Turning a four into a twin, corner by corner – With Mark Bracks and Trevor Hedge

The days of a traditional engine tuner getting the most performance out of an engine by changing jets, altering camshaft profiles or doing a bit of piston work are long gone.

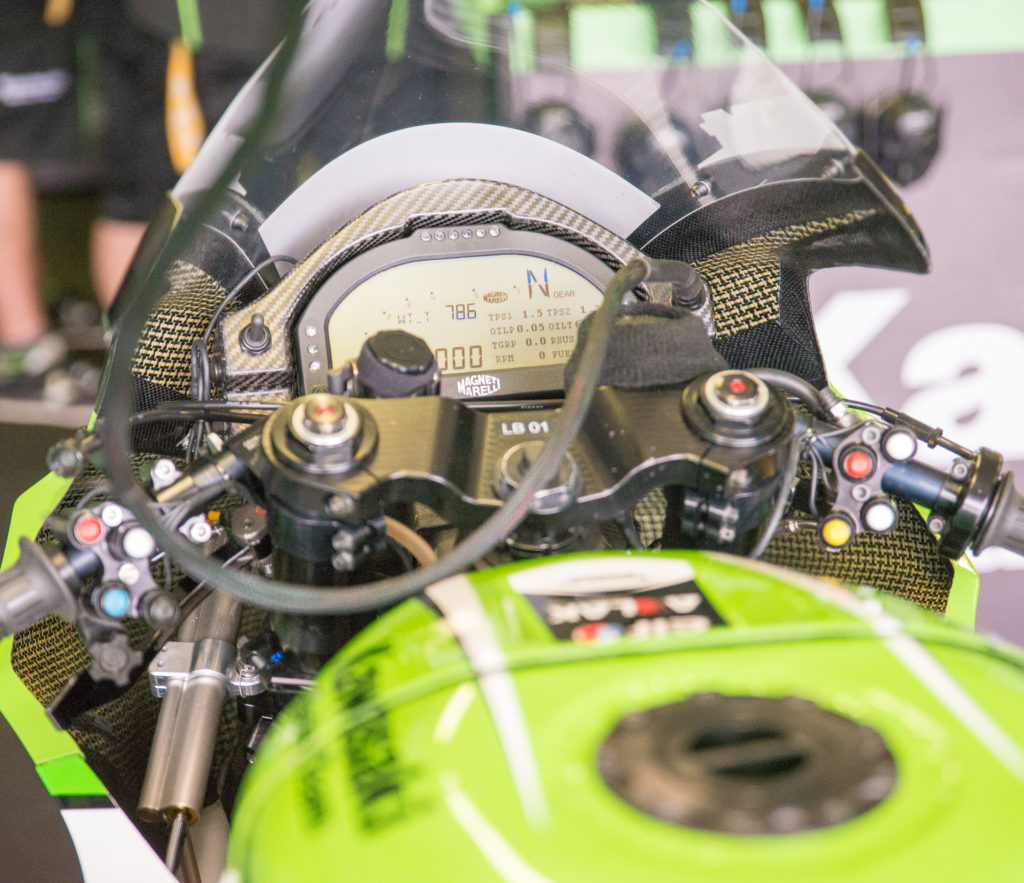

If there was any doubt of this, and the magnitude of responsibility that electronics plays in success in World Superbike Championship racing, it was confirmed at Phillip Island at the dawn of the 2014 Superbike World Championship. The results spoke for themselves as if you don’t have the latest software in the ECU, you are toast.

For all teams electronic upgrades were the major focus of off season development.

This is no more evident than the resurgence of the Suzuki GSX-R1000 with the Voltcom Crescent team and the initial competitiveness of the Pata Ten Kate Honda Team.

The Gixxer and Fireblade have, basically, been the same bike for the best part of a decade with no revolutionary changes to a successful formula. Add in state-of-the-art Motec and Cosworth software to the ECU, respectfully, and they are completely different beasts, particularly the Suzuki.

Interestingly, to be at the front of the pack is not solely the case of fitting upgraded software and “bob’s-your-uncle.” It is more vital to have an extremely talented telemetry boffin in your corner to be able to decipher as it is to have an exceptional rider in the saddle.

It is no coincidence that the change in performance of both Suzuki and Honda can be put down to new team employees to get the most out of the software. Pata Honda has signed ex-BMW and Aprilia man, Massimo Neri while the Voltcom Crescent Suzuki team has signed Davide Gentile who has also worked with BMW and Yamaha. Both are rated as legends in the paddock.

Maybe Suzuki already has caught up as new signing, Eugene Laverty rode an inspired race to charge back from fifth in a ultra determined ride to win the opening race of the year by a healthy margin.

In race two, he was well on the way for a repeat, but his engine lunched itself and forced the end of the race. After that smoke screen at Siberia, maybe the Suzuki electronics still need a bit of fine-tuning!

Impressively, the Honda’s were a lot closer to the front with a fit Jonathan Rea and Leon Haslam within a couple of tenths of the fastest bikes, the pair a lot more relaxed and upbeat than at the corresponding event in 2013.

The first step of giant strides have been taken to lessen the gap over a race distance to both the Aprilia and Kawasaki while Ducati appears to be on the way back with Chaz Davies claiming the new lap record that will stand for a few years with the “Evo” specification bikes taking over next year.

Conversely for Ducati, Phillip Island was the scene of its solitary success in 2013 when retired champion, Carlos Checa was fastest during the test and put the bike on pole position.

As in modern bike design, there is very little in separation of these electronic performance enhancements, so it all depends on how you can tune a raft of variables to maximise performance and how well you can get the power to the ground at the end of the race as at the beginning of it.

As such, many of the systems are mirroring each other in monitoring machine dynamics but it is the application of the electronic packages that is now playing a massive role in who steps on the podium.

One common denominator when trying to extract information from these guys was three words; big bang engine.

Now, “Big Bang” engines are not allowed in the WSBK because rules state that you must race what is homologated for the street, and all of the current Japanese competitors run in-line four-cylinder “screamer” engines in their production models. (The Yamaha YZF-R1 does run, what they market as, a cross-plane crankshaft but ironically, they withdrew from the Superbike World Championship a few years ago).

It would’ve been easier to detect Lasseter’s Reef under the black top of Phillip Island than to extract any information about how “big bang” dynamics are achieved in a “Screamer” engine, but rest assured it is being done and it is all down the the electronics.

It all stems from the Ride By Wire (RBW) technology; cutting ignition to cylinders through certain sections of track, effectively turning the four-cylinder engines into twin-cylinder engines at points on the circuit where the four-cylinder machines struggle for drive if firing on all cylinders.

Thus, via electronics, the latest technology allows the four-cylinder engines to also combine the best traits of the twin-cylinder engines where required at certain parts of the track.

Programming all those parameters is enough to make your head spin… Which is why so much manpower is invested on a race weekend in studying data traces to try and find every tiny fraction of performance improvement via the engine management systems; tailoring the engine response from one corner to the next throughout the lap, and then also factoring in tyre wear over race distance….

Bit different to turning up to the track with a box of different jets or changing the cam timing….