Royal Enfield Project Origin

Royal Enfield will be displaying ‘Project Origin’ as part of their anniversary celebrations, a faithful working replica of the brand’s very first ‘motor-bicycle’, giving riders a peak back to the very beginning. This was the very machine that built the foundations upon which Royal Enfield has based their enduring legacy of ‘Pure Motorcycling’.

The brand’s tagline, ‘Since 1901’ pays testament to the important concept of heritage and the past is to Royal Enfield, and ‘Project Origin’ embodies this sentiment, and came about after a challenge was laid down to the Royal Enfield design and engineering teams by Gordon May, Royal Enfield’s in-house historian, during a historical presentation to celebrate the brand’s 120th anniversary.

Part of the presentation focused on the very first prototype Royal Enfield motor-bicycle that was developed all the way back in 1901 by Frenchman Jules Gobiet, working hand-in-hand with Royal Enfield’s co-founder and chief designer, Bob Walker Smith.

As the motorcycle industry was not sufficiently well established to have its own dedicated exhibition back then, the prototype was consequently displayed at the Stanley Cycle Show in London, in November 1901. This was the very first time any two-wheeled engine-powered Royal Enfield had been displayed to the public.

Check out the ‘Royal Enfield Project Origin – The Missing Piece‘ video on YouTube for more insight into the rich history behind this model:

To date, no working model of this original motor-bicycle had been found to exist and consequently a major piece of Royal Enfield’s historical puzzle was missing. There were no surviving design blueprints or technical drawings which gave any usable reference to how the motor-bicycle was constructed.

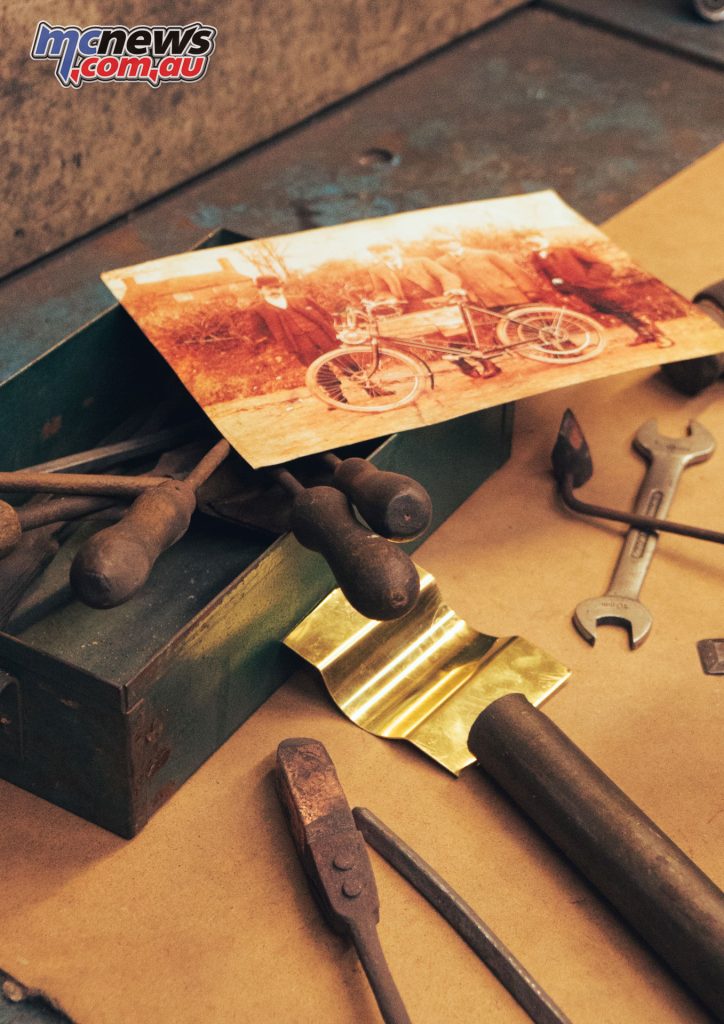

All that remained were a few period photographs, some promotional advertisements and a couple of illustrated news articles from 1901 that gave some basic graphic clues and information as to how the motor-bicycle would have looked and might have functioned.

The extent of the evidence to be guided by was slim at best, however this made the challenge being proposed to the Royal Enfield Team even more exciting – could the very first piece of Royal Enfield’s DNA be reconstructed in celebration of such a significant anniversary?

A team of passionate Royal Enfield volunteers was swiftly assembled and set to task on a journey of discovery and exploration, delving back through the history books to unearth as much information and century old knowledge as possible about the pioneering era of two-wheeled motorised transportation.

Working collaboratively between the teams at both Royal Enfield UK and Indian technical centres, as well as with Harris Performance and other experts from within the vintage motorcycling community, the treasure hunt to find all the pieces of the design puzzle started to build momentum.

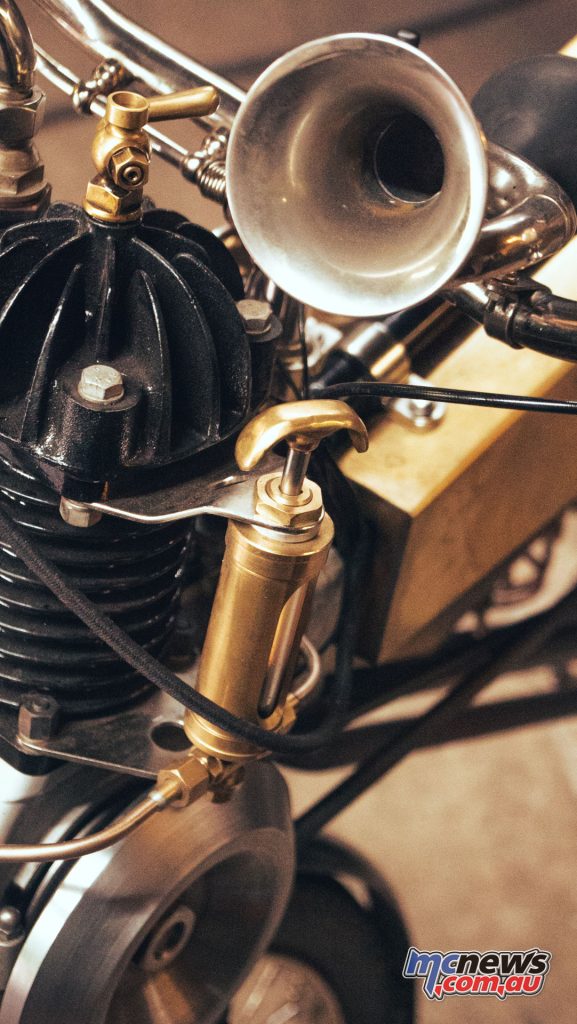

It was very clear from the outset that the mechanics, engineering and ergonomics of the original Royal Enfield motor-bicycle was worlds apart from the motorcycles of today. One of the most obvious differences was in the mounting position of the 1 3/4 hp engine, which was clamped onto the steering head above the front wheel, which in turn drove the rear wheel via a long crossed-over rawhide belt.

Gobiet hoped that powering the rear wheel would reduce the side-slip commonly associated with front wheel driven Werner motor-bicycles. Unlike most other engines, the Royal Enfield’ crankcase was horizontally split. This avoided the disastrous consequences of oil dripping onto the front wheel from leaky vertically split crankcases.

A Longuemare spray carburettor was situated on the side of the petrol tank some distance lower than the level of the engine’s cylinder head, a secondary feed was taken off the exhaust and passed around the carburettor mixing chamber to warm the fuel and prevent icing.

Lubrication was total loss, the rider squirting a charge of oil into the crankcase via a hand oil pump located on the left side of the cylinder. This would burn off after 10 to 15 miles at which point another shot of lubricant was required. The cylinder head housed a mechanical exhaust valve and an automatic inlet valve. The inlet valve was held closed by a weak spring and opened by vacuum.

As the piston travelled down the cylinder, the inlet valve was sucked open allowing a charge of air-fuel mixture in. A contact breaker assembly on the timing side axle triggered a trembler coil, which sent a rapid succession of pulses to the spark plug. This resulted in a good burn despite running at very low revs.

Starting the machine required pedal power, and then once the engine fired, the carburettor was opened from its tickover to full-on position by a hand lever located on the right side of the petrol tank. There was also no throttle – speed was modulated by the use of a valve lifter which was opened by a handlebar lever.

To slow, the rider applied the valve-lifter. This opened the exhaust valve and as there was now no vacuum in the cylinder, the automatic inlet valve stayed shut and no air-fuel mixture entered the cylinder head. As soon as the rider closed the exhaust valve, the inlet valve opened and the engine fired. Hence, an observer might think the engine was intermittently cutting out when, instead, the rider was simply controlling his speed.

The front wheel had a band brake that was applied by a Bowden lever and cable arrangement operated by the rider’s left hand. The rear wheel also had a band brake but this was operated by back pedaling. The saddle was a leather Lycette La Grande and the 26” wheels were shod with Clipper 2 x 2” tyres. It cost exactly £50 which is the equivalent of £4000 / 4,745 Euros in today’s money.

With all this background information gathered it was then a case of the ‘Project Origin’ team combining new-world technologies with old-world skills and practices to start the full reconstruction of a faithful working replica from the ground up. As the build took form it was quickly apparent as to the level of craftsmanship and expertise that were required to manufacture certain component parts of the motor-bicycle.

One of the most complex and intricate elements lay in the construction of the folded brass tank, which was masterfully handcrafted from a single sheet of brass – folded, shaped, hammered and soldered using age-old tools and techniques now almost forgotten to modern manufacturing.

The tubular frame of the motor-bicycle was expertly brass-braised by the team at Harris Performance as well as a number of hand machined brass levers and switches. The engine was completely built from scratch, and with no reference blueprints or technical diagrams to refer to the team was required to intricately study the few photographs and illustrations available from 1901 in order to develop CAD designs for each component part which were then either individually hand-cast or machined from solid.

In addition, the team hand turned the wooden handles, manufactured the front and back band brakes, and had the carburettor built from scratch. The turn of the century period original parts that were sourced; the paraffin lamp, the horn, the leather saddle, the wheels – were all reconditioned and nickel plated to give the impression that the finished ‘Project Origin’ motor-bicycle had just been unveiled to the public for the very first time at the 1901 Stanley Cycle Show, as would have been the case 120 years ago.