Phil Hall takes a look at the Yamaha XZ550

Orphans Pt2

While it is generally considered that the Americans invented the concept that, “If some is good, more is better” it was slavishly followed by the Japanese motorcycle manufacturers during the 1970’s-80’s. All of the big four manufacturers competed with each other to plug every possible gap in the marketplace. They produced bikes from 50cc to 1000cc and often even doubled up in capacity classes for incomprehensible reasons. Honda, for example, produced several different road bikes in the 350cc class, the CL being a forerunner of the adventure/road/trail genre, the 350 twin being a commuter bike and the 350/4 being the sports variant.

It was clear that they were determined that, no matter what type of bike you wanted and what capacity of engine was required, they would have you covered.

And this is just road bikes we are discussing here. The burgeoning off-road category saw the Japanese factories producing a bewildering array of models there, too. Indeed, such was the degree of “monkey see – monkey do” that you could be sure that, if you wanted a small capacity observed trials bike, for example, you would have your choice in the same way as if you were looking for a commuter bike, a sports bike, a touring bike or whatever. As my brother so eloquently puts it, “If one of them sneezed, they all caught cold.”

Some bikes arrived on the market fulfilling no seemingly valid need at all and so we had four turbocharged bikes briefly competing with each other over who could provide the most throttle lag. In a “well, it seemed like a good idea at the time” scenario, all four R&D teams decided that a medium capacity engine, boosted by a turbocharger, could provide equal performance with a large-capacity bike.

And so it could, but with some caveats. While turbocharging of the day worked well when a constant throttle opening was required, in the real world of constant on-throttle, off-throttle usage, it didn’t. In fact, even with the addition of waste gate technology, recent turbocharged cars still suffer slightly from turbo lag, some worse than others, though not nearly to the same extent as early examples did. It wasn’t really useful to have the engine arriving at full boost when the throttle had already been closed for the next corner.

The added weight that was part and parcel of turbocharging meant that the normal medium sized bike actually became quite a heavy bike. The requirement to dissipate copious amounts of heat added weight and complexity. And, until the boost kicked in, the bike was slower and more sluggish than its non-turbo’ed brother.

Worst of all, a normally aspirated 1000 was still quicker and easier to live with and so it wasn’t surprising when the turbo bubble burst, pretty soon as soon as it was inflated. Much the same could be said for rotary engine bikes, anti-dive braking devices of various kinds and the 16” front wheel fad which worked fine on the race track but not on real-world roads of indifferent surfaces.

And so we come to another “orphan” bike. As noted before, not really an orphan since we know who its parents were, but more an abandoned child whose parents disavowed it whilst it was still in its infancy.

I speak of the 1982-3 model Yamaha XZ550.

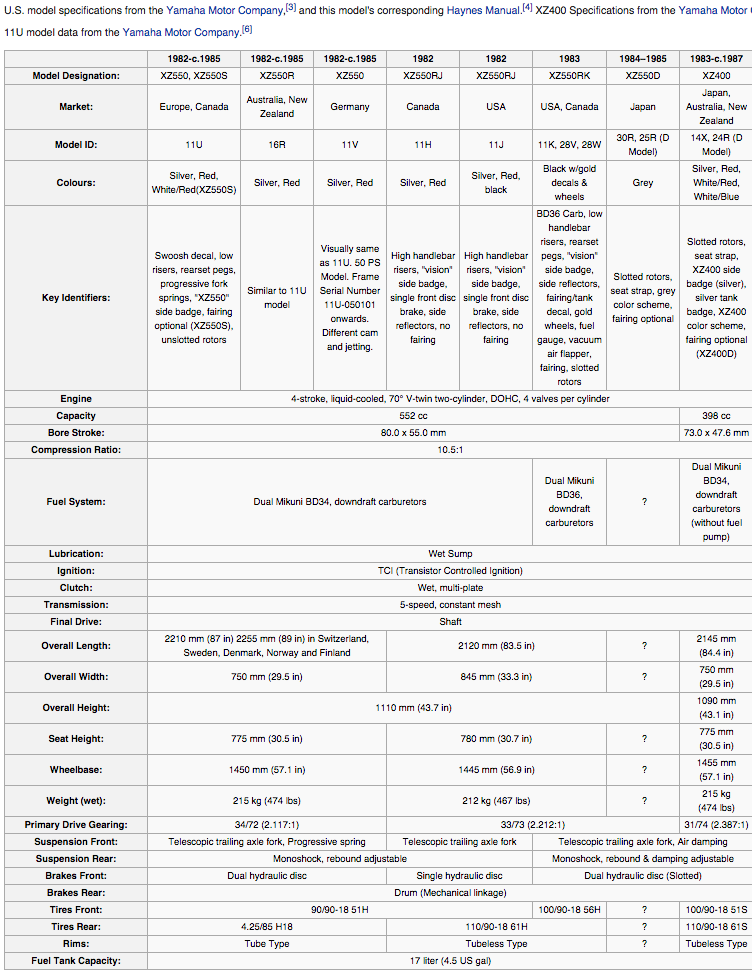

In an attempt to plug every market gap and whizz-bang the other manufacturers with new and exciting technology, Yamaha introduced the XZ in 1982. It was a very advanced design. The V-Twin engine was mounted longitudinally, Ducati-style (Honda’s CX500 had the cylinders mounted transversely, Guzzi-style – we must be different). The engine was very oversquare (bore much bigger than the stroke) which hinted at performance aspirations. And it was quite quick for its meagre capacity. It revved to over 10,000RPM but had a surprising and impressive spread of torque as well. It also was one of the first Japanese bikes to feature liquid cooling (The CX500 had scooped it here too) which meant it was less prone to long-term overheating, had more long-lasting engine components and was much quieter in operation. While other manufacturers retained vestigial fins so as not to frighten the traditionalists too much, Yamaha did away with them altogether which means the 1982 engine still appears surprisingly modern.

Known as the XZ model in most markets, the marketing gurus continued with their obsession of naming their bikes with silly names for the USA market where it was badged as the “Vision.” On reflection, it wasn’t such as bad idea. The bike DID represent Yamaha’s vision for the future and it is pure speculation of course, but one wonders just where Yamaha would have gone from there had the model been a raging success.

The XZ was the first Japanese machine to break away from the traditional “sidedraft” carburetion system, featuring instead, two downdraft carburettors feeding its DOHC 4 valves per cylinder head. This arrangement is de rigueur these days but was quite revolutionary then. Having the airbox on top of the engine feeding cold air to the carbs necessitated some changes in fuel tank design with a what then seemed huge hump of a tank to make the necessary room. Despite its large size, the tank only held 17 litres due to constraints of the air cleaner.

And it was the carburetion that was to prove to be the Achilles heel of the model. No matter what tuning “wheezes” were applied, the XZ suffered from an off-idle flat spot that marred smooth acceleration and annoyed the daylights out of owners, mechanics and dealers. It became so synonymous with the model that it was nicknamed “The Vision Stumble”. Despite all manner of fanciful “fixes” the flat spot problem got around the traps like wildfire and probably contributed significantly to the bike’s early demise. Reading up on what caused it and how it could be fixed is like reading a whodunit. I remember how tainted the model became and how quickly it happened so well.

There were some other issues as well. In an effort to accommodate a relatively long engine while not making the wheelbase too long itself, Yamaha had the front axle carried in fork clamps that had a significant offset. While it achieved that end, it impacted upon handling, making the bike overly “twitchy” at the front end. The “fix” was to fit a slightly larger than stock front tyre (questions were asked as to why owners had to find a “fix” for a brand new bike). Electrical problems allied to the charging system stator and to the electric starter soon became apparent also and sales slowed to a crawl.

Yet there were more issues. The price you pay for complexity and innovation is high and the XZ was quite a deal dearer than other 550cc offerings, not only from Yamaha but from their rivals as well. And then there was the styling. In the USA, the target market, the bike was seen to be ugly (no doubt Yamaha thought they were doing the right thing in a market dominated by naked longitudinally-disposed V twins) Though it was available with a full fairing from the outset, buying it with the fairing made the bike even dearer so it was only an option.

In an attempt to stop the rot (having solved the “stumble” by redesigning the carburetion) Yamaha made the 1983 model available with the fairing and pitched it more at the middleweight touring market. There is no doubt that the bike looks better with the fairing, but I liked it just as much without. But the damage had been done. Nothing sticks worse than a reputation for unreliability and bike buyers are a discerning lot. Price increased (of course) and the model was quietly discontinued at the end of the year amidst flagging motorcycle sales across the board and the Japanese manufacturers, always canny when reading the writing on the wall, saw that rationalising the catalogue made more sense. Better to do a smaller number of things really well than try and be all things to all men.

Today the XZ is one of the many forgotten models from the golden era of Japanese excess. Loved by its adherents it is regarded as a cult bike and a missed opportunity. Mention it in a pub discussion and most will say, “The WHAT?”

Which is a shame because, for all of its faults, it was an innovative bike and it really deserved a better fate.]