Greg Hancock talks his Speedway career

Paul Burbridge talks shop with Speedway GP icon Greg Hancock to reflect on his career. And that has been some career; four Speedway GP titles, 218 Speedway GP appearances, 455 race wins and 2655 championship points collected.

Firstly Greg, how did your speedway journey start?

“My dad Bill started to take my sister Carrie, brother Dave and I when I was around four or five years old. He was newly divorced from my mum and living alone, and eventually he became friends with (American rider) Josh Larsen’s dad Charlie, who was also newly divorced. They ended up living on Balboa Island – upstairs and downstairs from each other.

“Long story short – Charlie got my dad into speedway because he was watching it. He got my dad really hooked on the sport. Charlie also became friends with and started to help (legendary American rider) Bobby Schwartz at that time. He introduced my dad to Bobby too. They started to support Bobby with some sponsorship and through all that, Bobby got my brother interested in speedway.

“From the first moment we saw junior speedway live, I was running around underneath the grandstands collecting tear-offs thrown by the riders or all of the beer cups. When I saw the junior speedway guys, like Kelly Moran and eventually Dennis Sigalos and Lance King, these guys became my new heroes.

“I just remember from that point on that I never stopped tugging on my dad’s back pocket to try speedway for myself. It was the biggest addiction I got into from a very early age, and it never left. It still hasn’t.”

You gained a lot of heroes as you followed the sport in California, including top American riders like Bruce Penhall, Dennis Sigalos, Bobby Schwartz and John Cook, and it sounds like a number of them helped you become the rider you became …

“From day one, my dad was associated with a lot of the greatest riders. Having Bruce Penhall, Dennis Sigalos and Bobby Schwartz around was great, and they became part of our extended family.

“It was a no-brainer. I was around these guys from the word go and I had the red carpet rolled out in front of me. All I had to do was walk it and respect it, and just take in all this great knowledge getting thrown at me, which I did.

“I never took advantage of it in the wrong way. I took advantage of it in a positive way and learned from these guys.

“Bruce quickly became one of my heroes because of his rapid success. But he always had time to come down to your level and talk to you as a human being. He was really easy-going.

“Bruce and his mechanic Spike are the ones who nicknamed me ‘Grin’ back in the day. They used to give me advice constantly and they’d say, ‘We don’t know if he’s really getting what we are saying because all he does is grin.’ All I did was smile and take it all in, but they obviously wanted some sort of a response, and I didn’t always give them that, so they were thinking, ‘What the heck is up with this Grin guy?!’ Bruce’s success played a major role in my career.

“I turned to Bobby for so many things over so many years. I had Bobby on a different level to Bruce. Bobby didn’t beat around the bush. He told you straight. Bruce would say, ‘You could have maybe done it like this.’ Bobby would say, ‘You don’t do it like that. You do it like this.’

“I had the best of all words. All they were trying to do is help me find my way forward in different ways with the different upbringings they had. I had all this free information and all I had to do was absorb it. In a nutshell, that’s what I did.

“John Cook became my next big brother. He is the one who really started to emphasise things about Europe and explain things to me.”

What were your first experiences of speedway in Europe?

“I went to Europe in 1985 – I went to watch the World Final at Bradford. I stayed with John for most of the time. I also stayed with Bobby for a couple of days, but most of the time with John.

“John really painted the picture of British speedway for me. I got to work in the pits with him regularly, cleaned his bikes and I just really lived it. That was the key moment of me saying, ‘That’s what I want to do.’ I was 15 years old, but I was thinking, ‘This is me. As soon as I get the opportunity, I am coming.’

“That’s what I did and in 1989, I got the call. I was quick to jump at the offer. I had the red-carpet treatment. Lance King offered me a place to stay. Little did I know at that point he was in his final year of racing in Europe, but I had everything to gain – his workshop and his knowledge. He showed me where to go, what to do and what not to do.

“He was hard on me, but we also had a lot of fun together at the same time. He was a bachelor, and I was a young punk kid. When I did something wrong, he’d say, ‘Dude, you just don’t do that! If you want to do it right, you do it like this. You work hard and you play later.’

“He was amazing. He would wake me up if I was sleeping too late and play his electric guitar super loud downstairs, telling me, ‘Get up!’ We laugh about it, and it was all meant in good nature.

“He installed the software for me from the very beginning. I literally ran my career, all my pre-season stuff, how I set up my workshop and everything I did based on what I learned in year one.

“All I had to do was make the updates to the software that he installed. That’s what I tell everybody, and I tell Lance the same. I still have in my workshop some of the equipment Lance gave me to set up a workshop from the very beginning. I still use it in some cases. It’s a piece of my history that reminds me of the hard work, effort and people who taught me what I know.”

You became very close to three-time FIM Speedway world champion Erik Gundersen and you were racing in the 1989 FIM Speedway World Team Cup Final in Bradford, where he suffered the crash with Lance King, Sweden’s Jimmy Nilsen and England’s Simon Cross that ended his great career. What do you recall about that day?

“Erik had his accident in the first year I was in Britain riding for Cradley. I was there with the American boys and Lance was involved in that accident. All four riders went to the hospital that day.

“It was a scary moment and Lance still lives with so many negative feelings that he was involved. They all tangled going into that corner and he was one of the first guys to touch Erik as they all met in the middle of the corner.

“I probably shouldn’t say it, but Lance puts a lot of blame on himself and psychologically, it really affected him. It still affects him. Erik was one of his heroes too. There are a lot of emotions among all these guys – from Simon Cross and Jimmy Nilsen too. They were all involved in that day which ended Erik’s career and changed everybody’s lives forever.

“I didn’t understand how serious the injury was until after the racing was over that day. We went to the hospital to pick up Lance and that’s when we got the news how bad Erik was. It was a career experience – one of those days that feels like it was yesterday. I was one of the reserve riders and all four reserve riders came out for the restart of that heat. I finished second in the re-run, and I didn’t score a point after that.”

You ended up living with Erik in the years that followed. How much support did he give you in those crucial early days of your career?

“Billy Hamill and I had the opportunity to go and live with Erik. We took that opportunity, and it was great. I got to live with my hero.

“He took these two young punks into his house. It was pretty crazy when I look back on it. What a gamble it was for him and his wife Helle – probably more for Helle than anyone. But it turned out to be one of the greatest experiences of my life, living with a hero and learning how he did things.

“I thought after living with Lance at the beginning, this would be even harder. Lance said, ‘Dude, you are going to eat, sleep and drink speedway. It will be like the military living with Erik.’

“It was like the military, but it was the most fun military I have ever seen. Erik never made anything stressful. He made everything fun. He said, ‘You have to do your work, but if you don’t do your work, it’s going to affect your performance. You get your stuff done and then we’ll have a party later.’

“It was the greatest thing ever, having access to his house, his hospitality, his workshop, his mechanic, his equipment … it was any kid’s dream. Who gets that? Who gets that even today? And this is what I try to give back to people like Maciej Janowski or Luke Becker as we come to the present day.”

Is this where you struck up your friendship with longtime race partner Billy Hamill, or were you friends before you moved to the UK?

“Billy and I were friends in California, but we weren’t super close friends. I dated a girl that lived in the same area that he did, so I spent a lot of time with him here and there.

“We weren’t the closest of buddies and we didn’t really become friends until we lived with Erik. That’s when we really got to know each other a little bit better. Living together, working together, travelling together, racing together, going home together and starting it all again the following day helped, and we had Erik and Helle there as our overseas parents, guardians or heroes – whatever you want to call them. As father and mother figures, they were just the best. They made sure we kept a good camaraderie.

“We had this natural thing that if he scored 10 points, I wanted to score 11. That was the natural carrot for both of us. If we were both pushing each other all the time, we were both scoring better and doing amazing things for our teams.”

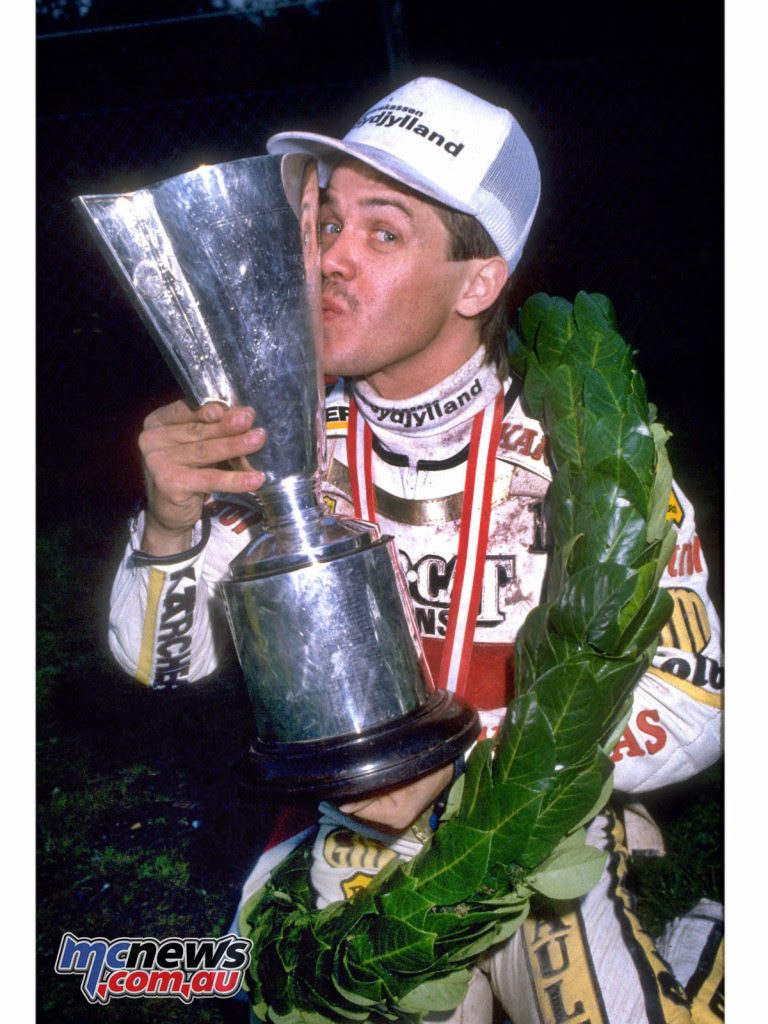

Billy became Speedway GP world champion in 1996. Did that inspire you to even the scores when you won your first in 1997?

“Billy got there first for everything in our careers. He got the first call-up to go to Cradley before me and he turned it down, so then I got the call, and I went.

“I went to Britain before he did, but he was getting all these opportunities before I was – opportunities that he was creating for himself; I am not saying they were given to him. He was creating opportunities by being a good, strong, solid and aggressive rider. I was the more easy-going guy, trying to find my way and thinking, ‘I’ll figure it out. I don’t want to hurt myself.’

“I think that was the biggest motivation for me to step out of the box a little bit and be a little hungrier. Watching him win the world title in the year we started our Exide programme in 1996, I was excited as hell because I finished third that year. I was happy for him, but at the same time I just wanted that to be me.

“For sure there was a rivalry. I was stoked for him because we both worked really hard and put in so much time and effort to develop this new Team Exide programme we were doing. It was absolutely amazing. But him winning made me even hungrier to take it the following year.

“Then 1997 was an amazing year. Every race just seemed to come to me. When you are on, you are really, really on. I just remember I had done a lot of work that year. My tuner Eddie Bull had done some extremely exciting work with an F1 racing team and developed some special cams.

“He made changes to the valve train of the engine and that was the first time I had something special just for me. We invested a lot of money into the programme, and it paid off. I was so fast that year and I had engines that were so nice to ride and so easy. They were really elastic – just so much fun. Only I had them in the beginning, which was great. I will never forget those times.”

Tell us more about Team Exide. Rider teams are rare in the history of Speedway GP. You and Billy were the first and still the most successful. How did it all start?

“I had received some sponsorship with Exide Batteries for one or two years already from a guy by the name of Tony Summers. Tony was a good dude and I met him through my Cradley connections.

“Billy and I were travelling home from the airport in 1995 and we started talking about how we should run a team. In the time it took to go from Heathrow back to our base in Tamworth, we had written a whole plan of how we were going to do it, how we were going to present it to our sponsors and what we were going to do with our race suits.

“We were going to start a team. I would go to Exide first, Billy was going to go to some of his sponsors and within weeks, we had this in the process. Tony loved the concept. He became a key partner for us in putting the whole thing together. He drew some interest from Exide in the UK, France, Spain, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Czech Republic and Poland.

“He got all these nations to chip in a portion of the budget for us and we created Team Exide. Whichever country we were in, Tony was there, and he was bringing customers from each regional distribution area. We had five to 10 to 50 guests coming to every GP and we were Team Exide.

“Tony also educated Billy and I so much on marketing, how to promote ourselves, how to talk to sponsors and how to sit at the dinner table. There were so many things we learned as young pups that he taught us. I learned a lot motivationally and I still use a couple of key tools he gave me today. They were big keys to my success.

“We were a team – we were identical. Our bikes, suits, mechanics and vans looked the same and we pitted together. We were ahead of our time in a sense.

“Speedway wasn’t quite ready for it and sadly the Team Exide programme only lasted two solid years and there was a much more minimal one in the third year. We really worked hard to try and keep it going and Tony did too. But the company couldn’t continue.”

One huge change for Speedway GP came in 1998 when the knockout format was introduced, which saw riders eliminated from an SGP if they finished third or fourth in two straight races. Is it fair to say you were not a fan of this?

“That started the very next year after I won the world title. In 1998, the first Grand Prix was in Prague. I went there, they ran the qualifying heats first and then we jumped into the main meeting. I was in the top eight, so I started in the main part of the meeting.

“I did two heats – two bad heats – and I was done. I just remember thinking, ‘What the hell?! What just hit me in the back of the head?’

“It was crazy. I can complain all day long, but it was the same for everybody. I think I was just overwhelmed, and I lost that hunger after all the years of trying and trying and trying.

“I got there, and I was thinking, ‘What now?’ I wanted to win again, but how badly did I want to win again? Did I want to put in all that effort and deal with all the emotions and stress? It took me some time to really find my way again.”

How did you find your way again? It took you 14 years to win Speedway GP world title No.2 in 2011. Who or what made the difference?

“For a lot of years, I was right there and close. I swapped and changed engines. I went over to Jawa for a little while and then back to GM. I started changing frames. All you do in speedway is what most of the guys are doing. Everyone is using pretty much the same equipment and just swapping and changing things, trying to find a mix that works for them.

“After having special engines for myself which were eventually getting shared out to other riders, I realised I was just another number in the game.

“You have to take advantage of your time when you can, and it wasn’t until 2008 or 2009 that I met the people from Prodrive when I was riding at Reading one night. That’s when things changed.

“This guy called Lars Sexton introduced himself and said, ‘I am sorry to bother you. I work for Prodrive.’ I used to pass that place 150 times a year going to and from airports. Of course, I knew who they were, and I knew who Petter Solberg is and all the rally teams etc that they worked with like Subaru.

“They said, ‘We want to help you. How can we help you?’ I was thinking, ‘Is this another one of those guys who says he can help me? What can he do for me? They are car people. I am a bike guy.’

“We loaded the bike up one day and drove into Prodrive. They took us on a tour of the museum, and we started meeting the engineers. I met this guy called Mick Metcalfe, who was the drivetrain engineer. He was a massive Coventry supporter. He was probably as starstruck as I was being in that facility. When we unloaded the bike and rolled it through the workshop, everyone who was at their machines or workstation stopped and just came over to look at the bike.

“They were all motorcycle nuts working in a car world and every single one of them was so excited, checking this thing out and thinking, ‘What can we do?’ We ended up leaving the bike there for them to hang out with and get a feel for it. They took some drawings and did a load of analysis. They started building frames for me.

“To cut a long story short, after I wrote off a few bikes and banged my head quite a few times trying to test new things, with things breaking and chains snapping, by 2010, they had developed a frame and fork combination. I put it on the bike and the first time I rode, I thought ‘Whoa!’ I was overcome. It was amazing. They had developed a frame that worked for me, trying to help me correct some bad habits I had after all the years of riding small tracks in the States and turning too hard.

“They made a bike I could ride the way I ride, and the bike would do all the work. I said to my mechanics at that point, ‘I can win the World Championship on this.’ My chief mechanic Rafal Haj said, ‘What?!’ I told him again, ‘I can win on this. This is amazing.’

“I went out there at the next GP in Croatia – the first one staged there in 2010 – and I won the GP. Even my mechanic was thinking, ‘What the hell?!’ I told him, ‘Dude, this thing is the business. I have something nobody else has and I am going to live every last moment of it.’ That’s where it all turned – right there. Everything came in 2011, it was just bam, bam, bam and I was thinking, ‘Bring it on!’ I turned 41 years old, and I found my mojo.”

Was there ever a time before you found this winning formula that you considered hanging up your boots?

“Around 2009 going into 2010, I was ready to hang it up. I told my wife Jennie, ‘Maybe that’s it. Maybe my days are done. This isn’t meant to be.’ I was having a low period and was wondering, ‘What am I chasing here?’ Maybe the ship had set sail and I had to move on.

“Without physically slapping me in the face, she slapped me in the face with some verbal therapy. She said, ‘What are you talking about?! You have not reached the end of your career. You have only just started. Can you believe how much work you have been doing and how much you still dream about this? You have so much more to give, and you should keep giving.’ I owe a lot to her.

“I met Jennie in the late nineties, and we got married in 2004. I turned 40 in 2010 and most people start to think about retirement then. I never thought about retirement. I was just tired of people trying to talk to me about it.

“I was just thinking, ‘Gosh, I am 40. I’m getting old.’ But Jennie told me, ‘Can you stop acting like you’re 40! Forty is not old. Don’t think about it.’ I don’t know what it was. But maybe it was that therapy and that moment – she gave me an awakening.”

During the 2010s, you came up against a new generation of rivals, including Tai Woffinden, Chris Holder, Darcy Ward, Bartosz Zmarzlik and your protegee Maciej Janowski. Did the challenge of taking on these young guns excite you?

“It did – it really excited me. I was starting to feel it again and there were these youngsters like Chris, Darcy and Tai – there were a lot of them. I realised I had to stay close to these guys. I became friends with them all and they ended up keeping me young.

“I stayed with them, talked with them, hung out with them and travelled with them. Then I suddenly realised I wasn’t a 40-year-old anymore; I was just a teenage kid like they were, living the dream!

“I realised these guys were good, with the things they talk about and do on the bike. I couldn’t do it their way. I had an old-school style with the way I rode. But I knew I could take a piece of what they are doing and apply it to my programme, and that’s what I did.

“They were learning from me, but I was learning from them. It was a win, win. Chris was really good to me. He always shared really cool information. He and Darcy were always fun. They always talked up my racing and they always looked up to me. They always praised me, but they also knew we could talk rubbish, have a beer, have fun, disagree, agree to disagree and I developed a really good friendship with them.

“Chris and I both helped each other as much as we could for a lot of years – both psychologically and mechanically. When he got hurt in 2013 and I covered for him at Poole, we had a lot of good times. He helped me when I was going through a tough time as well and I tried to help him as well.

“It’s not just racing camaraderie. It was a friendship where you care about somebody. You know that if you get down to a full-blown race, the gloves come off and you go for it. But at the same time, he helped me in a time of need, and I tried to do the same. It’s just being a friend. I have a lot of respect for both Chris and Darcy, as well as Tai. I know Tai really well and I knew his dad Rob really well.

“I had to stay close to these guys because I needed to feed off them and pick up on what they were doing and see if I could make it better.”

You won 21 Speedway GPs in 11 different countries – three of them at the iconic Principality Stadium in Cardiff in 2004, 2011 and 2014. What was it that made the FIM British Speedway GP there so special?

“Cardiff has always been my home track. I loved going there. I had so many years of racing in the UK with so many different clubs. All those fans supported you, whether you were at Cradley, Stoke, Oxford, Coventry, Reading or Poole. I also guested for so many clubs.

“They didn’t forget that on the night of the Cardiff GP. Everyone was there and it felt there was a lot of red, white and blue – not just Union Jacks. It was also the American stars and stripes.

“If a British rider didn’t win, they were stoked that the American guy won anyway and they were still stoked if it was a Polish, Swedish or Danish guy. The fans there love speedway. They make noise, no matter who you are. Still to this day I get goosebumps because the fans were so good to me there.”

You stepped back from Speedway GP ahead of the 2019 season after your wife Jennie was diagnosed with breast cancer. Can you put into words what you and your family went through at that time?

“She actually got misdiagnosed in Sweden at the end of 2018 in November. She found a lump in her breast, and we ended up going into hospital. They did a check and a biopsy. They called her in for a second biopsy and said, ‘You should bring your husband with you.’ Then we knew something wasn’t good.

“We were very nervous. We left the kids with her parents and took a bus to Stockholm because we didn’t want to drive. We walked into the oncologist’s office, and he said, ‘We don’t need to do a second biopsy. We had a meeting with the higher-ups, and we don’t believe it’s cancer; it’s just a calcification build-up in your breast. But we will keep an eye on it for the next six months and see if anything changes. Until then, you can go off to the US and live your life.’

“We walked out of the hospital. It was across the street from Stockholm Stadium. We have a lot of memories of racing there. We walked over to a bar right across the street from the stadium and we ordered a bottle of champagne and drank it. We just lived that moment and cried. Then we got on the bus and went home.

“Everything was normal, and we went back to California. But within two months of getting back there, she said ‘This thing is still growing in my breast. I don’t like this. It feels like it is getting bigger.’

“It was a scary moment, so we went to see the doctor in the States. They did an ultrasound and immediately said ‘Listen, there are some good treatments out there.’ She lost it. That was it and we started the process.

“They told us, ‘Don’t be angry or frustrated that they missed it in Sweden. Perhaps they didn’t get a good piece of the tissue when they did the biopsy. We can see clearly here – without even doing a biopsy – that this is cancer.’

“She turned out to be stage two, so they still caught it relatively early. But she wasn’t stage one, where she probably was before. They had to start more or less immediate treatment. This happened in late February 2019 and by May 1, she was having her first chemotherapy. Then it was pretty much eight months of chemotherapy of different types.

“Obviously I chose to put my career on hold to be at home with her and help with just support and whatever I had to do.

“You fear the worst at that moment, thinking, ‘Is it the beginning of the end?’ All these crazy, ridiculous things go through your mind. We have three kids, and I was thinking, ‘How am I going to do this?’ In the end, the doctors and oncologists made us feel so welcome and said to Jennie, ‘Listen, you are not sick. You have a problem, and we are going to fix it.’ That’s how we lived.”

How is Jennie doing now?

“She is doing great. I was at the races in Sweden a few weeks ago and she had her regular follow-up with the oncologist. We have become such good friends with the oncologist and the whole cancer team. They are just really good people.

“She has been on a trial drug for the last three years to prevent the cancer from coming back. This trial drug brings all sorts of side effects and bone density issues and things like that, which she has been following up.

“But she’s just about to finish this trial. They said she was one of the select few that did it and after all their research, they are 100 percent convinced that this drug protects women who have had breast cancer stage two or higher from getting it again after treatment. It eliminates any chance of that happening. She got that news a few weeks ago and that’s super cool.

“She can live with confidence. We have met some amazing cancer patients and people who have been through this stuff over the years, especially in the treatment centres where she had the radiation and chemo. You meet some really great people. Everyone shares their story and when you have been touched with this, it changes you. It changes you as a person, an individual, a family and it changes you emotionally.”

Was it a tough decision to step away from the sport in 2019 and then retire a year later in 2020 – or did Jennie’s support throughout all the years you spent on the track make it easier?

“That was the biggest topic of our conversation. She was there for me, and she never said a word about the stress of what I did. She never tried to slow me down. She was the one who pushed me when I tried to slow down. In the end, she is convinced the stress played a large role in the things that have happened – not that this was just me. It was a no-brainer when decision time came.”

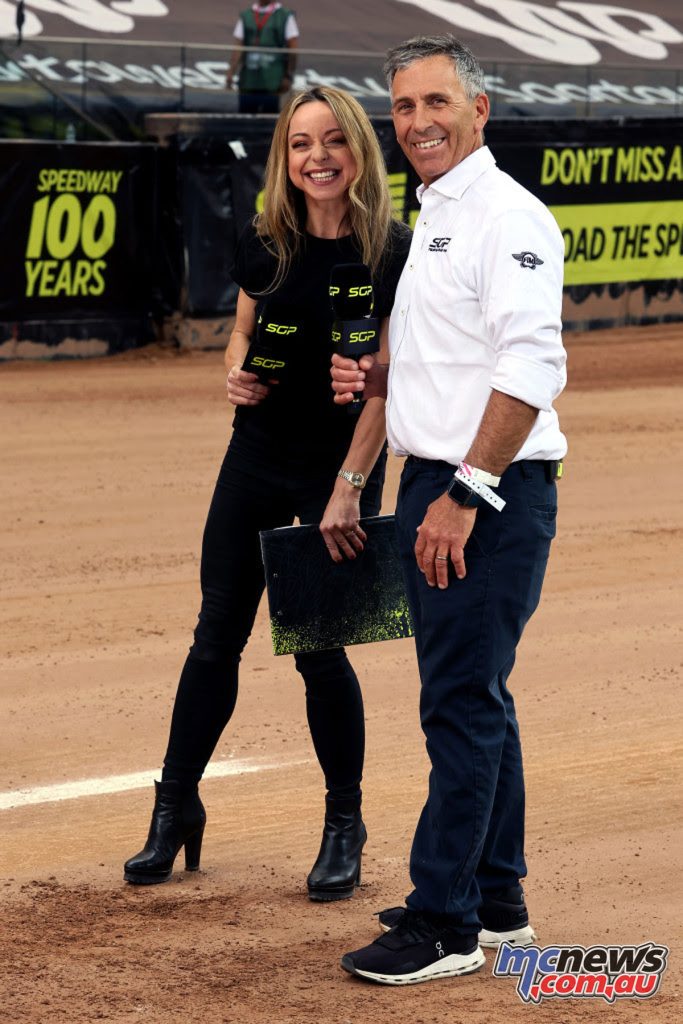

After a spell coaching Wroclaw in the PGE Ekstraliga, you have joined Warner Bros. Discovery Sports’ Speedway GP broadcast team for 2023 – bringing your expert analysis to fans around the world. How are you finding your new role in the sport?

“It’s great. It’s really cool. Warner Bros. Discovery are amazing. We were talking last year about doing some TV stuff, but it didn’t work out. Then this year they called a little bit later. I was supposed to be working with Wroclaw, but then that didn’t work out.

“They called and asked if I wanted to be a part of their broadcast team and of course, I said, ‘Wow, this is cool!’ We made a small agreement, and I am doing eight rounds of the Speedway GP series with a pre-show and a post-show. I am building up to see if we can do more in the future.

“I really enjoy it. It’s a different role for me. I love working with Scott Nicholls, Paul Whipps, Julien Legoux and all the production crew – everyone who is there. They really make you feel welcome and educate you along the way.

“They are learning from me too with my experience and from everything I have done in the sport. It has been exciting. It’s a new challenge and it is my new race – learning how to talk on the microphone and do it right. I really enjoy it and I am learning something new every time.”

Working on the Speedway GP live show may not be as exciting as racing in the series, but does it still give you a buzz?

“It’s still a buzz for sure. I dig it! It’s a whole different ball game. I am trying to be more relaxed and live for the moment. Sometimes you get excited, start saying too much and get ahead of yourself.

“But they have really taught me to take a breath and explain myself. They tell me, ‘Everyone wants to hear what you have to say, so don’t be in a rush to get information out. We have time. We want good quality info and you have got that, so enjoy the moment.’”

Thanks very much for speaking to us, Greg – one of Speedway GP’s all-time greats.