ASBK into the future

A few topics up for discussion

Elsewhere in the world, WorldSBK, British Superbike etc. there are attempts made at achieving parity in Superbike competition. For example, all bikes are limited to an absolute maximum of 16,000 rpm in BSB, but only the Ducati is allowed that full 16,000 rpm as it can achieve those revs in standard trim. Other Superbikes are allowed 750 rpm above their normal standard street rev limiter.

In BSB though all competitors are allowed to change camshafts, valve springs, modify cylinder heads, change con-rods, almost all the gearbox internals are able to be changed, radiators, the list goes on… Things are even more open in World Superbike.

Let’s look at Yamaha’s YZF-R1M as an example. In standard trim the YZF-R1 makes its 198 maximum horsepower at 13,500 rpm. But the Yamaha revs on to 14,500 rpm, and thus the rev limit in BSB is set at 750 rpm above that standard limiter as per all machines, pegging the BSB Yamaha machines to an enforced rev limit of 15,250 rpm. And of course with such wide scope for internal modification the Yamaha can make power all the way towards that 15,250 limiter. And they did win the BSB championship this year.

In our ASBK competition, where basically no work is allowed inside the engine, the Yamaha revs to around 14,500 rpm and has no hope of staying in the slipstream of the Ducati. If they get off the corner together, the Yamaha can’t even stay with a Ducati to the halfway point of most straights, let alone when the Ducati really gets wound up in the upper cogs. The power difference is huge, probably 40 horsepower or more.

Obviously you build a faster motorcycle you reap the rewards, but sanctioning bodies elsewhere across the world have been taking significant steps to try and equalise the playing field. Will we have to start thinking about going down that route here in Australia?

In ASBK the latest Honda CBR-1000RR-R SP can stay in the slipstream of the Ducati and the BMW M 1000 RR is close also, but overall the Ducati still maintains a top-end horsepower advantage.

Troy Herfoss is the only non Ducati rider to win an Australian Superbike race in the past two seasons and he has done that on many occasions.

Outside of Ducati and Honda, the last other brand to win a Superbike race was Suzuki, and the rider on that GSX-R1000R was Wayne Maxwell at Phillip Island in 2019.

The last Kawasaki victory came at The Bend in 2019, where Bryan Staring came from behind to win all three races, largely thanks to the longevity afforded by the Dunlop rubber that weekend compared to the other competitors. That is, of course, taking nothing away from Bryan, he is a class rider, we all know that.

The last Yamaha victory was taken by Aiden Wagner at the Phillip Island season opener three years ago. We have to go back much further than that for the last win recorded in ASBK Superbike by a BMW rider.

It is pretty clear that today in standard trim, Ducati’s Panigale V4 R really is head and shoulders above other sportsbikes on the market in regards to pure performance and lap times out of the box. That’s a fact, we can’t criticise them for that, Ducati continue to push the boundaries of performance further than any other manufacturer and are a brand whose modern image is forged off the back of exactly that. Kudos to them.

With an aftermarket exhaust the Panigale V4 R makes a claimed 234 horsepower at 15,500 rpm, on a completely standard engine as bought from a Ducati dealer showroom. In race trim obviously that number can be pushed higher again and in ASBK they are permitted to use their full 16,500 rpm and even higher performance exhaust systems. That amount of revs also affords wider benefits in regards to gearing that can save a gear change at certain points on various circuits. This can be quite an advantage on some circuits.

None of this is to take away from what Wayne Maxwell and the Boost Mobile Ducati squad achieved this season. They were not the only Ducati on the grid, but they did score almost twice as many points as any other Ducati rider over the course of season 2021. Wayne has won major Superbike championships on a Honda, on a Suzuki and now twice with Ducati, he would be competitive on any bike in the field and the team prepared a fantastic motorcycle.

In years gone past ASBK have not really taken any significant steps in the aim of achieving any sort of parity. Nor in the past do I really think this has been necessary, but times have changed as the level of performance difference between sportsbikes in this modern era has become so large, as the price of such machinery skyrockets and the specification sheets become more and more disparate.

We all know life is not always fair, and racing is certainly never fair, but around the world most competitions are aiming to achieve some sort of parity in regards to the Superbike category. In fact not only Superbike, but also pretty much every discipline of not only motorcycle, but also most four-wheel racing competition has been increasingly pushing towards parity.

Parity measures are not without their own drawbacks and such a regimen is a difficult thing to design, and even more difficult to then police. I hope we don’t have to complicate matters by going too far down that route, but the conversation does need to be started, just in case…

Electronics

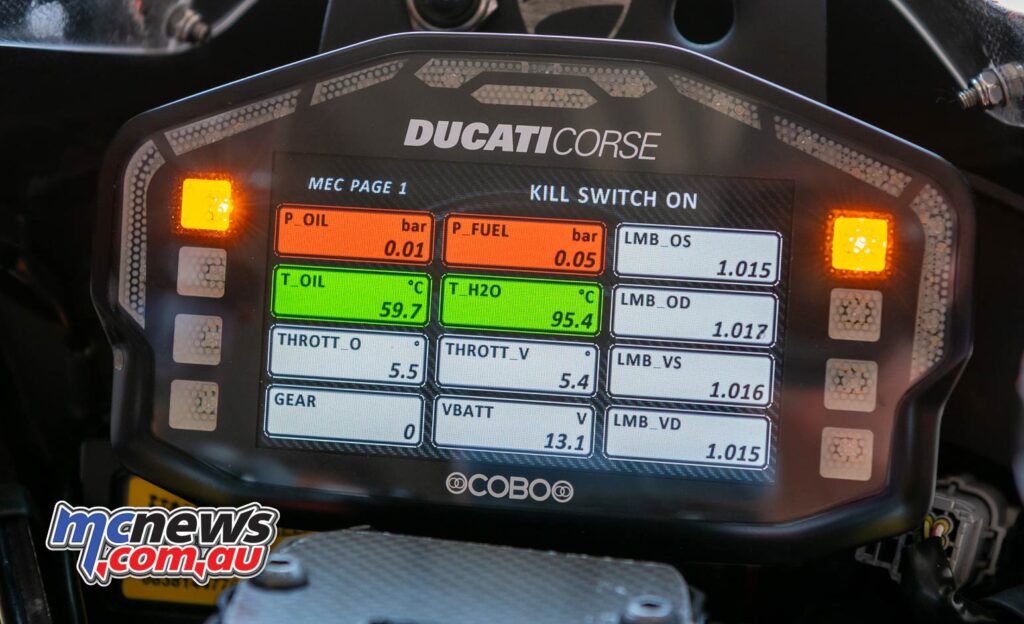

The Boost Mobile Ducati Team were big advocates of the move to a MoTeC ECU and were behind a push for MoTeC to be allowed for season 2021, and believed they had that approval, only to be told late in the piece that they would not be allowed to run MoTeC as Motorcycling Australia chose not to allow that option across the board, and Ducati Australia had not nominated the MoTeC unit as their homologated ECU.

It is up to each motorcycle brand distributor to nominate their chosen ECU/electronics package for their respective motorcycles. Ducati nominated the top of the range Magnetti Marelli option that was available to them. It was the highest performance option and would give their motorcycles the highest performance, thus it was the obvious choice. They do go racing to win after all…

That saw Ducati competitors invest around 50k per rider on the permitted factory Magnetti Marelli ECU and associated components to fit out two bikes.

Penrite Honda then made an almost as significant investment in the HRC kit electronics nominated by Honda Australia, and like Ducati competitors, they will be busy developing their package further in the lead up to the coming season.

There is no point spending money on fancy electronics unless you have the smarts and the time to test and invest in them to make them start to work towards their potential. They are a tool to be used and they need good tradesmen to get the best out of them, it’s not a set and forget sort of business as they come out of the box.

Now here we are on the cusp of season 2022, where a MoTeC M130 ECU with locked down firmware will be allowed for the first time by Motorcycling Australia, for those competitors that choose to use it.

The full functionality of the MoTeC unit will not be available to ASBK competitors as many parameters will be limited by the mandated firmware. This is normal procedure in regards to a control ECU across the world. It can however often end up as a false economy with endless hours still put in to the programming of that ECU to try and gain the slightest advantage in other areas of limited adjustment. For example, the control MoTeC in BSB does not allow traction or wheelie control in simple terms, but top BSB teams can still spend six figures on data/electronics guys…

While a MoTeC unit with rudimentary traction control capabilities will be available to competitors here in ASBK this season, Ducati competitors will still be able to run their high level level Magnetti Marelli electronics. Honda will be able to run their HRC kit and BMW also have access to factory level electronics in 2022. So along with a major horsepower advantage, some will also retain a very significant advantage on the electronics front in 2022.

What do some teams have to gain from using the MoTeC unit with locked down firmware over their homologated kit electronics? I believe in some cases this primarily comes down to the MoTeC unit allowing much more precise engine brake control tuning, in a gear by gear scenario, over the control afforded by their respective manufacturer nominated ECU. In our case that will be primarily Yamaha competitors. The MoTeC unit will also give Yamaha teams more freedom to develop their own strategies for traction, lift and launch control and fine tune them to the preferences of each rider.

BCperformance Kawasaki are also switching to the MoTeC unit for its relative ease of use tuning while trying to achieve improved engine brake control and throttle connection on the ZX-10RR.

However, as stated previously, the traction control responses available with the MoTeC unit approved for ASBK are not in the same league as the capability built into some of the homologated Kit ECU packages that are currently being used.

RPM limits

RPM limits have been published by Motorcycling Australia ahead of the coming season. These are shown below. We also include the most recent rev limits used in BSB, as a yardstick to show what is currently happening elsewhere in the world.

ASBK RPM limits (2022)

- BMW – 15,100 rpm (BSB 15,850)

- Ducati V4 R – 16,500 rpm (BSB 16,000)

- Ducati V2 1299 – 12,400 rpm (machine not eligible for BSB)

- Honda – 15,150 rpm (BSB 15,900)

- Kawasaki – 14,700 rpm (BSB 15,450)

- Suzuki – 14,700 rpm (BSB 15,250)

- Yamaha R1 15-19 – 14,700 rpm (BSB 15,250)

- Yamaha R1 20- – 14,750 rpm (BSB 15,250)

Even if all competitors were forced on to a control MoTeC ECU in 2023, I believe the response times, accuracy and computing power of the IMU and sensors in certain machines will still see them have an advantage.

Unless Motorcycling Australia also allow the IMU and other components to be free for all competitors, or everyone is forced on to an identical IMU across the board to really aim for electronic parity, then it will not be truly equal, but it would be a lot more equal than what we have now, and perhaps still a significant step forward to promote healthy competition. Is an across the board control ECU the road we want to go down…? That is a subject up for discussion.

Cost Caps

We also have the not so small matter of the disparate cost in the base motorcycles currently competing in Australian Superbike competition.

Some in the paddock have started to make a little noise in regards to cost caps.

We include the following price guide, it might not be 100 per cent spot on as prices are subject to change, but is pretty close at time of writing.

Production bike costs compared

- BMW S 1000 RR $23,550 +ORC

- BMW M 1000 RR $50,990 +ORC

- Ducati Panigale V4 R $59,990 +ORC

- Honda Fireblade CBR-1000RR-R SP $49,999 +ORC

- Kawasaki ZX-10R $26,160 +ORC

- Kawasaki ZX-10RR $42,160 +ORC

- Suzuki GSX-R1000 $22,490 +ORC

- Suzuki GSX-R1000R $25,990 +ORC

- Yamaha YZF-R1 $25,970 +ORC

- Yamaha YZF-R1M $34,637 +ORC

With the base machine cost and kit electronics package you are looking at over 60k to put a single M BMW on the grid, 70k for a Honda or over 80k for the Ducati. That is before you race prep’ a bike, get a spare set of rims, or two, and start buying tyres. Then if you want a spare bike…. Basically, that’s 200k before you turn a wheel in anger or even get to a racetrack…

But, racing has never been cheap, and never will be… Outside of the current rules in regards to the numbers of machines that must be brought into Australia for sale before said model can be used in ASBK competition, does the sport want to also put cost caps in place?

The answer is probably no, but there is some noise starting to be made by some that suggest it is worth looking in to. It could even be something as simple as allowing more modifications on motorcycles that come in under a certain price benchmark.

Yamaha still the most common bike on the grid

In regards to the most common motorcycle in ASBK competition well that gong certainly goes to Yamaha in recent years. For this coming season we believe perhaps even more than half of the grid will be on Yamaha machinery.

The Yamaha Racing Development Programme’s assistance to Yamaha competitors no doubt plays its part in this equation, as does the relatively affordable cost of the machine and the purchasing plans Yamaha have in place for supported competitors.

It is also worth noting that Yamaha and their subsidiary companies, such as Yamaha Motor Finance, Yamaha Motor Insurance and their associated Mi-Bike Insurance brand, have effectively underwritten ASBK throughout the modern era. Obviously that shouldn’t impact on how rules are made, but it is worthy of note nonetheless and should be recognised.

Australia is but a minnow in the global stakes

I also recognise that, at present, Motorcycling Australia simply doesn’t have the human resources to set up and enforce a convoluted system aimed at achieving parity.

Likewise, at this point in time I am sure plenty of the competitors also don’t want to navigate that minefield right now as we are so close to a new season getting underway. That ship has sailed for season 2022, but we do need to also keep one eye glancing towards the slightly more distant future.

This is a subject that is worthy of further discussion with a view to 2023 and beyond. I can really only see the performance gaps widening even further than what they are now if our rules do not change with the times. Hopefully I am wrong, it does happen…

There are also conversations needed to be had around allowing the use of more affordable aftermarket rims or swing-arm linkages in a quest to help reduce costs and/or equalise performance for competitors.

Progress being made and more to come

Changes have recently been made to allow the use of cheaper aftermarket sub-frames and dash supports/mounts which has helped competitors in regards to costs.

The change to aftermarket brake rotors that came in a couple of years ago helped some competitors more than others in regards to cost, but was still a useful change across the board.

Some brands of machinery might benefit more than others in regards to runnings costs or performance if aftermarket clutches were also open.

A lot of these, and other, concerns have already been discussed amongst the M.A. Road Race Commission.

It also interesting to note that the decision to allow 1300 cc twin-cylinder motorcycles in Australian Superbike was made in response to a request from a KTM team wanting to have the option of racing a 1290 SuperDuke R. This request and decision was made back in 2014, well before Ducati released the 1299 Panigale that Mike Jones won the championship on in 2019. If competitors want that rule reduced back down to 1200 cc, as per the rest of the Superbike world, then that rule change request must be put forward.

It is up to stakeholders to force change

If manufacturers/teams/competitors/licence holders want change they have to make those requests via the Road Race Commission.

It appears that M.A. take a more reactive route to change, rather than being proactive. That has its pros and cons, but it is clear that for change to be made then the vehicle for doing so is via requests put forward for consideration by the Road Race Commission.

That is the process that needs to be followed and if they want changes that is the avenue they must take. And if their applications are at first rejected, they should then go back to the commission with a better presented case.

Yes this is all time and work, but if you want change then this is the way to go about it. Finding enough hours in the day for that will be hard, but weigh what you might initially see as ‘lost’ hours up against the investment, both financial and personal, you have already put into ASBK, and the time cost versus benefit ratio for the future might start to make more sense.

I also believe that people should not be deemed ‘whingers’ or ‘sooks’ for suggesting or trying to force change, a lot of that attitude is facile and belongs back in the primary school playground. We just need to make sure the changes are for the better.

Even if the Road Race Commission recommends changes on the back of requests they do not have the final say in the matter. Their recommendations need to be signed off by the ‘Rules and Technical Committee’, thus really the buck stops there, but it doesn’t get there unless put through the Road Race Commission first.

Road Race Committee member positions are voluntary and the current board is currently chaired by Jake Skate. Members include Rob Fry, Shaun Clarke, Chris Wain and Mitch Kavney.

Even if the Road Race Commission has deliberated and voted for change, it will get no further than that unless the Motorcycling Rules and Technical Committee chooses to follow those recommendations.

The current Motorcycling Rules and Technical Committee members are;

- Lindsay Granger (Chair)

- MA Board Representative

- Peter Doyle

- Allan Halley

- Garry Lambert

- Sandra Palmer

Road Race Commission Meeting Minutes are published on the M.A. website but are generally quite brief. The notations on those minutes by Motorcycling Rules and Technical Committee are even more curt.

But on the other side of that coin, how many would volunteer their time for free on the Road Race Commission knowing that they open themselves up for broadsides on anti-social media, day in, day out. That will grow tiresome very quickly. I have also known people leave the Road Race Commission out of frustration that their recommendations are simply over ruled by the Rules and Technical Committee.

Furthermore, members on the Road Race Commission are subject to penalties under an NDA confidentiality agreement, thus are unable to make public comment on any of these issues. From a transparency and accountability point of view, that seems less than ideal.

Some Team Managers have suggested they form some sort of alliance to put forward requests for change as a collective.

Or is it time for a single representative put forward by each motorcycle brand, with that group then holding meetings to put forward changes for consideration as a collective? This is what happens in MotoGP via the Motorcycle Sport Manufacturers Association, MSMA.

Starting the conversation….

I will invite various stakeholders to make their informed comment on these subjects, and others, over the weeks and months ahead and hope this can spark some instructive discussion that might shape the future and help ensure that ASBK can remain healthy into the future as the competition adapts to the challenges ahead.

Do I claim to have all the answers? No, certainly not. But there has been a fair bit of talk on this subject around the traps of late thus I thought it pertinent to air some facts and background information here. I am sure many people in racing are not themselves aware of some of the notes I have put forward here, let alone race fans watching on from afar.

Some might criticise me for airing concerns such as these publicly but I am only putting this forward for consideration in the interests of the future of the sport.

Contrary to what many might think, nobody has ‘put me up to this’, or is using me as a vehicle to air their views.

Likewise, I am not making any summary judgments about where we go to from here, I just aim to inform and provide background data to stimulate discussion.

Motorcycling Australia’s Superbike competition was in significant trouble some years ago when not enough people spoke up or were constructive enough to try and change things. I am certainly not expecting or predicting that to happen again, but sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants, and transparency is key as the sport is shaped for the future.

As for those that might claim I have no right to comment, I feel I should remind you that I have missed one round of ASBK this century. The only expense account used to get to those races and cover them is the same bank account that pays my mortgage, and out of that account I’ve already racked up about 10k in logistic costs for the season ahead. Small fry compared to those that stump up the cash to compete and those that support them, but I do have skin in this game nonetheless…

ASBK 2022 is shaping up to be a great season

In the meantime season 2022 is shaping up to be a ripper with more than a few talented riders entering on machines that are more competitive than what they have been on in recent seasons.

If Wayne Maxwell decides to continue with Boost Mobile Ducati he will start as season favourite.

Troy Herfoss will be in much better shape as he continues to build up strength and he was the rider who ran Maxwell closest in 2021 before his injuries in Darwin…

Cru Halliday continues with YRT and the team is more determined than ever to take the title after 15 years without a #1 plate.

Glenn Allerton is fit, loving the new M model BMW and getting plenty of seat time in of late…

Bryan Staring on the Ducati….

Josh Waters on a BMW…

Mike Jones with YRT….

Arthur Sissis ended the season in hot form and will come out swinging…

Daniel Falzon is mending quickly and expects to be hot to trot come season start…

The new BMW Alliance Team on the grid…

Aiden Wagner expected to be on a privateer Yamaha…

Jed Metcher with a bigger and better team around him than he has had before…

Mark Chiodo expected to become more competitive…

Supersport champ Broc Pearson stepping up to Superbike…

Max Stauffer also joining the Superbike ranks…

If Westy can get a competitive and reliable motorcycle underneath him…

Ben Burke is making a return to ASBK on a BCperformance Kawasaki…

Testing is set to get underway at Phillip Island late this month before the season opener takes place at the same venue late in February. Can’t wait…