Around the world with The Bear – Part 23

The King of Every Kingdom

Around the world on a very small motorcycle

With J. Peter “The Bear” Thoeming

In the last instalment The Bear has just reached the Tunisian border, and was now stuck at the border with no visa, no money and no food. What the hell. Let’s party!

Tunisia

When we reached Hazoua, the Tunisian border post, a slight problem emerged. The tourist bureau leaflet had assured us that visas were issued at the border, but the sergeant on guard thought otherwise. ‘Not possible.’

I told him about the leaflet and he smiled gently and said, “Ah, the tourist bureau, it is their job to get people to come to my country but it is my job to keep them out.”

I told him about the leaflet and he smiled gently and said, “Ah, the tourist bureau, it is their job to get people to come to my country but it is my job to keep them out.”

Problem. We couldn’t go back, as our single-visit Algerian visas had been cancelled half an hour earlier at the Algerian border, and we couldn’t go forward because this officious idiot wouldn’t let us. We couldn’t really stay there, either. Without money changing facilities or a shop for even the most basic necessities, Hazoua didn’t really make it as a campsite.

But one of the skills you develop if you travel a lot is knowing when to shout and when to whisper and I decided this was a shouting situation. So I waved my press card and introductory letter at the sergeant.

The letter, from Middle East Travel Magazine where I had been art director, was in Arabic and impressed the guard sufficiently for him to get on the radio. He came back and said, perhaps, but it would take three days. We sat down to wait. I was fairly confident they wouldn’t let us starve, and I was right.

One of the guards saw me rubbing Nivea (another sponsor, thank you!) into my hands and delightedly shouted, “You are woman! You are woman!” I invited him to look at the monster that our XS11 Yamaha had become with all of its fairings and our luggage. ‘Could you ride that? No? Then beware whom you insult.’ He gave us half his dinner, and some of the others kicked in as well.

Then followed a hectic night for all. The guards were nervous and afraid of the Lybians, who had attacked the nearby town of Gafsa a few days earlier, and they spent the night prowling around with loaded guns and flashlights.

We slept first on the veranda and then, at the guards’ invitation in the Customs post, more afraid of those guns than of the Lybians. A false alarm involving a Belgian camper van which had scared the sentries lightened the atmosphere a little as the terrified Belgians were dragged in at gunpoint and interrogated.

“Do you think we are fools? What were you doing out there? I do not care if you are a policeman!” North African French is relatively easy to understand because it has a small vocabulary and no grammar whatsoever, so we could follow all this. It was nevertheless confusing; why pick on these people? One of the guards came out and winked at us. “Belgians!” he grinned.

Things looked better in the morning. The Chef du Poste (who is the boss, not the cook) arrived and cut through some of the red tape, and with visas in our passports there finally seemed to be a way forward. But we needed duty stamps for the visas, and they were obtainable only in the next town.

“We shall do this,” said the Chef du Poste. “You,” pointing at me, “will take the motorcycle to get the stamps. She,” pointing at Annie, “will remain here.”

‘Ah, no.’

“Then we shall do this. You and she and this guard will go on the motorcycle to get the stamps.”

‘Ah… no. Why don’t we just ride to the town and get the stamps? Of course we will return.’

“Ah, no. We shall do this. The guard with your passports will take the bus. You two will follow on the motorcycle. You will pay for the stamps and the guard will give you back the passports.”

‘Ah, yes. Thank you.’

“No, no, it is nothing… welcome to Tunisia.” All of this in ‘the broken North African French, of course, mine considerably more broken than his.

There was one more hurdle, however, in the form of a police checkpoint just outside town. The bus was checked and went on. Then it was our turn. As I tried to explain in my combination of schoolboy and gutter French that the passports the cop wanted to see were on the bus (voila, les passports, er, marchons dans le autobus!).

He became more and more annoyed and began to toy with his sidearm. Fortunately, the guard on the bus remembered us around about then and made the bus turn back. He was abused for inefficiency by the cop, who then let us pass with a big, toothy grin.

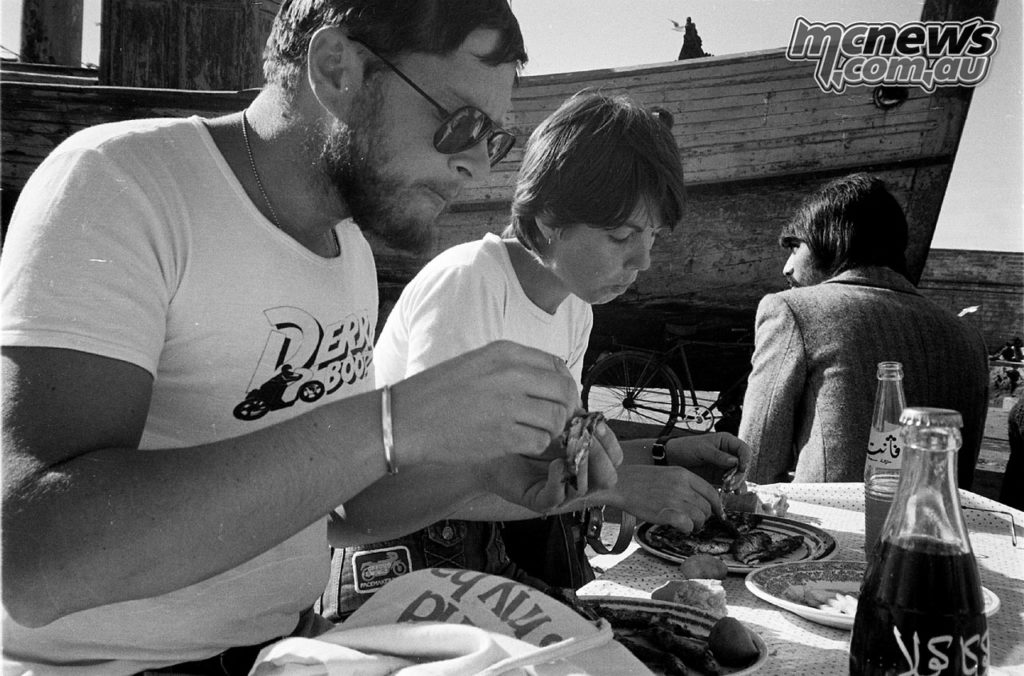

Tunisia didn’t really turn out to be worth all the trouble. We rode up to the coast at Nabeul through uninspiring country, camped and went in to Tunis to pick up mail and book the ferry to Sicily. Annie scouted out a replacement gas bottle for our stove, which was a relief. Nice to be able to do your own cooking.

We moved to a hotel in Tunis for our last night, because the ferry left at 6.30 am and the nearest campsite was two hours from the port. The Hotel Medina was nice; our hosts insisted that we park in the lobby, which I’d intended to do anyway. Then we went out and bought some English newspapers as well as pate, salami and bread, and had a feast of eating and reading in our room.

We explored the medina as well and found it pretty if a little tame, discovered the excellent produce markets and then slept until one am. Then the alarm on Annie’s little calculator, the desk clerk and the muezzin from the nearby mosque woke us simultaneously.

Getting the bike into the hotel lobby had been easy with a dozen helping hands, but now that it was just Annie, the desk clerk and me it wasn’t quite so easy to get it out. After a 36-point turn – scuffing their paintwork with my front tyre on every one – I managed it and we rode off down to the ferry followed by the desk clerk’s blessings.

While we were waiting aboard the big Yamaha in the light, sprinkling rain for them to open the gates, an XS500 arrived… then an XL125… then two bicycles. I kept expecting someone on a skate board. After an elaborate check of papers, which failed to turn up the fact that we had overstayed our visas, and a confused Customs check, we finally rolled aboard. Back to Europe!

Italy

The ferry to Trapani wasn’t exactly the QE2, but it got us there; everything was rather shabby and the bar and restaurant were expensive and generally closed. In the third class saloon, where we made our home for the 12 hours of the crossing, there was strict segregation – the Arabs sat on one side, we Europeans on the other.

The curious thing was that you didn’t actually see this division happen – it just developed. When we first sat down, there was an Arab family sitting near us, then, as more Europeans arrived and sat on our side, they moved.

We spent most of the crossing playing cards with the French guys riding the bikes we’d met at the gate. True to form, these two let me struggle along in my idiot French until they wanted to explain something about the game we were playing – and then they both suddenly spoke passable English. The French are hilarious; they always do that sort of thing.

We spent most of the crossing playing cards with the French guys riding the bikes we’d met at the gate. True to form, these two let me struggle along in my idiot French until they wanted to explain something about the game we were playing – and then they both suddenly spoke passable English. The French are hilarious; they always do that sort of thing.

The Immigration check in Sicily must have been carefully designed for the absolute minimum in efficiency, but the Customs check that followed was considerably keener – it involved our first encounter with drug-sniffing dogs. One of them, a cheerful hyperactive German Shepherd, was much more interested in chewing our tentpoles than in looking for drugs. I politely asked the handler to restrain his beast.

Then it was out into the chilly, wet evening and up the autostrada to Palermo. Sicily in the failing light was almost unbearably picturesque, although I’m sure I would have enjoyed it more had I been warm and dry.

We reached the ‘Pepsi Cola’ campsite just as it was closing and the padrone took us into the office and poured us a brandy before we got down to the signing-in formalities. Sicilians are very perceptive people.

It dawned wet and cold, so we inserted ourselves into our Alaskan suits and MCB boots – waterproof boots are a real blessing when you get several days of rain – and went exploring. The site watchman warned us to beware of pickpockets in Palermo, but apart from the post office giving us change in stamps rather than cash we weren’t robbed.

You can never be sure what you’ll get when the Mafia builds your highways – as you’ll find out next instalment.