Triumph Bonneville Silver Jubilee

With Ian Falloon

The public’s fascination with the British Royal family is not a new phenomenon. It extends well beyond popular entertainment for the masses and even motorcycles aren’t immune from this populism. In 1977 Triumph decided to exploit a significant Royal event, the Queen’s Silver Jubilee (25th Anniversary).

At the time the Triumph board included several unpaid managerial advisors, one being Lord Stokes, former Chairman of British Leyland. He suggested Triumph capitalise on the event and managed to obtain Palace approval for a limited-edition model. Thus, each Bonneville Silver Jubilee came with an official commemorative certificate, and it would become one of Triumphs most successful models of Meriden era.

The early 1970s was an extremely turbulent time for the British motorcycle industry. By 1973 most companies had closed their doors and only Norton and Triumph remained. But despite significant government assistance their annual losses were still horrendous.

In an effort to save the industry, Norton and Triumph merged, with production to be consolidated in two factories; the BSA plant in Small Heath, Birmingham and the Norton facility at Wolverhampton. But no one told the workers at the small Triumph factory at Meriden in the West Midlands.

With the threat of closure looming, the Meriden workers blockaded the factory in September 1973, effectively halting Bonneville production for nearly two years.

When production of the Bonneville resumed late in 1975 it was still ostensibly an anachronism in a world now used to oil tight four-cylinder superbikes with overhead camshafts and an electric start. As Triumph was limited in their developmental resources, the Bonneville’s updates were primarily to enable it to be sold in the traditionally profitable US market.

This included a left-side gearshift, rear disc brake and new Lucas switches. Although the revamped T140 suffered from hot running, unreliable electrics and vibration, it still possessed great mid-range power and excellent handling. And the traditional scourge of British twins, oil leakage, was largely tamed.

The blue seat was highlighted with red pinstriping and special graphics

The modest dry weight of 177 kg was also around 45 kg lighter than comparable Japanese 750s at the time. But reliance on the US market saw Triumph caught out by a falling dollar after retail prices were already established and cash flow remained a serious concern. By 1977 Meriden needed a quick lifesaver and the Bonneville Silver Jubilee was just the ticket.

Basically, the Triumph Bonneville Silver Jubilee was a standard 750 Bonneville, sharing the venerable long stroke (74 x 82 mm) 744 cc 360-degree parallel twin. With a mild 7.9:1 compression ratio, and fed by a pair of small 30 mm Amal carbs, the engine produced a very modest 44 horsepower at 7000 rpm.

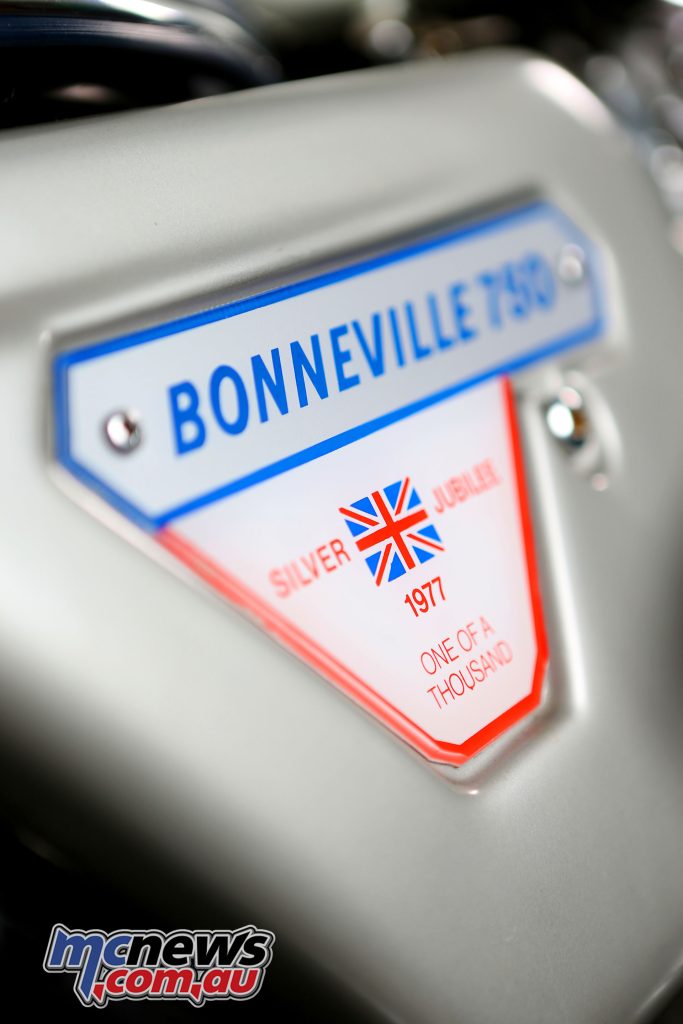

What set the Jubilee apart were the gaudy details, including shiny chrome-plated engine covers, fork covers and taillight bracket. Blue and red striping highlighted the rather undistinguished silver paint, striping accents continuing on the 19 and 18-inch wheel rims and special Dunlop K91 “Red Arrow” tyres.

The Jubilee’s most unusual styling feature was the blue seat with red piping. Even the silver chain guard received the royal treatment, accented in three colours. The hand-welded frame was the often criticised and controversial “oil-in-the-frame” type first introduced with the T120 in 1971.

But by 1977 it was well developed, with shorter shocks to lower the initially intimidating seat height. For the Jubilee Triumph introduced a pair of Girling gas-filled upside-down shocks, with the spring pre-load at the top, these soon making their way to the rest of the Bonneville range. US examples received the smaller, traditional “teardrop” style fuel tank, with UK and export versions the less attractive ‘breadbin’ style.

Initially it was envisaged that only 1000 Jubilees would be built, hence every machine carried the proud boast of “One in a Thousand.” However, demand persisted so Meriden produced another 1000 and finally a further 400 for general export.

For these final examples Triumph replaced the emblem with “Limited Edition.” Obviously “One in about Two and Half Thousand” didn’t have quite the same ring. One thousand were destined for the US but they sold very slowly as Americans couldn’t really identify with the Royal event.

Even in America the extravagant looks were considered over the top, and Jubilees sat in US showrooms gathering dust well into the 1980s. Elsewhere they were immediately considered investments and many were squirrelled away with little or no miles put on them.

As a Meriden spokesman said later, “They were brilliant. 50 per cent of owners put them away and never ran them so the warranty call back was minimal!”

Five things about the Meriden Workers Cooperative

- As a Labour government was elected in February 1974, this resulted in more government sympathy for the workers and Secretary of State Tony Benn encouraged the workers’ co-operative.

- In August 1974 Tony Benn visited the freshly-painted Meriden factory and after speaking to the workers on the Government’s industrial policy departed to the strains of “For he’s a jolly good fellow…”

- Despite government support Norton Villiers Triumph refused to sanction the Meriden co-operative agreement. In November 1974 formal redundancy notices were served on Meriden’s 879 co-operative workers and they re-imposed the blockade.

- The Meriden Co-operative was eventually ratified in March 1975, the blockage formally ending the same day. With government support withdrawn Norton Villiers Triumph was placed in receivership in October 1975, and the following year the Co-op managed to secure the Triumph name and worldwide distribution rights.

- A continual decline in profitability saw the workforce diminish to 450 by 1980. In August 1983 Triumph motorcycles went into voluntary liquidation and the Meriden factory demolished to make way for a residential development.