Barry Briggs

New Zealand great Barry Briggs may be a four-time FIM Speedway world champion, but his trophy haul only tells a fraction of his incredible story.

On the bike, he was one of the all-time greats. Off the bike, he was a businessman, an inventor, an adventurer and often all of those things at the same time.

FIMSpeedway.com celebrates the sport’s 100th anniversary this year and they caught up with him as part of their Stars of the Century series and sent this feature interview across to us to share.

Firstly Barry, how did your speedway journey start?

“It all started in Christchurch (on the east coast of New Zealand’s South Island). They put a new practice track in there and I was probably about 12 or 13. I was always into motorbikes. My cousin had a motorcycle, I had to clean it to earn my rides – I’m probably still behind with my cleans!

“There was also a small practice track, I knew most of the fellas, but I had no money. I was the bloke they shouted at ‘hey, I need fuel’ or ‘hey, the tyre’s flat.’ I used to do all those jobs and I got 10 free laps for that at the end of the practice.

“All the riders went down the straights flat-out and around the corners slowly. I went slowly down the straights and as fast as possible around the corners. They thought I was an idiot, but that’s how it started.

“Then the local soft drink manufacturer sponsored me with a bike, and I made my own leathers on my mother’s sewing machine. I broke what seemed like a million needles!

“In my first meeting I rode, I fell off after the race was over. I found that there was a design fault in my leathers – I didn’t put enough padding in the knees. I quite badly hurt my right knee and I was in hospital for a couple of days.

“Mum didn’t want me to ride. I was thinking of going to England. She was really against it, but I talked her out of that. After that crash when I was in hospital, she came up to visit me and brought a speedway magazine, so things weren’t quite so bad, but she never watched me race again, sadly.”

You mentioned that money was tight in your younger days.

What jobs did you do before you headed to England?

“When I was a kid, I got a delivery job at the local grocer’s shop, and I learnt about finance in one foul lesson. As I was earning, I bought a new bicycle on hire purchase. It was stolen within one week, so I had to pay over one year for something I never had – tough lesson! Then I worked full-time at an advertising agency for around a year and a half.

“Three months before I was leaving for England, I got a job at the meat works. I started very early in the morning, about five o’clock, packing kidneys and all that stuff. The boss knew what I was doing it for, and really helped me to get the cash I needed. It got a bit tough on the boss because the other workers knew he was helping me and gave him some stick. But full marks, he stuck to his guns.”

What do you recall about making the move to England?

“I had to go by boat which took six weeks. I got to Sydney and the boat had a fire, which delayed us by two weeks getting to England and those two weeks drained my money. I had my first cash flow problem and I remember the Sydney YMCA coming to my rescue.

“I was a naïve kid. We stopped in India, where we went ashore. There were some really sad sights. There were kids with one leg and one eye or just disfigured in some sad way, mostly done so they would get more money when they were begging. I was dumbfounded and really felt sick.

“I just wanted to get back on the boat. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. You were unexposed to that kind of stuff. You didn’t really know what poverty was. It was a big learning curve.

“I was supposed to go to Aldershot when I came to England, but promoter Ronnie Greene sent me a message ‘will you come to Wimbledon?’ I definitely wasn’t another Ronnie Moore as a speedway rider. Aldershot was definitely my level. I was 17, I had my own special leathers, I had come halfway around the world to be a speedway rider, but I had no bike. How ridiculous!

“An American team raced in England and were based in Dublin, but they closed down a couple of years earlier. Their old bikes were owned by Ronnie Greene. The boys managed to prise one away for me. I have no idea what they promised Ronnie from me.

“I knew I had an old bike, but I never blamed my lack of success on bike trouble. I took the blame head-on and later in my career, I found it made me a better rider. I had a bike, I was a real speedway rider, but I knew nothing. I was in another world.”

One man who helped you with conquering the world was another New Zealand legend, two-time FIM Speedway world champion Ronnie Moore. How much of an impact did he have on your career?

“I was friends with Ronnie. We belonged to the same cycle speedway team in Christchurch, so I got to know him a little bit then. I didn’t know him very much, but Ronnie was a star turn in Christchurch. He used to go to school on a 3T Triumph motorcycle. All the girls chased him, and he was a hero. I thought ‘that’s not a bad deal.’

“When I got to England, he treated me like a brother. He went to England a couple of years before me and knew the ropes. Ronnie had been a hero to me since I was a school kid. He was unbelievable. He would get a maximum in most matches. I wasn’t in the team for quite a while, but when someone got hurt, I was a reserve and got their rides.

“Even if Ronnie got a maximum on the Monday night, he would still be down at the track the next morning at 7am. He certainly didn’t need practice. He did it just for me. Ronnie looked after me. I probably would have made it without Ronnie. But I think it would have taken me quite a bit longer.

“Later in life, it got very difficult. When I was behind Ronnie, I couldn’t give him a push and a shove. He was always my hero.”

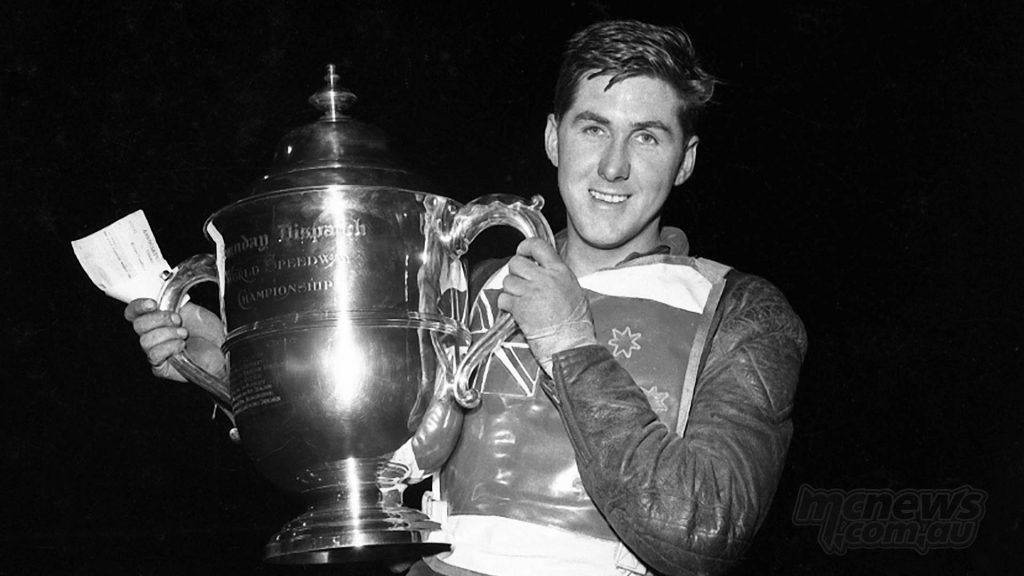

Your first FIM Speedway World Final win came at Wembley in 1957.

You won it after a run-off with Swedish legend Ove Fundin – the two of you tied on 14 points.

What do you remember about the run-off?

“Ove was tough; he was a much better starter than me. He made the start, and I caught him up. I got beside him on the third lap going down the back straight. Then, unbelievably, he hooked his left arm over my throttle arm.

“My brain was thinking, ‘Ove, you’re going to go for a whopper here,’ Now the pressure was on me. I had to stay right on the white line 100 percent because if I had entered the corner and drifted off the white line, I would have been excluded. I stayed right on the line. Ove ended up in a heap in the fence. Even Ove couldn’t turn the corner with his missing left arm. Whoopee, I was world champion!”

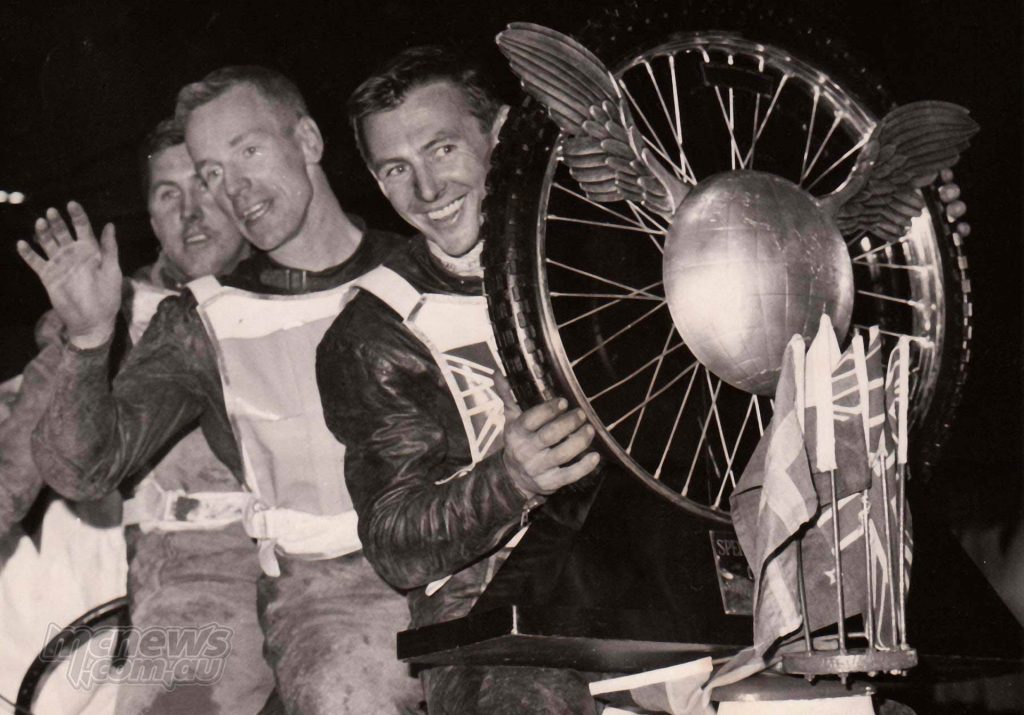

Incredibly, you won your other three FIM Speedway World Finals with 15-point maximums – at Wembley in 1958 and in Gothenburg in 1964 and 1966 …

“Some riders won their finals with 12 points. I could never do that. I would get 14 and finish second or something like that. I wasn’t the best rider there, but without being boastful, with Ove or Ivan Mauger’s mechanic, I figure that probably I could have won eight finals.

“I came up with the theory that you go into a World Final cold. One time I went to Swindon to warm everything up and blew up my best bike. On the way back to Wembley, I ran into the crowd leaving the Newbury Races.

“The traffic was bad, and I got to Wembley at about 7.30pm. I saw a copper on the side of the road and shouted ‘hey, can you get me through?’ I wouldn’t have made it without him. Everyone had a laugh when he told his story on my ’This is your Life’ television show.

“There was another one in 1962 when my engine wasn’t going, and I borrowed one from a German rider mate, Josef Hofmeister.

“In my first race, I dug a big hole with wheelspin, and only got a hard-earned third place. Then I won everything and finished second in the end. Afterwards I found that Hoffy’s engine was at a ridiculous 18 to one compression. A normal compression is 13 to one. With the higher compression, you had to be gentle on the throttle at the starts. It was my fault for not testing it.”

You nearly didn’t race in the 1959 FIM Speedway World Final. Why was that?

“My promoter Ronnie Greene and the Speedway Control Board bought in a rule that the maximum he could pay me for my New Zealand return fare was £250. The cheapest boat fare I could get was £280, so I said, ‘it’s £280 – final offer.’ Their reply was ‘£250 – that’s the maximum.’ My answer was ‘you can stick your speedway, I’m finished.’

“My wife Junie and I flew back to New Zealand at a cost of £700, where I didn’t ride. There was a World Final coming up with no world champion. I was a stone and a half overweight and had no bike. I only came back to sell my record shop. I felt that the English part of my life was finished.

“I did come back. It cost someone around £1,000 to bring me back to Wembley, where I finished third. Thanks to the SCB and Ronnie G for getting me back to the UK, but unfortunately not as the No.1 prepared speedway rider!

“This was stupidity at its best. It cost them £1,000 and I was also stupid for finishing as a speedway rider for a measly £30 pounds, especially as I won the previous two World Finals. At that time, I was above all of the riders, and nobody could realistically beat me.”

You lost a finger at the 1972 World Final – your last World Final. What happened there?

“I decided I wanted to be world champion one more time before retiring. My form had slipped a little and I decided that my concentration was being broken due to my role as an agent for Jawa.

“When I was at the track to perform, I would be going on to the track to try and beat Ivan Mauger, Ole Olsen or any top rider, and then a rider’s mechanic would come to tell me that my shop manager had only sent them one set of valve springs instead of two – exactly what you don’t need to be a winner. So, for three months, it was ‘I’m Barry the speedway rider, please leave me alone.’

“In my first ride at the 1972 Wembley Final, I was against Ivan. We had done this same procedure countless times over the years against each other. I would go straight to the tapes when the marshal dropped his arms.

“I was on gate two with Ivan on gate three. I went in quickly, chose where I was going to start and quickly pulled back. Ivan kept digging his place to start but kept looking at me. He didn’t know what to do because I wouldn’t go to the start until he did. I beat Ivan by 20 lengths.

“I was on great form and confident. I knew Bernt Persson was in my second race. I made the start and going into the first corner, I should have stuck Persson over the grass.

“Stupidly I gave him room and suffered the consequences. Photos show Persson going straight on instead of following the white line. I kind of blame him, but not completely. It was also me. I am supposed to control that situation. But stupidly I gave him something that he certainly in my estimation didn’t deserve.

“Persson knocked me off and a Russian ran me over. When Persson came under me, my hand went up his back wheel. My finger was pulled off. It was still on there, but it was hanging. Ivan ran up and told me to tape it up for the rest of the meeting. ‘No good, Sprouts. It’s knackered,’ I said.

“They took me to Mount Vernon Hospital. That’s where all the Battle of Britain pilots were looked after. They told me that I could keep the finger, but it would probably be stiff. They said it was better to have it off.”

That’s clearly not your best Wembley moment, but the place must still hold special memories for you …

“I think I rode at Wembley about 50 times. A Wembley rider like Freddie Williams would have done more meetings there. But no sportsman or any kind of entertainer has done what I did at Wembley – that’s what I’m told. I raced for 21 consecutive years at Wembley, which I am told is a record. I don’t know. No matter how good a footballer was, they couldn’t have done that. They aren’t going to play there every year.”

You received an MBE for services to sport from the British royal family and finished second in the prestigious BBC Sports Personality of the Year vote in 1964 and again in 1966 – the year England won the FIFA World Cup at Wembley. Was that last one unexpected?

“We were a popular sport. In those days, we were virtually filling Wembley for every World Final. We did it all the time with speedway. They would get 50,000 for league matches.

“Wembley at the time had the world’s largest supporters’ club with 60,000-odd members. Five to 10 buses went to every Wembley away meeting. Speedway was big-time. Today people have no idea.

“How did I get second place in BBC Sports Personality of the Year? Well, in football, a Tottenham fan wouldn’t vote for an Arsenal player or vice versa. But speedway people will vote for an individual like they did for me.

“I was thinking, ‘the last thing I want is to win that!’ It would have been ridiculous. We had the FIFA World Cup in England. It was bad enough me being second. I was second to England captain Bobby Moore and ahead of Geoff Hurst, who scored the hat-trick. It just shows that speedway people would vote for me.”

Bikes with laydown engines – motors that sit horizontally in the frame – have been commonplace since Speedway GP launched in 1995.

You raced with upright engines throughout your career, but you created a very early laydown. How did that go?

“I was one of only riders to make a laydown speedway bike. It nearly killed me. I never could get the carburettor sorted.

“After finishing in second place in a qualifying meeting the day before at Invercargill, New Zealand, I simply was not winning the starts – the very reason why I made my laydown.

“During testing the day after, I was only going from the start to the first corner. I wasn’t even wearing a steel shoe and we precisely timed every start to the first corner. I felt that the laydown’s big advantage was its low centre of gravity, giving you more controllable grip.

“I had finished for the day and decided to do one last run. All of sudden the throttle jammed flat-out and didn’t shut off. I did what I’d done 100 times in my speedway life – I just threw the bike away. Then the spinning back wheel should take the bike away from you by ten yards or so.

“I can’t remember why, but I was wearing this new cut-out string on my wrist. The bike went until the string pulled out, stopping the spark. But when the spark stops, the bike just falls on the top of the fallen rider – me.

“Lucky an Aussie surgeon was passing through Invercargill and saved me. But it was tough on my wife Junie, who along with a mate had to try and keep heat in my body as I lay there shaking badly.

“American rider Ernie Roccio had a laydown when he was at Wimbledon. It was a JAP one. They did the carburettor in a funny way and he never really got it going right. I don’t remember him racing it in Britain. He said he had it going alright in America, but Britain was a different thing.

“I looked at the concept and thought ‘that’s a good idea.’ I was in New Zealand, staying at my mate Tommy’s place. I was in my bedroom going to sleep and I grabbed a book off the shelf. It was called ‘Tuning for Speed.’

“The last Norton was a laydown engine. I also remembered the Italian Aermacchi road racer bike, which was much quicker through the corners than the conventional uprights. I looked at it and thought ‘that could be good for speedway.’

“I built the thing. To me, it was brilliant. But the only reason I built it was to make the starts. I rode the bike in New Zealand and that’s when I got hurt.

“I only had to do four meetings to get to the World Final and this bike, to me, was going to fly out of the starts. I would have beaten them all no problem at 55.

“I feel that I would have definitely been world champion if I had been Polish and lived right next to a track. When something didn’t work, you could just wheel it back into the workshop, fix it and try again. Instead in England, you had to go all the way to Weymouth for testing, which was a full-day task, only to find in five minutes something was wrong, or you simply ran out of time.

“Laydowns are great because the weight is low. To me, with the right carburettor, it would have been lethal against all the uprights.

“Through the Speedway Star you see crash photos you would have never seen from the JAPs and two-valve Jawas. The laydown bikes when they get unexpected grip just take off in whatever direction they are heading.

“Looking back, the authorities should have banned my laydown. To me, they just made speedway more dangerous. All they really did was double the costs of bikes. A £30 carburettor is now over £1,000 I’m told, but boy I would have loved that £1,000 carb just for four meetings to get to another World Final.”

Your youngest son Tony followed you on to the track. He suffered serious injuries and was paralysed while racing for Reading at Coventry in 1981.

Obviously, this played a big part in him designing his lifesaving ’No Pain Barrier’ air fences.

What was going through your mind at the time of his crash?

“When he crashed, I was in the pits, and I was thinking ‘what’s happening? Nobody is touching him or moving him.’ I was really nervous about it. Then I realised they thought it was something serious. It was Dr Peter Kenyon, who saved him.

“He was transferred to a specialist spinal unit in Oswestry, with police closing the motorway to take him down there. The hospital in Oswestry was fantastic.

“He was paralysed for two to three months. He was only moving his eyes. I couldn’t handle it. I had to get out of there at times. My wife Junie sat there every day, rubbing his hands. Then one day, Tony’s little finger moved. It all started from there. Then he had to learn to walk again.

“This shattering experience got Tony focused on designing an air fence for speedway. Tony was also involved when we did a Hall of Fame display at Donington Park Museum, and he helped me put together our display ‘Lest we Forget’, a list naming over 120 riders that had given their lives to our sport. That was sad, especially as I knew over 50 percent of the boys.

“He went off motorbikes, but now he is the same as me. We ride all the time. I ride many times in the forests in Poland. Tony comes to California at Christmas, and we get in plenty of riding.

“The crash was a tough one for him, his mum and me as well. I was the bloke who set the example for him, and he was such a good rider. Nobody realised quite how good.

“But the amount of action Tony’s air fences have experienced over the years is unbelievable. I wonder how many riders have been saved from serious injury, or of course even worse.”

You came up with, designed and developed a key safety feature for speedway – the dirt deflector. Who has benefitted most from this?

“Firstly, it was to protect the riders from the six-inch wide jet of dirt that previously flew off the back wheel at an amazing velocity into the following rider’s face. If it’s adjusted to the FIM rule book, the stream of dirt only hits the riders below their kneecaps, making things unbelievably so much safer.

“The gain to promoters has been amazing. A minimum of at least 80 percent of meetings that would normally have been cancelled now take place after the introduction of the deflector simply because the riders can now see. It showed its importance in this year’s first Speedway GP in Croatia, which would have definitely been cancelled without the use of deflectors.

“When I started the designing process of a deflector, my full concern was riders’ safety – for them to be able to see and ride on wet and muddy tracks.

“My first thoughts looking back were two-fold, first the riders and then the fans, especially people like the two busloads of supporters from Scotland that had spent their hard-earned cash to come to Swindon and watch one of my Golden Greats meetings, which was rained off while the sun was shining!

“To me, the promoters were the biggest winners money-wise, saving them thousands of pounds over the years by not having to cancel meetings due to wet tracks.”

You famously gave Steve McQueen a few lessons on how to slide a speedway bike. How did you meet him and how did he get on?

“I bought my house in California from film director Bruce Brown. Bruce made a big hit motorcycle movie called On Any Sunday. McQueen put the money in and starred in it. Bruce became mates with McQueen.

“I took Bruce out to a small speedway track for him to try and ride a speedway bike. The track was part of a local motocross park. Bruce was getting ready for his ride when two motocrossers turned up. Low and behold, it was Steve Mc and his mate Roger DeCoster, who was a world-champion motocrosser. I already knew Roger, so we finished up with three new potential speedway riders.

“I was dressed in a pair of shorts and trainers. I didn’t even have a steel boot on. Looking back, I hope they didn’t think I was showboating, as it’s like falling off a log for me. It’s like walking. It looks easy, but it’s not unless you know exactly what you are doing. It certainly takes time to learn to do it.

“Bruce, McQueen and DeCoster … all three crashed. Steve and Bruce took it well, but Roger was upset. Steve looked up to Roger as God on a motorcycle, but Roger got a shock. Speedway is tough and a completely different kettle of fish to doing amazing things on his motocross bike.

“All three were good motorcyclists and could slide their motocross bikes to beat the band. I’m sure with a little more time, they all would have quickly become much better. But we only did it for a day.”

You also got to know legendary ex-Formula 1 boss Bernie Ecclestone. How did the two of you meet and is he a speedway fan?

“Bernie is an old speedway supporter. He used to go to Wembley for the Speedway World Finals on his Ariel Square Four bike. I was in his offices with his TV man Alex Whittaker, discussing a cartoon film of the world-famous English dog Fred Bassett, which I was getting drawn in Russia for a half-hour cartoon film through a Finish rider mate, Ila Teromaa. But that’s another story!

“Bernie found out that I was with Alex, and he came to visit me. Alex said Bernie had never been into his office, but he came down and spent a couple of hours quizzing me.

“I like Bernie. At one stage, he asked me about putting speedway tracks in at the Formula 1 races – so that we could have speedway the night before the F1 as an added attraction. I can’t remember what stopped it.”

Away from the sport, you had a number of business ventures both during and after your racing career …

“When I was at Wimbledon, I opened a record shop in Garratt Lane. Rock star Tommy Steele was going to open it, but due to commitments, his brother Colin Hicks, also a rock and roller, opened it for me.

“I also started a driving school. I ran that for nine months. I was there to make money and I’d tell my customers the truth, ‘hey, you only need a few lessons to brighten your driving skills up.’ Ridiculously, these were mostly the ones that failed. The ones who were, in my opinion, not so good, passed. I wasn’t built to stand that.

“At the time, all driving schools had their name plates on the front and back bumpers. One thing I did for the driving-school world was having the Barry Briggs Driving School name plate double-sided and fitted across the roof. Now everyone does it. It was smart, but I made no money from that little gem!

“I’m an inventor of sorts – always looking to improve things around me. I made a golf putter. I sent my new putter to the R&A, and they said, ‘this is wrong and that’s wrong.’ I told them, ‘It’s made exactly to your rulebook.’ They replied, ‘you can only use that as a rough guide.’

“I did it again and it passed. Every month, all the manufacturers get a circular letter from the R&A. I may be a one-man band, but I still get one, even though I have only made one putter.

“Normally you swing a putter across your body. Mine you simply swung beside your body, just like bowling a ball forward underarm. I didn’t try to sell it. It was just the thrill of the chase.

“Two years ago, the USPGA asked a top US top golfer not to produce the very same type of putter because it could cause chaos – just like the long putter did, so I didn’t feel such an idiot then!”

Diamond mining in Liberia was one of your wilder adventures. How did that come about?

“While Tony was in hospital in Oswestry, former speedway rider Ray Thackwell came to visit. He was into a gold mine in Wales. It was the Royal Clogau St David’s gold mine. It supplied all the royal gold for wedding rings and crowns. He owed me money and I took part of the shares. Then I was on the board.

“As I was in that field, I met people in Australia who had gold mines all over the world. We went to Liberia. Tony was getting over his broken neck and the laydown experiment had cut me open as well. I was also having a few problems. We healed because we were close together.

“The plan was to locate diamonds and then sell the site to a company with the resources to extract them.

“We got a lot of diamonds. They were hard to get to. The ground consists of different layers of material; one of them being where the diamonds are. Normally old rivers are best.

“The machines to get down to them cost a load of money. You need bulldozers and heavy equipment. I figured out we could do it with water. I went down to St Austell to see the pottery people. They do that in the clay pits. I found a speedway fan who really helped to sort me out.

“We did it with high pressure water from the adjoining River Loffa. We washed off the top layers of dirt and pumped it out of the way. When you get to the layer of diamondiferous materials, you have to be very careful; that’s where your payoff is.

“We were living in the jungle and had made our own mud hut. We were there for four years. We found a load of diamonds and had all the paperwork done with the Liberian Government to go on the stock market in England with our mine. But our luck went sour when the world’s stock market went up the wall on Black Monday in 1987.

“Our mine was valued at $43 million, but this market crash just finished our activities in Liberia right there and then. The whole world went upside down and it was virtually worthless. We just washed our hands and moved on to our next adventure. There’s no use crying over spilled milk!”

You have never been afraid of taking chances on or off the track, but what was going through your mind when you decided to drive your 1977 Rookie of the Year, 200-mph Indy car at the famous Indianapolis track in the States at the age of 81?

“Your own brain at times is the most negative part of your body, screaming, ‘you’re going to die! You’re going to die.’ My answer is ‘no! I’m going to learn this’, so I just drove on.

“I was determined to learn how to do this. I got up to a 150-mph lap. My car qualified in 1977 with a 185-mph lap. I think with another 50 laps, I would have reached the 185-mph qualifying time. I am told that I’m the fastest-ever 81-year-old to have done a 150-mph lap at Indy. Maybe I’m the only 81-year-old with the brains – or lack of – to drive at Indianapolis at that age.

“I had a rough idea what I was trying to achieve, and quickly understood that you don’t wrestle with the steering – a sure way to get into massive trouble. It’s just like trying to guide a missile, you have to go softly, softly, guiding it away from any potentially dangerous objects, fences etc.”

Even at 88 you still ride motorbikes all over the world.

Even at 88 you still ride motorbikes all over the world.

How have you maintained your sense of adventure and what’s the secret to keeping yourself so active?

“If you want to do something, there is always a way. I just think, ‘I need to do that, so I have to do this.’ And I do it.

“I think age catches up on you gradually. You have to be able to bear a little bit of pain now and then. I have trouble with my leg. My doctor tells me ‘Barry, you don’t walk enough or drink enough water.’ He’s right on both counts. I’ve tried harder over the last couple of years – a big improvement.

“It’s all about your want. Some people say ‘oh, I am getting old’ and accept what they are given. You can’t do that. You might have to do something more to do what you want to do.

“I still do the same stuff. I don’t know how many miles I rode in the Lake District recently over five days, I did a lot of riding over and around the passes and mountains. I was probably doing four hours a day. I normally do around a three-hour ride twice a week in California.

“I normally try to ride off-road, in the mountains with narrow trails, rocks and stuff like that. You must stand up over the rough dirt to ride well. You can be sitting down and then you get a big change in terrain, so you have to stand to be in full control when you’re at speed.

“The full movement is like going to the gym – with a normal seat setup I can only last around 20 minutes. My legs have real trouble doing the full movement repeatedly, so I made a pillion seat fitted on to the back of the normal seat, which means while sitting on the pillion, I am only a half an inch from standing. On that system, I can easily ride for three hours.

“I have made the bike to suit my body. I mount my bike, held upright by the side prop stand. Then it’s just like a cowboy, when he puts his foot into the stirrup and swings up on to his horse. The only difference is it’s up on the footrest instead of the stirrup to swing over on to my bike. The advancing years have made it harder to lift my leg high enough.

“Everything is designed around my body capabilities. My hand with the missing finger has no real strength in it, so I have made something flat for the hand to sit on. I’ve taken flat cycle grips and grafted them on to my originals, so I don’t have to grip as strongly.

“I find at times that I have to think completely differently because I want to ride my bike with a worn body. At times I have to think out of the box to find a way of achieving this.”