Movie review: “On Any Sunday” – With Phil Hall

On a fairly regular basis a question about motorcycling films/music arises on social media. It’s usually, “What are your favourite motorcycling films/songs?” and the answers are nearly always the same.

While motorcycles have featured in many movies from many different countries over the years, there have been very few valuable motorcycle documentary films. And, of those, fewer still have been accurate, informative AND entertaining. “On Any Sunday” (hereinafter referred to as OAS) meets all of these criteria in spades. It thus remains, despite its age, THE definitive motorcycle movie across all genres, and for very good reason. Firstly, then, some background.

OAS was released in cinemas in 1971. It was produced by the American film producer, Bruce Brown, who already had to his credit the string of super-successful and critically-acclaimed surfing films under the “Endless Summer” nametags. Brown was both the director and producer and relied upon the assistance of Steve McQueen in the area of production. McQueen, noted for his “tough guy” image in his action movies and also for his passion for motor racing (Le Mans – 1970), was also a passionate motorcyclist, having used his skills and expertise in the 1963 WWII drama, “The Great Escape”. It was nominated for an Academy Award in the documentary category in 1972.

Though the insurance company would not allow McQueen to do the now-famous jump over the barbed wire fence on a motorcycle (that was performed by Steve’s good friend and stunt man, Bud Edkins), he did ride many of the scenes that required bike riding in the movie. In fact, his skills were so in demand and his ability on a bike so much better than the crew’s stunt men, that McQueen was called upon to do much more riding and one scene features McQueen, dressed in a German uniform, pursuing McQueen, dressed in an American uniform!

So, when Brown floated the project of OAS with McQueen, he jumped at the idea.

The stars of the film are the two American professional motorcycle racers, Mert Lawwill and Malcolm Smith, and it follows (loosely) their various motorcycle competition endeavours through a motorcycle racing season. At the beginning we see Lawwill as the defending #1 plate holder in the AMA competiton and we follow him as his defence of his #1 plate starts to unravel through a myriad of mechanical failures and disappointments. We rapidly identify with him as a truly nice guy who somehow manages to have all the bad luck a racer usually has in a liftetime, crammed into one season, until we see him surrender the plate to Gene Romero at the end of the movie.

Smith, a professional enduro rider, is the comic relief, although his efforts on the bike are far from comic. We see his grinning visage under the helmet in desert races, The Baja 1000, motocross/road races, The Elsinore Grand Prix, hillclimbs, “The Widowmaker” and his chosen discipline, enduros, The International Six Day Trial at Escorial in Spain. As well, we see him and Lawwill and McQueen at play, trail riding, beach racing and generally messing around on bikes.

Along with the famous, the film features thousands of everyday motorcyclists doing what motorcyclists do. Sunday afternoon motocross on a mudhole local track, road racing at Daytona (with some glorious slow-motion sequences illustrating the poetry and the brutality of the sport). We see Malcolm Smith doing some truly dazzling things on an observed trials bike and an unnamed rider becomes the star of the famous $3000 signal fire sketch in the Baja 1000.

The film is 96 minutes long; long for a documentary of the time, but it crams so much entertainment into that time that it actually seems longer. The narration, by Brown himself, is laconic, laid-back (what would you expect from a guy who shoots surfing movies?) and never sensationalised like many American documentary efforts tend to be. The narration, in many cases, is significant for what is NOT said, rather than what IS. Brown asks at the beginning of the movie, “Why do motorcyclists do what they do?” but then he appears to “cop out” on the answer. “If you ask them, they just say they like to do it.”

Some have found that answer to be most dissatisfying, but almost exclusively, they have been non-riders! Of course, as the movie progresses, Brown shows his mastery of the art by allowing the motorcyclists’ ACTIONS to answer the question with an eloquence that words could not equal, and so, at the end, nobody is left in ANY doubt as to why we ride.

We learn a lot about motorcycling, and the racers themselves. We see how they will work long hours by making cuts in their tires, or grinding down a cam follower, all in order to gain some traction, lose a few ounces and increase their R.P.M.s. We learn most bikers are small, young men in their early 20s, and many of them making motorcycle racing a 7 days a week job. Most of the movie is about racing in North America, but we are also shown the suicidal sport of ice racing in Quebec, and an annual six day long cross-country race over brutal terrain in Spain, where you have almost no time to change a tire or rest. We see the land speed record (previously 250 m.p.h.) broken by 15 m.p.h (a truly hilarious sequence, in this writer’s opinion.)

There are so many highlights in this movie that it seems grossly unfair to single out one, but I must. My personal favourite isn’t the road racing segment, as you might expect, but the ISDT in Escorial, Spain, where we follow Malcolm Smith through six brutal and intense days of enduro competition. For top-drawer documentary filming, this must be about as good as it gets.

I must also mention the musical score by Dominic Frontiere. While sometimes trespassing very close to the “spaghetti western” style, he nevertheless accompanies the film with a score that always seems appropriate.

The final competition scene at “The Mile” is full of intensity. Unlike most American directors, Brown allows the ferocious accident involving Jim Rice to play out without any commentary whatsoever, restraint that deserves noting. And, if there ever WAS any doubt as to why “they” do it, by the end of the day’s competition, this doubt is removed completely.

The film finishes with an “at play” scene involving Smith, McQueen and Lawwill, messing around on a beach with their trail bikes. In the setting sunlight we see the comradeship, the exhilaration and the joy that can only be found in riding bikes with your mates. It is a classic sequence and a truly fitting one with which to end the movie.

In a movie that has become a cult, it is logical that all manner of “behind the scenes” information about the film is discussed even today, such is the fascination that it holds for motorcyclists all over the world. Like the Elsinore Grand Prix story. In order not to be banned from doing the race by his nervous Nelly studio mavens, McQueen enters it under the pseudonym of Harvey Mushman. As a result the “Who is Harvey Mushman” quiz is also a regular feature of Facebook discussion. It is common knowledge now that the Harley Davidson trail bike that Lawwill rides in the final scenes of the movie wasn’t a Harley at all but a Czechoslovakian CZ motorcycle, painted in HD colours. And a piece of trivia that I have never heard before (or since) is that the slo-mo crash at Daytona where the rider’s glove is seen flying through the air is actually of former #1 plate holder, Gary Fisher. During an interview for MotoPod a few years ago, Gary dropped this little gem and it was quite a surprise.

Bruce Brown is still alive as are Malcolm Smith and Mert Lawwill (of whom more a little later). Sadly, McQueen’s fast and loose lifestyle caught up with him and took him from us much too soon. OAS immortalises him for all motorcyclists, thankfully.

I stumbled across this amazing interview with Lawwill a few years ago (link below). The interview is over 30 minutes long and it reveals a side of Mert that most of us (myself included) would never have known. I do recommend that you listen to it as it shows the incredible depth of skill and compassion that Mert has brought to the engineering side of his life after racing. I was captivated when I heard it the first time and I have listened to it again in case I missed something. 34 minutes of your life that you will never regret.

Back to the film as I conclude. This film has everything; glorious scenery, amazing slow-mo sequences, humour, tragedy, mateship, insight, a “rider’s-eye” view of the sport and an amazing empathy for motorcycling from a director who, by his own admission, wasn’t a motorcyclist. For that honesty and integrity, Brown deserves the highest praise.

I have watched OAS dozens of times and every time I do, it is a joy.

Postscripts: There was a sequel to OAS that was made some years later featuring America’s speedway World Champion, Bruce Penhall. My advice? Give it a miss.

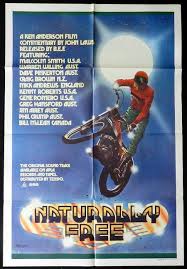

There was also an Australian version of OAS made in the mid 70’s called “Naturally Free” It was made to a similar pattern and was narrated by John Laws. It featured trials ace, Dave Pinkerton doing his thing in country shows, Warren Willing and Gregg Hansford racing at Ontario Motor Speedway in California and many other names of the day enjoying their motorcycling. A long segment of the Nepean Six Hour short circuit race is just too ocker to even contemplate but the glimpses of scenes that are all too familiar to those of us who lived in the era makes it well worth a look. It was made for commercial release but never went into the theatres apart from pre-release shows in some of the capital cities. It lives in the ABC archives (who knows why) but I think has been copied and loaded up onto some peoples’ private web sites. If you’d really like to see it, you’ll probably need to do some Googling.

In this case, the saying, “The original and the best” certainly holds true. If you haven’t watched it, you owe it to yourself to do so and I guarantee that you will watch it over and over again.