Where have all the old bikes gone? Part 2 – With Phil Hall

Where have all the old bikes gone? Part 1.

Some time ago I penned an article with the above title in which I wondered out loud what had happened to all the old racing bikes that I remember from when I started watching the sport in the mid-’70s.

I noted that the majority of them had no doubt been scrapped as this is the nature of race bikes, being seen even in their time as being expendable objects.

You see, there is nothing that goes out of date faster than a race bike. In fact, it’s almost out of date as soon as someone buys it or builds it and starts to race it. And, even as it is being raced, its obsolescence is becoming apparent.

As an aside to illustrate this, this concept goes right to the top, where even MotoGP bikes are outmoded and shifted aside for a newer, better model during a season, sometimes with frightening regularity.

When I was closely following the sport I always derived a degree of amusement when, at the beginning of a new season, some up and coming rider would turn up at the first race meeting in the new year with a new bike (many used to, TZ’s were surprisingly affordable) which turned out to be an already well-known bike from the previous season.

There was always the assumption that, since someone had ridden it to great success in the previous season, such success would continue in the new season and in the hands of the new owner.

But, you know what? It rarely happened. A bike that had won dozens of races in the previous year mostly failed to visit the winner’s circle in the new year and it had nothing to do with the bike.

You see, there is nothing magical about a race bike. The most important and critical component of a race bike is the person who is twisting the throttle.

The bike may be fast, built to exacting specifications, have all the latest hot bits and have an outstanding pedigree but it won’t be a winner just because of these factors.

It will only be a winner if the new owner is capable of making it so. And many starry-eyed young riders continue to find this out even today just as they did back then.

It doesn’t take long for the disillusionment to set in and that shiny new second-hand bike soon becomes a third-, fourth-, fifth-hand bike in quick succession. But that’s not the only problem.

Even when the bike is still in the hands of its original owner, changes are being made, improvements (or otherwise) are being instituted and crashes and racing incidents are taking the gloss off the machine (literally).

Unless you have an unlimited budget, (and who has), your shiny new bike will arrive at the end of the season looking and being quite different to what it was at the start of the season.

As noted, race bikes are expendable items, and it was back in the ’70s when I first got into the sport that this concept started being seen (at least so it appears to me).

I just missed seeing the great Ron Toombs race but, by the time he started racing for TKA, the idea of racing a bike for more than one or maybe two seasons was becoming a thing of the past.

The Henderson Matchless on which Toombsie achieved fame and which he piloted to innumerable wins was refined and developed over many seasons. The new guard was, “replace rather than repair”.

So what did happen to some of those great bikes of the ’70s? Well, thankfully some of them survived the ravages of racing and of being handed down from owner to owner and persist even to this day, with the passage of time and the succession of owners, their stories become more and more interesting.

Some while ago I wrote an article about Robbie Phillis and I noted that the year that he spent at Milledge Yamaha as one of their two contracted riders was turbulent to say the least.

Some memories from that year are best buried but, amazingly, Robbie still has the TZ350F that he rode for the Victorian concern and it is still in the Milledge livery. What a survivor!

Speaking of Robbie, he also still has the GSX1100 superbike on which he won four successive Australian Superbike Championships, the bike only recently having been finally retired from active competition in the Historic class.

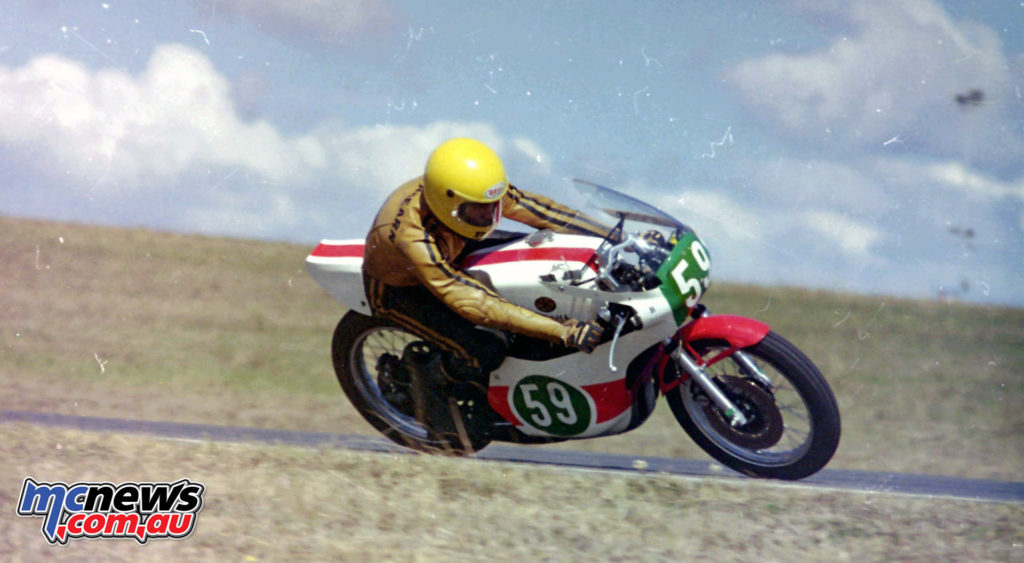

In that same article I also wrote about Ron Boulden and noted that my first sight of both he and Robbie racing was a “C” Grade day at Hume Weir in 1976. Robbie was on a brand new C model TZ and Ron was also on a TZ350. But Ron’s bike was a bit different.

Firstly, though I didn’t know it until much later, it wasn’t new. Though it looked it, such was the team’s standard of preparation, it had, in fact, passed through at least two owners hands before it appeared in the Welbank colours.

The frame was a British-built Maxton and it had been bought in England, raced there by Jack Ahearn and Rob Madden before being brought to Australia and raced by Boulden. Originally it had had an air-cooled engine but was fitted with the water-cooled engine by 1976. In Boulden’s hands it lasted just a bit over a season before being shifted sideways and then out.

When Ron’s dad bought him a new TZ250C so that he could compete in more races, Ron campaigned both the bikes but, late in 1977 (from memory) the engines were swapped with the 350 going into the newer, cantilever frame and the 250 going into the older, twin-shock Maxton frame. Such was the controlled obsolescence of race bikes to which I have already referred.

The exact history of the original Maxton bike is unclear to me (though I am sure someone will know it) and, to all intents and purposes, it disappeared as old race bikes do. Except that it didn’t.

Years later, just a few years ago, in fact, I attended the Barry Sheene Festival of Speed at Eastern Creek and was delighted to see a familiar name, Hindle. Yes, Glenn, the son of the great man himself, was racing a Yamaha, bearing his father’s famous #50 and was doing very well indeed.

A closer look at the bike in the pits revealed that it had an air-cooled 350 motor in a Maxton frame. Yes, Glenn’s bike is the ex-Boulden Maxton frame but with a return to its original specification.

And in a classic illustration of how everything that I have said so far is wrong, the bike continues to be campaigned and shows no sign of being retired! Of course, within the parameters of historic racing, the above comments about obsolescence are wrong; historic bikes are like Berger paints, they just keep on keeping on!

Now, I mentioned Ron’s other bike, the new TZ250C that became the 350 later on. Well, that bike has done a Berger paints as well because it, too, is still around.

Again, researching bikes and their history is a quirky business. It’s rather like whale-watching. Every now and then the whale will make an appearance but quite what it has been doing since you saw it last is somewhat of a mystery. Thankfully, the owners who are preserving some of these bikes from our history are fanatical people.

At the Australian Historics at Lakeside in 2014 I noted a bike in a very familiar colour scheme. Wollongong motorcycle dealer, Karl Praml and his then wife, Willie, did an amazing (and expensive) job fostering and encouraging the careers of young road racers in the Illawarra and two of the riders who more than repaid their faith were the two “Waynes.”

Wayne Gardner went on to become an international institution and Wayne Clarke achieved considerable local success before devoting himself to rider training and no doubt saving the lives of countless riders who benefitted from attending the courses that he ran.

And, Wayne Clarke bought the Boulden TZ250/350C model when Boulden sold it. In the Karl Praml Racing colours of blue and yellow, the two Waynes flew the flag for their sponsor with distinction, Clarke (from memory) running the bike as a 250 (someone will no doubt be able to confirm this for me),

And it was the Karl Praml colour scheme that attracted my attention at Lakeside. Conversation with the owner, Ant Sykes, from north Queensland, revealed that it was the ex-Clarke bike and that, by extrapolation, it was the ex-Boulden bike.

Now, unlike the Hindle bike which has gone though a number of iterations and bears no visual or engineering link to the 1976 model, Sykes’s bike is absolutely original and unmolested.

Totally unrestored, it could easily fit right back into a 250cc grid in 1979 or around there. The present owner has no plans to restore it or update it, preferring to keep is as a functioning time capsule and a reminder of days gone by. I applaud his decision.

It has been in Historic racing circles that I have started to discover that more of the great bikes from the era have survived than what I first thought, and more and more discoveries are being made as I research the subject more.

Some are just now emerging from hibernation (and, in some cases, restoration) and others have been out there all the time, going about their business without attracting undue attention. Some are even in museums where they will be preserved.

In many of these cases the bikes are too valuable to do anything with except display. The Henderson Matchless to which I referred earlier, lives in the National Motor Racing Museum at Bathurst, for example. The Jesser Triumph, on which Kenny Blake rocketed to fame in the early ’70s lives on in the MA Museum in Melbourne. Some of the old bikes are still here, but are in disguise (more of that in another article).

Sadly many of the great bikes are gone however, the natural attrition of racing having taken its toll. But, with the growing interest in historic racing as well as the business of restoration becoming more widespread, we still have the opportunity of seeing, and sometimes, hearing, the great bikes from long ago.