Where have all the old bikes gone? – With Phil Hall

My other hat apart from my motorcycling one, is my motoring one and it was, in fact, my only hat long before I discovered motorcycling in my mid-20s.

As a child I was obsessed with cars and car racing and I followed motorsport slavishly, especially once Jack Brabham won the first of his three world championships in 1959.

In the early ’70s professionalism started to rear its head in car racing and the Moffat/Brock thing just didn’t do it for me.

Formula 5000 was dying and the Tasman Series, where F1 drivers came out to Australia for the Christmas holidays and raced cars around our tracks, was but a distant memory.

Buying my first bike in 1974 steered me in a different direction but it was over a year later, in early 1976, that I attended my first bike race meeting.

Fortunately for me it was the Australian TT at Laverton in Victoria where Australia’s Kenny Blake famously defeated the legendary Giacomo Agostini and won the hearts and minds of everyone at the track.

However, I still maintained an interest in four-wheeled sport and the cars that make it up, and that interest has persisted ever since.

Watching all of this transpire, it has always delighted me to read about and hear of the way that enthusiasts of all kinds have gone about finding, preserving and restoring the great cars of the era that I enjoyed watching as a teenager.

Jack Brabham’s original speedway car, built in 1948, is still around and does regular duty at demonstration meetings.

Our museums have large numbers of cars that competed with distinction at the Bathrust enduros and there are countless garages around the country where precious gems of our motor racing past reside, brought out from time to time for shows and meetings like the Muscle Car Masters.

Because, when you think about it, unless owners of the cars have been exceedingly careless over the years, it isn’t especially difficult to preserve a car.

Even though we read epic tales of how famous cars have been discovered, moldering away in a shed somewhere, and been brought back to life by enthusiasts who go to extreme lengths to reunite all the bits that originally made it up, most “barn finds” are still basically intact, if run down and neglected.

Now there is a caveat here that applies to both bikes and cars and to which I will return in some more detail at the end of the article. The caveat is that we are discussing competition vehicles here and nothing gets older faster than a race bike or a race car.

They get crashed , repaired, crashed again and usually, at the end of the season when they are no longer competitive, they get sold to a new owner who continues the cycle with the vehicle all the time continuing that downward spiral.

So the present situation where we do see great bikes from the era on show, they rarely represent what the bike actually looked like in the day. More about this later.

As far as the great bikes are concerned we have a significant difficulty that is not present when we discuss great cars.

You see, it is much harder to break up a race car, simply because it is such a complex vehicle compared to a bike.

A bike is just a frame, a motor and two wheels. The ancillary bits like bodywork and electronics can be disposed of very easily indeed, so what was a sparkling new machine at the start of the season can be easily broken up and its attendant parts be flung to the four winds by season’s end. This is even more so if the bike has had a hard life throughout that season.

The other problem is that, with some notable exceptions, most owners of what we now regard as important or historical bikes, had no idea at the time that they were so or that they would be looked back on with affection and interest years on.

Let me try to explain. In the ’70s the Yamaha TZ range of motorcycles, most notably the 250 and 350 iterations, were as common as you can imagine.

The other day on Facebook someone posted a scan of an entry list for an Unlimited race in the ARRC at Oran Park in 1978.

The entry list for the one race was well over 50 riders and the vast majority of them were entered to ride on a TZ350. 250’s were, by regulation, prevented from entering in Unlimited races though on some circuits they were as fast as an Unlimited bikes.

I well remember the aggro that ensued when the organisers in Canberra in 1980 refused to let Paul Lewis start in the Unlimited race on his 250 even though he was setting times in his races that bettered the times being set by the big four-stroke bikes.

Anyway, back to the TZs. In the day, a brand new TZ350 cost $2800. It came with a comprehensive spares kit that could last for more than a season provided the owner looked after the bike and didn’t have any major mechanical issues.

All that was required was a careful tear-down, re-assemble, a set of good tyres to replace the Japanese rim protectors that it came with from the factory, and you were ready to go racing.

It wasn’t surprising then that there were literally dozens of TZs on the grid at every meeting, even more so if you threw in the 250 models which were even more plentiful as they were cheaper and could be ridden in three classes (250, 350 and Senior – 500).

As such they were pretty much considered as a disposable item. You on-sold at the end of the year, bought the newer model and started again.

The new owner would often keep the bike a little longer as they probably weren’t able to afford a new bike anyway and so the downward spiral continued. Today a very small handful of TZs are still in existence, where did those hundreds of race bikes go?

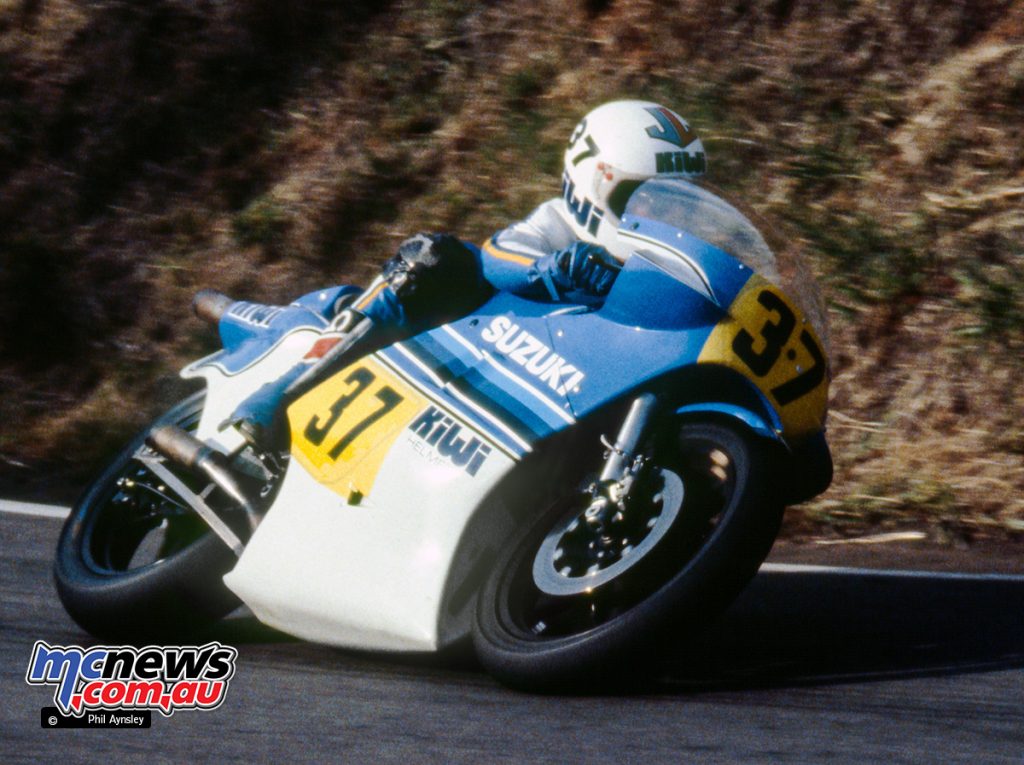

And that is just the pukka, two-stroke racing bikes. Where are all the RG500 Suzukis now? Where are the smaller number of TZ500s that came here in the late ’70s?

Oddly, it seems that their bigger brother, the TZ750, has been somewhat better at surviving with the big banger undergoing a resurgence of interest in the last five years or so.

But where are all the four-stroke production bikes that won the prestigious production races back then? Where is the BMW that took Kenny Blake and Joe Eastmure to victory at Amaroo Park in 1977?

Sadly, the majority of these bikes have long ago been scrapped, on-sold when their racing careers were ended, put back on the road by their new owners who, for the most part, had no idea that their bike had an illustrious past.

Thankfully, the scene is not all gloomy. While the vast majority of the great and significant bikes from the era are long gone, some of them have been preserved and are still around for us to see, hear and enjoy.

Over the last few years I have been trying to trace some of them and it is fascinating what sort of answers you get if you ask the right people.

In February 1981 the late Greg Pretty and current “works” Yamaha mechanic, Gary Coleman, won the Coca Cola 800 endurance race at Oran Park.

They did it on an XS1100 Yamaha that, after a visit to Malcolm Pitman’s workshop in Adelaide, emerged with its standard shaft drive system removed and a chain drive system in its place.

There have been several other chain drive XS’s built since and one still races in historic racing, but did the original “Coke” bike survive? The answer is that it did.

It lives in the garage of a private collector still and, though it is never seen in public, it is comforting to know that it has been preserved.

The Triple M Honda CBR1100 that took Wayne Gardner and the last Andrew “AJ” Johnson to victory in the sodden Castrol Six Hour race in 1980 is on permanent display at the National Motor Racing Museum at Bathurst and the majority of the Kawasaki two-stroke motorcycles ridden by the late, great, Gregg Hansford are gloriously preserved and still ridden by a collector in Brisbane to whom we owe a great debt of gratitude.

Last year, after gathering dust in the corner of a Melbourne workshop for more than three decades, the Syndicate Kawaskai saw the light of day and was taken to Broadford for display at the Penrite Bonanza.

Fans who remember AJ wrestling the unmanageable beast around were very misty-eyes when it was wheeled out.

And there are many, many more, all of which have some place in our rich racing history. But, as well as finding them there is another problem and that is the problem of over-restoration.

Remembering that we are discussing racing bikes here, it is sad to see that these wonderful examples from yesteryear are often being restored to a condition which they never enjoyed at any stage in their racing career. Surely if the bike was not a polished masterpiece when it was in its hey-day, it should not be now?

In the coming months I’d like to revisit this topic and discuss some of the examples of great racing bikes that have survived or have been rescued and preserved. The trail takes you through some strange pathways, I can assure you.

It goes without saying that, if any of our readers know where some of these great race bikes are still, it would be great if you let us know.