Ivan Mauger

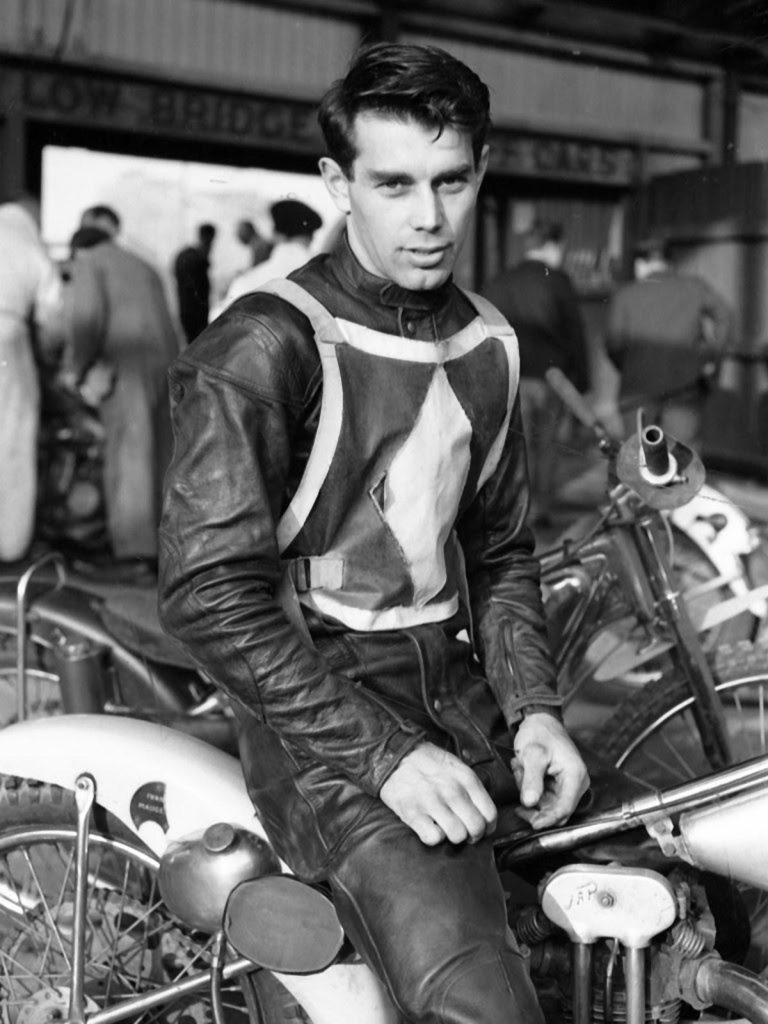

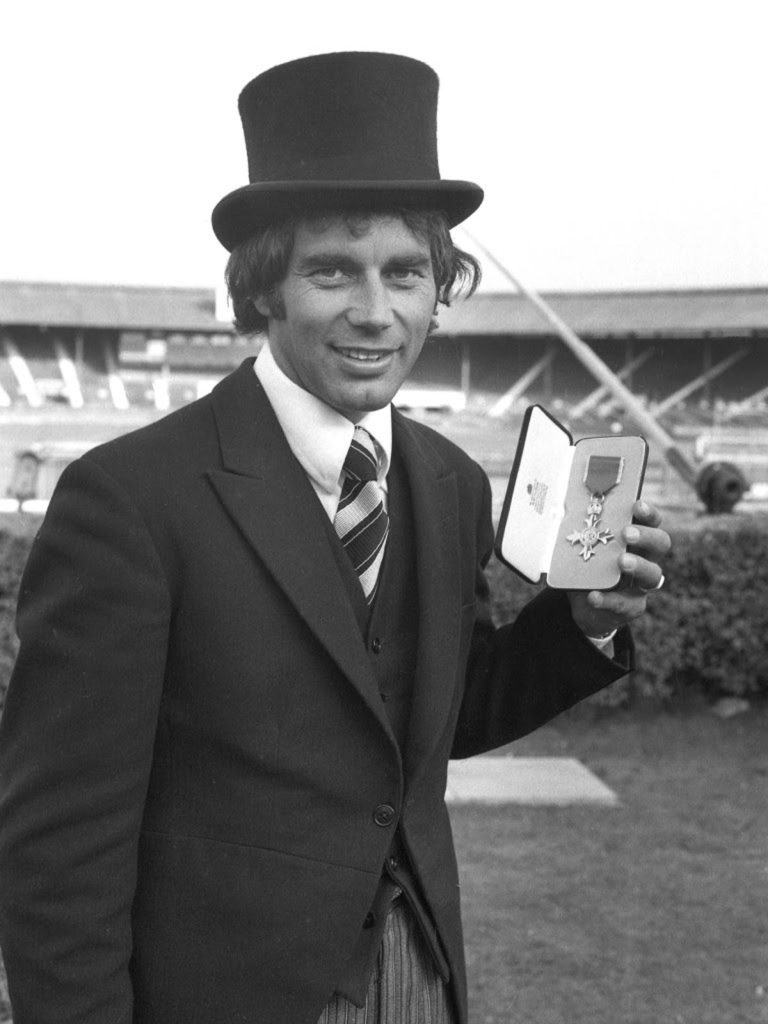

When it comes to FIM Speedway’s World Final era, New Zealand great Ivan Mauger stands head and shoulders above the rest. He remains the only rider to have won speedway’s biggest prize three years in a row from 1968 to 1970, before becoming the sport’s first six-time world champion by winning three more in 1972, 1977 and 1979.

While Mauger passed away in April 2018, aged 78, FIM Speedway promoters were determined to tell the story of the 20th century’s greatest speedway rider in his own words – as with all FIM Speedway Stars of the Century.

Here you’ll find extracts from the Kiwi icon’s fantastic 2010 autobiography, The Will to Win, with the kind permission of Ivan’s wife Sarah (Raye) Mauger, who we acknowledge as the copyright holder of the book – written by Ivan alongside speedway journalist Martin Rogers.

Enjoy insight into what makes an FIM Speedway world champion and get a taste of his incredible recipe for success in the final chapter of FIM Speedway’s Stars of the Century series, celebrating 100 years of the sport in 2023…

To order yourself the full book, chuck ‘Ivan Mauger: The Will to Win: The Autobiography‘ into your favourite search engine and find an online or local stockist.

Ivan on dreaming big and learning from the best…

“In a largely individual sport, you need to be your own best judge, critic and motivator. I had big dreams, took the risk to go to England, made the commitment, turned it into reality and always believed in myself to make it happen.

“World and Olympic champions in a variety of sports also had a dream and were able to imagine themselves standing in the winner’s position on the podium. Whether attending Sportsman of the Year presentations, TV personality shows or similar functions around the world, I came across many greats, male and female, who had the same philosophy of mind power and visualisation.

“Organisers would put a lot of effort into table plans at these events, but when the time came for everyone to be seated, no-one could care less.

“I got into a routine of arriving early to see who was supposed to be where and then moved myself to sit next to someone sure to be really interesting company.

“I have often wondered if (New Zealand mountaineer and explorer) Edmund Hillary or (British athletes) Roger Bannister, Sebastian Coe, Daley Thompson and a few others figured it was more than a coincidence that we were seated next to each other on several occasions.

“Achieving the correct mindset to succeed in speedway is not so different from what sprint runners and swimmers have to do. Their preparation for the starts is similar to what I had to do, especially at international and world championship events.

“Approaching the start line with almost 100,000 spectators and millions of TV viewers watching and a world title just around the corner can be a very lonely place. I learned that in any sport or field of human endeavour, all the great achievers had a dream and the ability to identify where they were going and what they wanted to be.

“These are not the dreams everyone has at night when asleep – they are the dreams you have in an alpha state of consciousness. That is when you have the ability to slow down your mind and concentrate on mind power and to be able to visualise what you want to do next year, in six months, next month, next week or tomorrow.

“Sometimes the process can be a lengthy one. It took me from the age of 15 to almost 29 before the dream of becoming world speedway champion came to fruition.

“When we came to England for a second time, it was with the express intention of making up for five lost years. I was 18 when I went back to New Zealand in 1958 after two seasons at Wimbledon where I hardly got a ride, and 23 when I returned to ride for Newcastle in 1963. Many images coursed through my mind, but the picture of standing on top of the podium, listening to the New Zealand national anthem was a recurring one.

“As my career and my life unfolded, other more specific plans would be months rather than years in the making, like my sixth and last speedway title in 1979.

“The 1978 World Final at Wembley was my worst. I finished eighth after never having been placed lower than fourth in all my others. My night went pear-shaped after my engine seized going into the pit turn in my first race when I was in tight company with Ole Olsen and Gordon Kennett, and I had to lay it down.

“While I was lying on the track, I told myself it would be a different story next year and I had my visualisation working from that second until the 1979 final in Chorzow. It took me a year of getting my head around it, plus determination and mind power to succeed in Poland and erase that race and the 1978 final from my mind.

“I learned a tremendous amount about mind power from fellow guests at those celebrity functions by asking them certain questions and knowing the answers I would give if asked those same questions. Almost without exception, they gave me familiar answers, which were all positive. That told me we had very similar ideas when it came to goal setting and using the power of the mind to anticipate different scenarios.

“There have been many stories written about me in relation to my mind power, concentration levels and visualisation techniques and so on – most by people who do not possess any of these attributes to any significant degree and consequently have little or no understanding of what I was about.”

Ivan on making the move from New Zealand to Britain…

“As a schoolboy sportsman, I travelled to a few regional centres on the South Island, but I had never been out of New Zealand. My wife Raye was one up on me, having done the round-the-world voyage as a nine-year-old when her parents moved to New Zealand. She recalled not only the excitement of the trip, but also had her memories of what England was like, in and around her birthplace of Carlisle at least.

“My awareness of the UK, even though teachers would have preferred me to know more, was limited to the names of various speedway tracks. Miss Saunders at Opawa School had been to England for a couple of years, but she couldn’t throw much light on places like Wimbledon or Belle Vue.

“I knew Wimbledon was in London, which was assumed to be the centre of the universe. I knew most speedway riders came from England, that Kiwis and Australians who went there to race were part of the scenery, and apart from Sweden, there appeared to be very few other countries involved.

“My sources of information were not school textbooks, but from reading Speedway Star and Ice News. That, and gossip around the stands and terraces at my local track Aranui, when an exotic overseas star breezed into Christchurch.

“Full of excitement and still on a high after our wedding, Raye and I took the ferry from Lyttleton on the South Island to the capital Wellington for our honeymoon. We stayed with Raye’s cousin Leslie and her husband Ralph at Karori near Wellington.

“After our short stop there, we boarded the New Zealand Shipping Line’s Rangitoto for our trip to England in 1957. The 22,000-ton liner carried 460 passengers, and it took more than a month to circle the ocean via Pitcairn Island, Panama and Curaçao.

“Because our tickets had been booked at different times, we had to make do with separate cabins, and that apart, we had plenty of entertainment on board. But we were both impatient to get to England for the real adventure to begin.

“The voyage completed, at last we got off the boat, grabbed our belongings and found the train into London. We knew nothing and had little idea of what to expect.

“Our first impression of England was spotting row after row of identical terraced houses, all with chimneys. We had never seen a double decker bus and didn’t know what it was! Nowadays, young kids jet into Heathrow and they know what to expect because hardly a night goes by when there’s not a shot of London on the TV, a movie or an English show. They know all about England from five years of age. There’s not the same mystique.

“The weather was much colder than we expected as it was early spring, but we did not let it concern us, then or in all the time we lived in England. We were there for speedway and the weather was not a problem to us at all.

“Soon enough we had to fit in the compulsory sightseeing, doing the tourist things like watching the pigeons in Trafalgar Square, and walking round Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Street.”

Mauger may have ended his career as one of the sport’s all-time greats. But things didn’t go to plan in his first attempt at making it in the UK, prompting him to head back to New Zealand after just two seasons.

“Success can be a great stimulant and aid to further achievement. If you have been there and done that, you will know and understand the process involved in obtaining the desired outcome.

“But disappointment and failure are an equally powerful motivational tool if applied effectively. My early career had its fair share of frustrations, and the trick is to learn from every experience and emerge stronger and wiser. That’s the lesson to be taken from adversity.

“A pivotal moment for me was standing on the Tilbury dockside in 1958, watching Raye and our oldest daughter Julie sail off to New Zealand – just a year after the two of us, newly married and with little more than a pocketful of dreams between us, had arrived in England with high hopes and expectations.

“When I first started at Wimbledon in 1957, the greatest shock was seeing how fast everybody was as they raced around the track. I got to England and saw those guys riding round full throttle, going faster than I’d ever thought. I’d always imagined New Zealand legend Ronnie Moore was the only one who did that. I couldn’t believe it and had completely underestimated the standard.

“Even though my first laps had not been anything to write home about, (promoter) Ronnie Greene told me I would be in the Wimbledon team to face Sparta Wroclaw, a Polish touring side, in the first home match of the 1957 season on Good Friday.

“Against opposition which turned out to be of pretty ordinary standard, I managed one point from two rides as Wimbledon cantered to a 66-30 victory.

“But it was not enough to earn me a place in the first official team fixture at Rayleigh in the Britannia Shield. Instead, for my next opportunity, I had to drive to Liverpool for a challenge match against Oxford and I filled in for the Cheetahs, again, scoring one point. After that, it was a case of hoping there might be a second half race for me on Monday nights. Just two more senior appearances came my way that season, at home to Norwich in the Britannia Shield, where I failed to trouble the scorers, and a National League visit to Ipswich, which produced one third place.

“Raye and I survived our first English winter, but it quickly became evident we were running out of funds, especially with an extra mouth to feed.

“We came to the conclusion that it would be better for Raye to take Julie back to Christchurch, and for me to stay behind and concentrate all my efforts on making some headway in the 1958 season before my own return to New Zealand. We had to borrow from our parents to help her get home.

“Almost a year earlier, we arrived to start the great adventure. Now I was watching my wife and baby board the Rangitoto at Tilbury to undertake the return journey to New Zealand. This was a crucial moment not just for my career, but in our life. We had no idea what the future held, no certainty that my second year in England was going to be any more rewarding than the first, no guarantees as to how any of us would cope with a lengthy separation.

“What made it worse was the fact it took hours at the dockside to process the passengers – not like the speed of international travel today – and the longer it went, the more upsetting it was.

“We were there from early in the morning, with passengers getting on the boat and everybody finding out where the cabins were and so forth. Then came an announcement over the tannoy for all non-passengers to leave the ship.

“Even then those who were going would stand at the ship’s rail and relatives and friends would be standing on the dock, watching and waving. Finally, the boat slipped its mooring and sailed slowly down the Thames.

“I just stood there crying, watching the boat until it sailed out of view. I have never forgotten the feeling, standing there for so long alone with my thoughts. But when the Rangitoto was out of sight, I got into my little £15 Ford Thames van and drove back to our flat.

“That was when I vowed to dedicate myself to doing whatever it took to become world champion, and that I would never again be in the same position. I said to myself 100 times over, ‘I’m not going to be in this position next time we come back to England’.

“The 1958 season turned out to be another hard road but whenever I asked myself, ‘What am I doing all this for?’, I could also answer myself… to be a world champion.”

Ivan on finding a winning formula…

“From the time we went back to England in 1963, every season revolved around the desire to be a champion. You have to want something to achieve it, and you have to be prepared to cultivate mental strength and strategies to deal with whatever obstacles there may be along the way.

“The World Championship was at the centrepiece of everything. I knew most of the tracks where World Finals and the various rounds were staged and pre-planned the engine settings, compression ratios, ignitions, tyre pressures and even the type of tyre best suited for each of those places.

“Advocates of the Grand Prix system reckon it is a much tougher road than it was in the days of the old one-off World Final. What they overlook is that after a series of qualifiers, semi-finals, a British Final, maybe a British-Nordic Final and, depending on where the final was, there would be an Intercontinental or European Final to negotiate. This all added up to a procession of hard qualifying meetings, which required a place in the top handful to qualify for the next round.

“As the later stages were all knockout affairs, there could be a slim margin for error, especially if there was a mishap or the bike stopped. There were no second chances.

“To ensure nothing was missed in the preparation, I placed a high priority on my ‘self-time’ and would go to a quiet place. If we were in England at the start of the year, I regularly went to the moors near Buxton and sat down to think and plan what I was going to do during the year.

“When we were in Australia, I set off to try to find a wooded area or maybe a secluded spot in the sand dunes. If people were looking for me, Raye would just say I had gone away for a while and would be back later in the day. Sometimes it took me only an hour or so to crystallise all my thoughts and other times it took me several hours.”

Mauger on his legendary reputation for lightning starts in an era when riders could move at the start line and touch and roll into the tapes before the start of a race …

“A lot of observers reckoned much of my success was as a result of my ability to get out of the start. I did it so often and so consistently that there were plenty who questioned the legality of my methods, but that is a price you pay for regularly succeeding where others are found lacking.

“No doubt a lot of people found the preamble and the delays frustrating. But in an era when tapes offences often went unpunished – unlike recent times when an infringement at the start can result in immediate disqualification – you needed to be mentally sharp.

“With the old starting system, there were loads of riders who were not clever starters at all. They were simply what I called ‘chancers’, who just dropped the clutch when they thought the tapes were going up. To succeed under that starting system, you needed to be dialled in, have massive concentration levels and also have a very clear perception of the mental strength of the guy who was going to press the button – the referee!

“I used my thought transference powers many times on officials. When they used to give the riders a briefing in the dressing room before a meeting, they regularly gave their ‘starting system’ speech to tell everyone they would disqualify us for such and such an offence.

“My mental powers and visualisation gave me the ability to read if they had stronger mental powers than me and, over time, I was able to assess if they would make decisions that were unpopular with the crowd. I figured most would not. One look often confirmed most would not do what they had just told us.

“The rule whereby a rider is excluded for touching the tapes is the single best rule introduced into speedway. It was in most European countries domestically for 10 years before the British League and FIM thought of it.

“A lot of riders would regularly push the tapes in British speedway and FIM meetings and make a big percentage of their starts. Okay, I was one of them, but mostly that was part of the strategy so any ‘chancer’ would not do it.

“The system of the day more or less made it a necessity to push the tapes and hold up proceedings long enough to force the referee into not allowing the chancers to go. But you had to know when the official would break them on your front wheel – that’s when it was vital to know if you had stronger mind power than the referee.

“The fact is I made a bigger proportion of my starts in Europe on Sundays on a speedway bike, a long track bike or a grass track bike when we all had to sit still. When I was confident no-one else would move, I was better able to concentrate on the terrain, surface, grip, the amount of throttle required, and it didn’t matter what type of discipline it was or what type of bike.

“In my 30 years as a racer, there were a dozen or more starting systems tried in the various branches of the sport. It’s an old refrain that good starters are good starters no matter what the system. The same guys get to the corner first every time.”

Ivan on preparing for success…

“If you want to walk a different road to the rest, which I did, then my best way of ensuring my performance was at the desired level was to perfect the whole process and let the outcome take care of itself.

“Having the sense of well-being physical fitness brings was as important nowadays as ever it was.

“For more than 10 years, I was racing for around 46 weeks of the year and calculated in ten and a half months, there could be at least a dozen crashes and a percentage of them would probably hurt.

“When I had accidents and ended up with a bad knee, hip, ribs or shoulder, I was able to overcome the bangs and bruises much quicker than rivals who used to come into the dressing rooms and complain about a sore knee or a sore shoulder. If the injuries were serious, I tried to find a way to minimise the effect and not give in to the discomfort.

“Ordinarily, I expected to maintain a high standard of fitness because I made sure I worked harder at it than anybody else. Training with the Manchester City footballers, as I did for several years, helped me achieve a level few if any of my rivals could approach.

“Riders may be required to be in a stadium from early in the morning for machine examination and other commitments. Much of the time they are on their feet and, when the most important race of the day comes round, that might have stretched out to several hours.

“If you had ambitions of winning, you could not afford to be tired in any respect because as soon as you are physically tired, you become mentally tired. When you are lining up for a heat which might decide a world championship, you need to be sharp.

“Getting my mental toughness into gear was the password to unlocking the right solution to whatever situation presented itself. Riders, officials or press people who saw me with my eyes closed in the dressing rooms assumed I was sleeping.

“I vaguely heard them in the background but took none of it on board. I was not asleep but going over every start in all my races and working out plan A and then plan B (there was never time for a plan C from the start).

“I had a plan if I was leading out of the first corner and another plan if I was second or third. Each of my rivals had their own preference to use different parts of the track, so they were all creatures of habit and therefore quite predictable. That made it easy to choose what part of the track to pass them if they made a mistake.”

Mauger realised his FIM Speedway World Championship dream at Gothenburg’s Ullevi Stadium in 1968, before retaining the crown at Wembley in 1969…

“On reflection, those six world titles were a payback for years of hard work and attention to detail, the rewards all the sweeter following the struggles and many disappointments which littered my first few years of racing.

“Winning my first world crown in Gothenburg on Friday, September 6, 1968, was a moment I had been waiting for half my life, since that first ride on the beach as a schoolboy hopeful in New Zealand.

“Of course, my confidence was enormously boosted by becoming world champion. But only three riders, Jack Young (1951-52), Barry Briggs (1957-58) and Ove Fundin (1960-61), had managed to win back-to-back World Finals.

“Defending the world title for the first time in 1969 was another new experience but, by now, other people’s expectations did not bother me. As long as I was comfortable in my own skin, happy with how I was riding and the bikes were working, it was a question of getting the job done.

“I knew I could handle the pressure and all I had to demonstrate to myself was that this was another year, another opportunity. And there was no need to venture outside England as the always-alluring goal of Wembley was waiting at the end of the championship road.

“What added to a special occasion was that not only was Raye there again to witness everything, but Julie, my son Kym and youngest daughter Debbie were up in the stands. So was my mum Rita, absolutely electrified by her first overseas trip and blown away by what possibly was the most exciting occasion of her life.

“Double world champion had a nice ring to it. I enjoyed the sensation of winning once more sufficiently to make a mental note to do it again some time.”

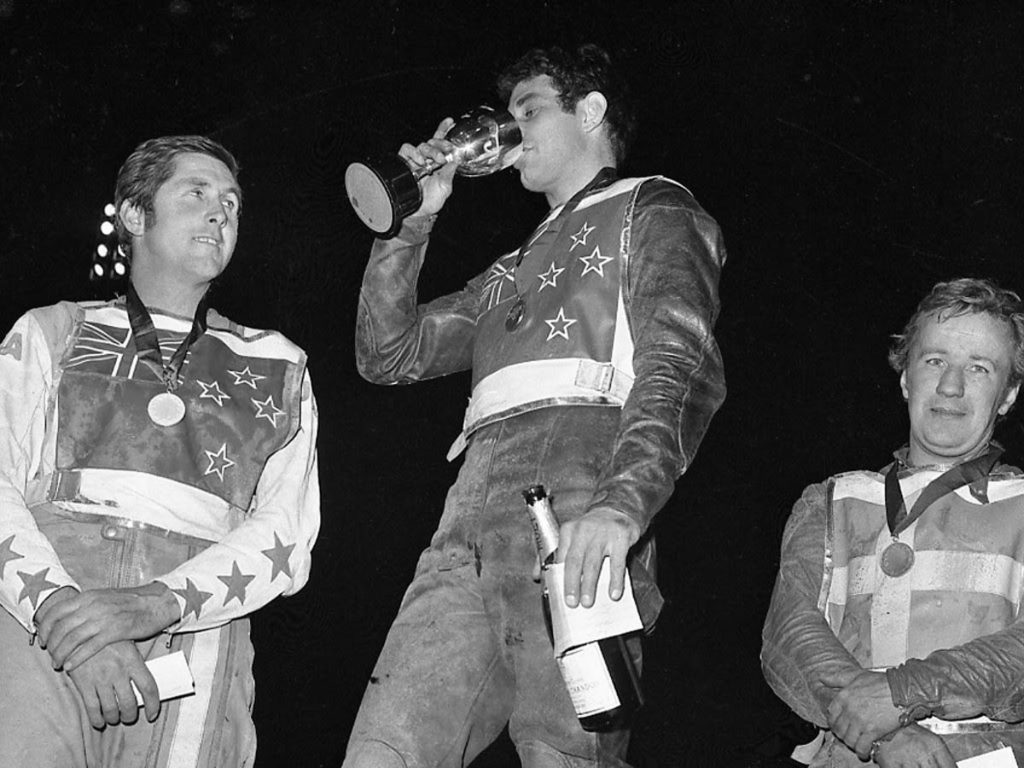

Mauger made it three in a row as Wroclaw’s iconic Olympic Stadium staged Poland’s first-ever World Final in 1970 …

“Nobody had achieved three in a row. Some considered it could not be done. And certainly, most observers thought a western rider had little chance of winning in Eastern Europe.

“In the circumstances, I considered my win in Wroclaw in 1970 the absolute best that I had ever raced, and I still do. The Poles and Russians were the emerging force in the 1960s and began to produce riders who were capable of beating anyone, anywhere. They seemed able to adapt to racing in Great Britain and Sweden better than our boys could cope with conditions behind the Iron Curtain.

“Trips out there were often very intimidating, the environment and atmosphere quite forbidding. A lot of the Eastern European tracks had a bit of an adverse camber on them and were very wavy.

“I had been at Wroclaw in 1966 for a Poland-Great Britain test match, followed by the World Team Cup Final – without much joy. But in 1968 at the European Final, I got 10 points, finished fourth and broke the track record. Psychologically that was something of a breakthrough meeting for me.

“Trying to win in Wroclaw in 1970 was the biggest test. Everybody knew the Poles would be fired up big time. We had been there for four days, and it was extremely hot. No surprise then to find my position was in the hottest part of the pits.

“At a World Final, officials complained if I moved from my allocated pit space, but there were many reasons why I often did not conform. At some stadiums, the spectators were a nuisance on certain sides, but for the most part, foreign organisers only had thoughts for their own riders.

“Visitors were allocated the hot and sunny positions for afternoon meetings or cramped and poorly-lit areas for night events. My race crew always knew where we wanted to be, so they commandeered the positions which suited us best, regularly inviting protests from riders, team managers, referees or the clerk of the course. Almost invariably, we stayed where we wanted to be.

“It took an almighty row with a gang of Polish officials in Wroclaw, but we moved out to the back of the pits, shaded by a huge concrete pillar. We were quite a bit away from the gates which led on to the track but in the cool and relaxed.

“The clerk of the course and the pit marshal kept getting the western riders on to the track and sitting on their bikes in the heat. Meanwhile the Polish riders were being wrapped in damp towels and making the others wait. I quickly realised that ploy was happening and had my guys stationed at various locations passing the word to each other until they reached (my mechanic) Gordon Stobbs and me. My signals told me not to bother to start getting ready until the Polish riders were on the track and sitting in the heat.

“It was a day on which everything had to be perfect – the build-up, the bikes, the mental and physical preparedness. One mistake could have ruined everything. But I didn’t make one. Five races, four copybook laps each time. The Polish contingent didn’t have an answer. World champion. Again. And they said it couldn’t be done.

“This was and remains my ultimate moment in speedway. The bumps, the backslapping, all the usual outpouring of emotion and celebration felt fantastic.

“Polish television whisked me off for an interview. That duty done, I was able to greet Raye who had come down from the stands, her white coat streaked with grey dust from the track, and we reflected silently for a few seconds on the enormity of it all.”

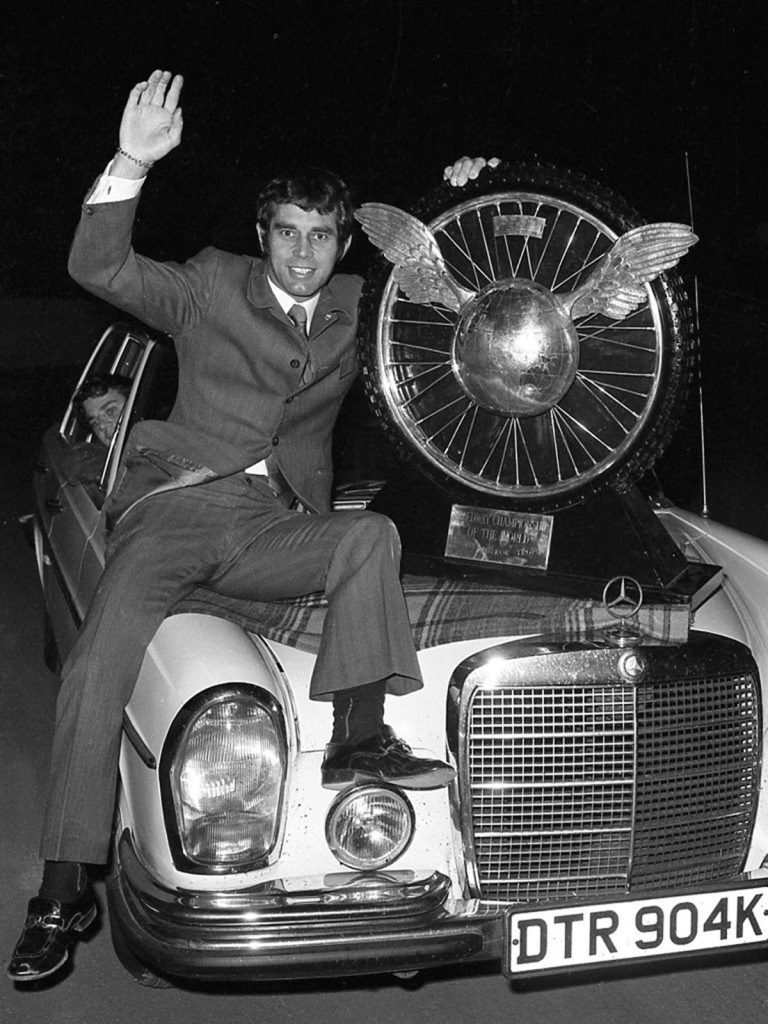

Having secured world title No.4 at Wembley in 1972, Mauger went on a barren run by his incredibly high standards. But he never lost his thirst for gold, ending his five-year wait for No.5 in Gothenburg in 1977 …

“There is nothing better than achieving something after almost everybody has decided that you can’t do it. After winning a fourth world speedway title a month short of my 33rd birthday, I never doubted my ability to add to that total.

“It wasn’t a question of trying to outdo Briggo, who signed off with four, or catch Ove Fundin, then on top of the all-time pile with five. It was all about continuing to race because in my heart of hearts, I knew I still possessed the desire and the capability.

“That was the case for five years from Wembley 1972, right up to the moment coming off the final turn of my last race in the 1977 World Final in Gothenburg … with five digits aloft to remind the doubters that I was now a five-time winner and counting.

“Clinching a third World Long Track title in 1976 after a long dry spell was one of those occasions which reminded me what winning a world championship is all about and how it feels.

“I went to Gothenburg in 1977 as well prepared, as organised and ready as for any World Final. Nobody could have faulted my attention to detail. My tuner Guy Allott had worked every waking hour to ensure the Jawa motors were purring perfectly.

“Come the interval, Peter Collins, Ole Olsen, Michael Lee and I had all dropped a single point and the rain, which seemed to be a traditional part of almost every final in Gothenburg, was threatening to become a real factor.

“There was a stroke of good fortune in heat 13, which had to be re-started after Egon Müller had crashed. This time I got the better of Peter and had 11 points in the bag while other contenders still needed to get out there and deliver.

“Michael faltered, Ole did not, and the draw found the three of us in heat 18 with all to play for. By this stage the scores were: Mauger 11, Olsen 11, Lee 10 and Collins – due out in the last heat – also on 10.

“That meant Ole or I could wrap up the title by winning, and Michael was right in the mix. PC meantime could only sit and wait to see from the outcome of this race if he was still in the hunt.

“By now the rain was really sheeting down, the track surface was a skating rink, and, typical of the distorted thinking which can apply at major sporting events, if it hadn’t been so important, the obvious and only decision was to call a halt and send everybody home. But that was never going to happen. Sure, it was a lottery, but I figured I had a better idea than most of what the winning numbers might be. If ever there was a case of summoning up all my experience and calling upon the lessons learned over 20 years, this was it.

“After a crash between Australia’s Johnny Boulger and Ole in the first staging of the race, I made a dream start in the re-run and the four laps were almost a formality. Once I was gone, not even Olsen or Lee would make any impression on me. Coming off the last corner, I saluted the crowd and felt the emotion wash over me.

“As if I wasn’t wet enough, the next drenching I got was from Ove Fundin, whose record of five wins I had equalled. He poured a bottle of champagne over my head and Kym, in the pits with me for the first time at a World Final and not yet old enough to drink, copped half of it.

“Ove was generous with his congratulations. He alone knew exactly how much hard work had been involved. His fifth title also came after a few unproductive years during which every man and his dog had written him off as a spent force.”

Mauger defied a tough 1978 World Final at Wembley to make a winning return to Poland, sealing a record-breaking sixth FIM Speedway World Championship at Chorzow’s legendary Silesian Stadium in 1979 …

“Even as I savoured the joy of winning in Sweden, I knew there still would be critics who dismissed it as a flash in the pan, the last hurrah for an ageing warrior, which meant five still would not be enough. From my perspective, winning another world championship at Ullevi was confirmation that my own self-belief through some difficult times had been entirely justified; and I enjoyed the moment sufficiently to like the idea of doing it again.

“Sure enough, when title No.6 materialised in Poland in 1979, I did again enjoy the uniquely personal and by now familiar sensation of delight, relief and fulfilment that routinely accompanies such a meaningful achievement.

“I did win a couple of races in the 1978 World Final, but eight points was my lowest score in all of my World Final appearances. It’s amazing what a difference losing makes. Hordes of supporters wanted a piece of me afterwards. I must have qualified for the sympathy vote because the queues of autograph hunters and well-wishers seemed endless. It was ages before I could get away to the official banquet.

“My appetite was not at its best. But my hunger for another winning night was still intact. Defeated champions invariably say, ‘I’ll be back’ after a defeat, and I was no different. The thing is, I meant it. I was absolutely determined to give one more supercharged effort to the 1979 campaign.

“I felt relaxed about my chances. It was a bright, clear, exhilarating autumn day in the Polish sunshine. There were friendly, supportive faces all around – including Briggo, with whom there was so much shared history.

“You might think after having been there and done that a few times, the sensation of pleasure and the emotion would be relatively low-key. You would be wrong. I couldn’t have been more excited or delighted. Raye, Julie and Debbie, from high up in the stands, made their way down to join the throng of well-wishers.

“These moments always tend to pass in a blur. So many hands to shake, so many congratulations to receive. Through it all, there was the clarity of realising I had passed Ove Fundin and become the first rider to be a six-time world speedway champion.

“Christoph Betzl, a German long track specialist, friend and rival, who had made it through to his solitary World Final, had worn the No.6 race jacket. Fortunately, he was only too delighted to lend it to me and that is how I was able to hold aloft the significant ‘six’ from the podium.

“It remains one of the most familiar images from my career, and I never tire of seeing it. Two titles in three years should have been sufficient to demonstrate I was not a spent force, so that added to the satisfaction.”

Ivan’s words of advice for the next generation …

“There is no substitute for hard work and dedication. Tell young riders if they seriously want to be successful, they have to love what they are doing, eat and sleep speedway, train hard, be dedicated and gather good loyal people in their support team.

“Whether at the start of a career or any later stage, application is all. Chart everything, analyse everything, and treat your favourite engine like a baby, record results. weather conditions, particular races, best gates, tyre pressures and gear ratios.

“If all the ingredients are there, winning should become the fun part. I refused to contemplate failure even though a lot of people described me as one when I was 17 and 18. The moral of my story is that the ones who make the grade do so because they use their brain as well as their throttle hand, although I’m not sure too many of today’s youngsters think enough about the psychological side or the detailed preparation required to go all the way.

“I hear too much of them talking endlessly about who is the best tuner. Bikes are still 500 cc single cylinder race machines just as they have been for more than 80 years. And it’s who is on them that matters the most.

“My greatest stroke of fortune was to be supported on every step of the journey by Raye. She continued to believe in me even on those odd occasions when I may have been feeling sorry for myself and wondering if there might not be some other way of spending my time.

“Fortunately, I always managed to answer my own question. You can’t put a price on that most basic human emotion – the will to win.”