Around the world with The Bear – Part 22

The King of Every Kingdom

Around the world on a very small motorcycle

With J. Peter “The Bear” Thoeming

We didn’t – quite – make it to the middle of the Sahara. But we did find the world’s biggest mosquitos with the bluntest stings!

Algeria

Then the ‘route rapide’ of the map turned out to be the ‘road lente’, because it was less than half finished and we got to Tlemcen tired and dirty.

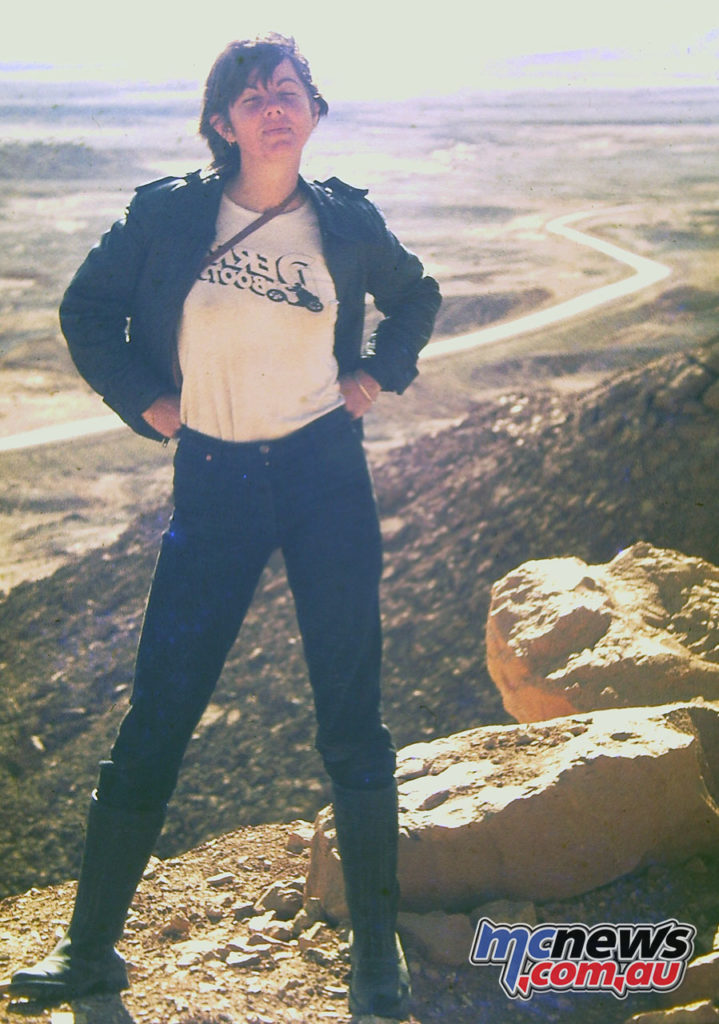

It took ages to find the campground; none of the locals seemed to know it existed, but when we did find it, it was comfortable and free – the only real drawback was a watchdog that delighted in untying people’s shoelaces and chewing through tent ropes. I collapsed again as soon as the tents were up, still feeling ill, and things started getting heated again. Neil insisted that we split up right there and then. He was right, too – if it isn’t working, don’t drag out the agony. We slept on it, and I think he was a little surprised when I started sorting out the gear in the morning. We divided the equipment and Annie and I, on a rather overloaded Yamaha, set off down into the Sahara. By ourselves.

I collapsed again as soon as the tents were up, still feeling ill, and things started getting heated again. Neil insisted that we split up right there and then. He was right, too – if it isn’t working, don’t drag out the agony. We slept on it, and I think he was a little surprised when I started sorting out the gear in the morning. We divided the equipment and Annie and I, on a rather overloaded Yamaha, set off down into the Sahara. By ourselves.

Feeling very much at peace with the world we buzzed across northern Algeria, with a short stop for coffee, and on into the greening countryside. Spring was in the air, people waved to us and we swept around the tolerably well-surfaced twisting roads in a thoroughly good mood.

Then half the gear we had balanced precariously on the back of the bike fell off – we lost our spare visors, Annie’s shoes and some food, but we weren’t particularly perturbed. Even the obstinacy of the police in Tiaret and Songeur didn’t bother us much.

The tourist office had assured us that these worthies would point out places to camp where there were no official sites, but all they would do was direct us to a hotel. ‘You are rich Europeans, you can afford it.’ Pleas of antipodean motorcycling poverty fell on deaf ears.

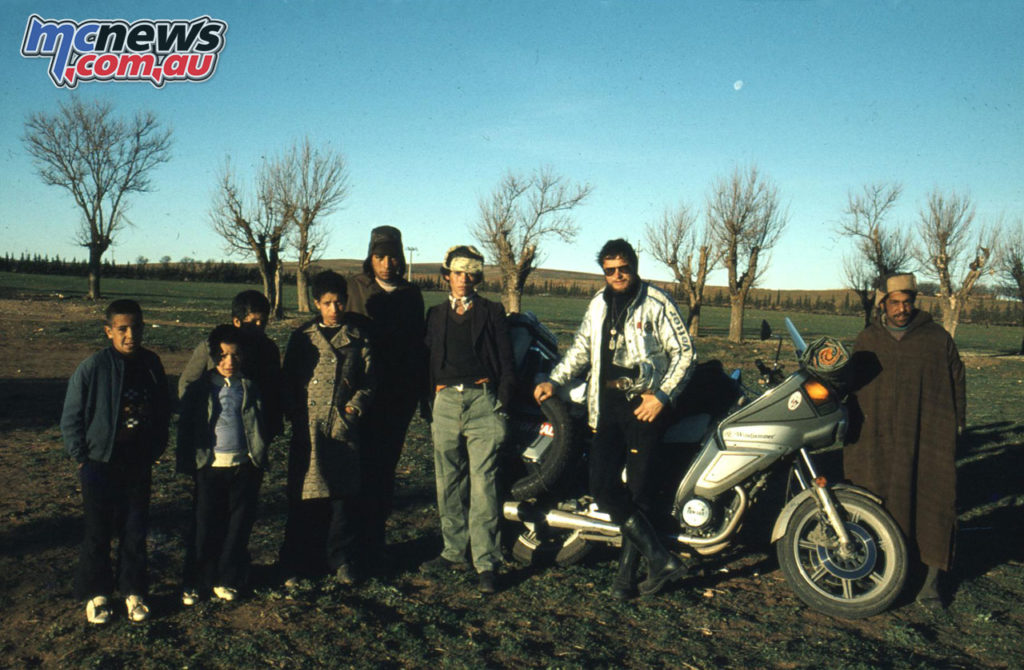

But it was all for the best. A farmer just outside Songeur was considerably more helpful; not only was he glad to offer us a place to pitch our tent, but he supplied us with milk and eggs and refused to take any payment. The whole family cheered us as we rode away in the morning. Algeria was turning out to be a much more hospitable place than it had been painted in Morocco.

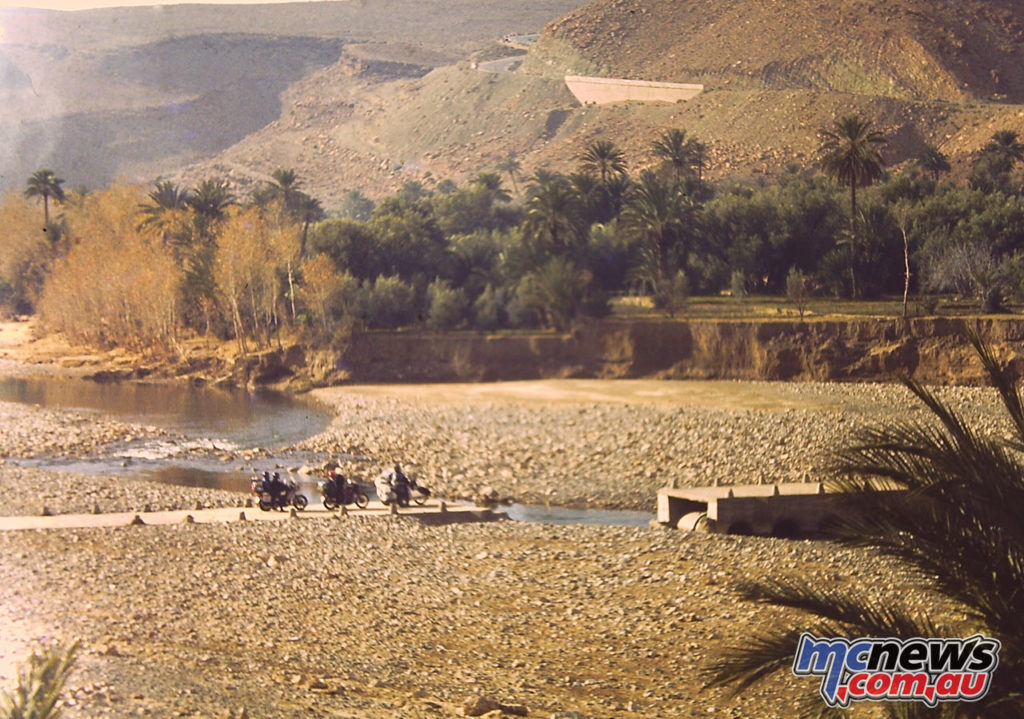

It was getting noticeably drier now, and as we neared Laghouat we entered the desert proper. Vegetation, which had been scarce for a hundred miles or so, disappeared completely and so did the few flocks of goats and sheep; only the camels remained.

Shops became scarce, too, in the few towns we saw and we found it difficult to buy bread. On this day Annie finally got some in a restaurant in Laghouat.

The Saharan roads weren’t bad, but roadworks meant frequent detours through deep sand which were rather trying. The bike handled them well considering it was now loaded up with all our camping gear, food reserves and 30 litres of fuel and water, but the sand was still a strain.

We were glad to see Ghardaia, our first real oasis, and its jolly but expensive campsite. We even popped up to the Big Hotel and had a drink. Considering how much wine Algeria produces it is damn hard to get any in the country itself.

One French traveler had a copy of the Fabulous Michelin 135 – the map of the Sahara crossing that’s been out of print and totally unobtainable for years – so I borrowed it and made a few notes in my diary; then it was on to El Golea.

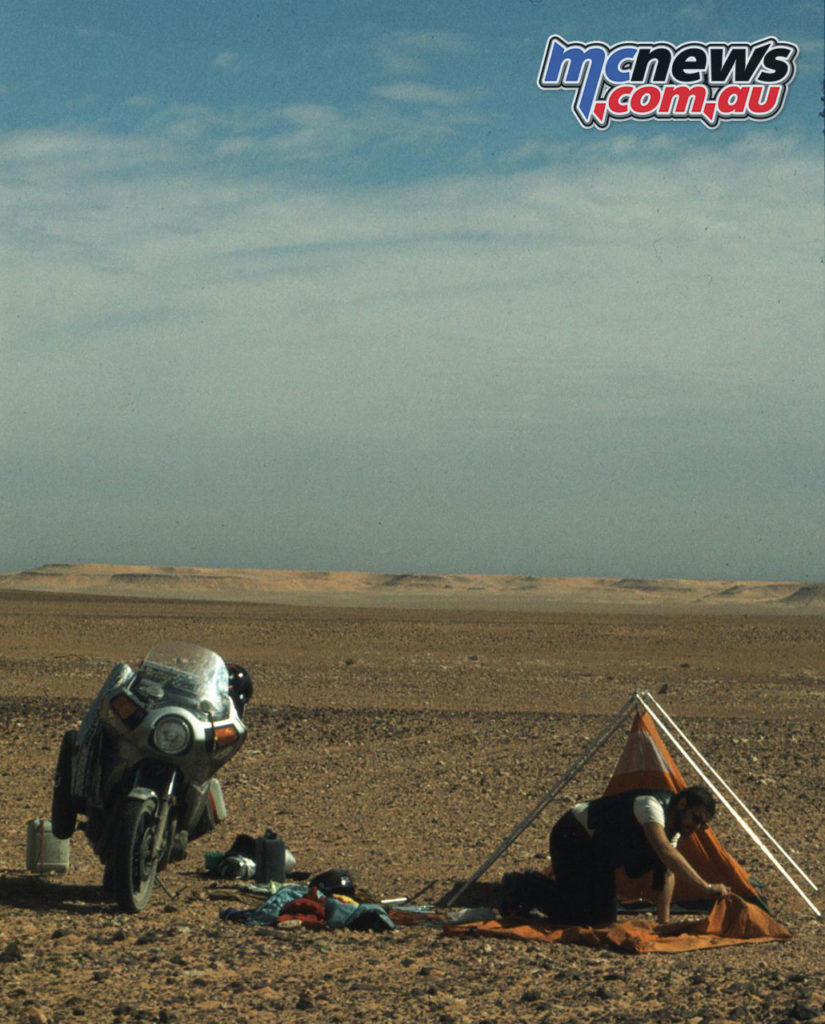

The desert scenery, which was flat, without hills or dunes, and with rock-covered sand to the horizon was rapidly becoming boring. The one bit of relief on this leg was an enormous golfball on an even more enormous tee just before El Golea – it turned into a microwave repeater when we got close.

There was more flatness the next day on the way down to Ain Salah. I was a bit worried about the road surface before lunch, but a meal made all the difference and I relaxed in the afternoon. Food is an excellent medicine for the jitters.

The truckies down in the desert were painfully polite, and would pull off the narrow tar when they saw us coming. The only problem was that once on the dirt they would then throw up an impenetrable screen of dust, which hid the road, so you never knew if there was another truck behind the first. If there had been we would have been decorating his radiator.

‘Where did you get the flat motorbike motif, Abdul?’ ‘It just came to me one day….’

The bike returned nearly 49mpg (imp) on this leg, the best it did on the entire trip, which was a testament to the flatness of the Sahara. Short of hills it might have been but the road was bumpy with shallow potholes, no more than an inch deep, which I learnt to ignore.

Ain Salah was a strange town; built of mud, or concrete covered with mud, it sat in the desert like a low rock outcrop. Where did they get the water to make mud? Aside from a half dozen lackadaisical cafes, it seemed to lack shops, even the markets selling only oranges and carrots.

Despite its isolation – it must be just about in the exact middle of the desert – Ain Salah is a cosmopolitan place; I guess they get all types coming through. We were warned not to camp in the ‘palmeries’, the palm plantations, because of the mosquitoes. They got us anyway, despite the fact that we sought out a little stand of palms way out in the middle of the sands; Annie returned to the tent badly bitten after answering the call of nature.

We held a council of war the next morning, and decided that enough Sahara was enough. There is only one road down through the desert and you must return the way you came. That would have meant looking at the same flat nothingness for an extra three or four days, and we decided we’d rather spend the time somewhere more exciting.

Then we tried to ride out. The back wheel of the Yamaha simply dropped through the crust and spun uselessly. We unpacked the bike, removing everything we could including the panniers, and then Annie pushed while I revved the bike as hard as I could. Slowly it began to move, and then it almost jumped back up onto the crust and I rode like blazes for the sealed roadway.

On the way back the little palm-lined campsite in El Golea sheltered us for a while, and we explored this huge oasis and its surroundings – Annie even tried out the bathhouse, but wasn’t impressed. One afternoon, a Land-Rover with two Australian women aboard rolled up. One of them got out and said, ‘Geez, I’d give my soul for a cold beer.’ We directed them to the one ‘good’ hotel in town which had stocks of this foreign substance.

Our return to Ghardaia was uneventful – more sand and rocks – and we had a look around this “second Mecca”, so called because parts of the valley are still closed to non-Muslims.

Then we set off for El Oued and the Tunisian border, and rode straight into the teeth of a sandstorm. By the time we had turned east it had become a crosswind and was throwing the fully laden bike all over the road – on one memorable occasion, even into the deep roadside sand. Coupled with the limited visibility of about 20ft it was too much for me and we turned around.

The most excruciatingly boring day followed as we sat in the tent and listened to the wind howling outside. After the third game of Scrabble and a couple of Mastermind we just sat there and stared at the canvas. But it had settled down the next morning and we made good time across – you guessed it – more flat desert.

But near El Oued the country changed and soon we were riding through, and sometimes over, enormous sand dunes. This was the Great Western Erg, the sandy desert you see in the movies.

By the side of the road, the telegraph wires often disappeared into the tops of dunes, only to reappear on the other side. Communications must be dire. We also saw date palms and herds of camels, and decided that this was much more like it. Why couldn’t the whole Sahara look like this?

Our troubles were not over with the end of the sandstorm. The bureaucratic calm was about to engulf us on the Tunisian border.