very menial position at Norton until someone discovered that he was one of Poland’s leading experts on internal combustion engines. First, he re-designed the 350 engine so that the power rose from 28bhp at 7,200rpm to 36bhp @ 8,000 revs. Later he did the same thing with the 500.

He was a modest, self-effacing engineer and took no credit for his work – which suited Norton race team manager, Joe Craig, perfectly.

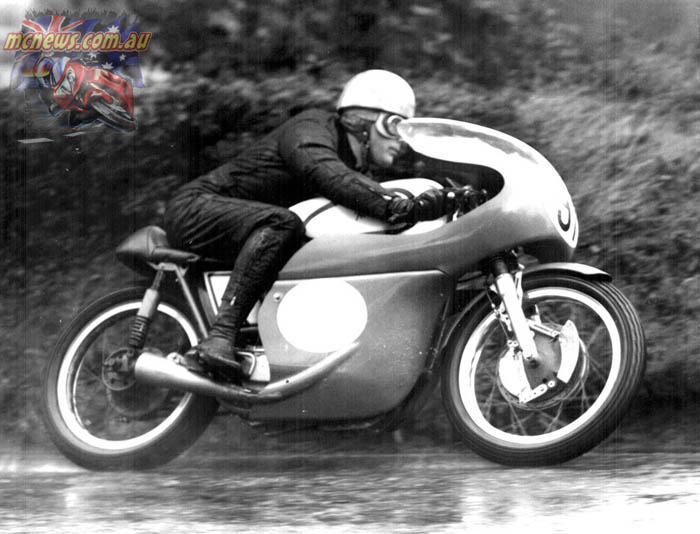

Then came the young Geoff Duke and, with him, Norton’s second giant sized slice of luck. The Manx Norton suited Duke to perfection. As a result, Norton’s ancient engine was given a world championship winning boost.

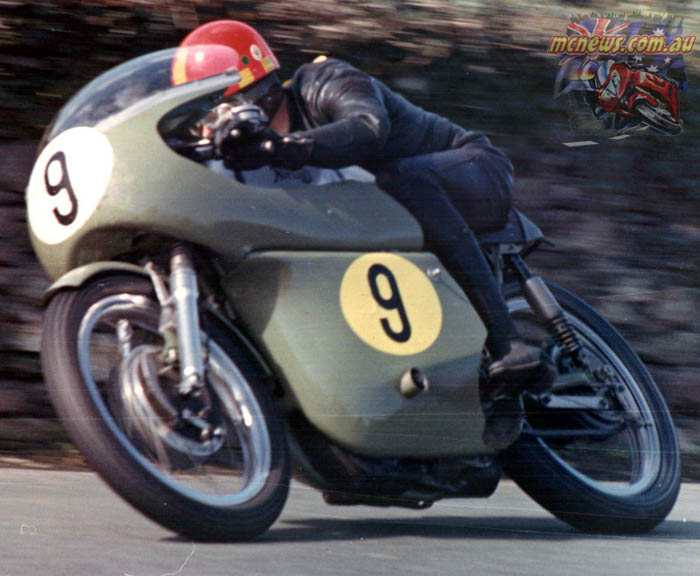

The Manx also became the tool of choice for professional racers the world over. If the revs were kept below 7,500 then a Manx could be raced at top level week in and week out earning a living for many on the Continental Circus: it was truly the tradesman’s ute of the racing world.

In doing so, the Manx also led the Japanese down a complete blind alley. Much of the quality of the handling comes from the fact that the engine, with its huge heavy flywheels, sits down in the duplex frame giving a tremendously low centre of gravity. When the same widely spaced duplex frame had two-stroke twins, and fours, housing it – the handling became very questionable and far from the Manx legend of stability and smoothness.

Riding a Manx today is still a magical experience. A Manx is huge for a racing motorcycle and once the rider is buried in the immense five and a half gallon (25 litre) TT tank, the bike holds a racing line with effortless tenacity: truly it is a featherbed ride. In its heyday, ridden on rough road circuits, a Manx must have been worth its weight in gold.

And even in the new millennium, the legend lives on. It is still possible to buy a brand-new Manx Norton straight off the shelf.